"The inferno is not down below; it is here, ever-present…"

10 March 2014

Magazine C&

6 min read

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work? Aïda Muluneh: I don’t remember exactly when but it was a few years ago that Simon Njami mentioned to me that he was planning a show based …

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work?

Aïda Muluneh: I don’t remember exactly when but it was a few years ago that Simon Njami mentioned to me that he was planning a show based on the Divine Comedy. Initially he told me to work on a collection based on paradise but eventually, I guess to provoke me in my creative process and knowing my personal life all too well, I was assigned with inferno. Coming from a place like Ethiopia, where religion is a way of life and a culture for us, it was interesting for me to see church paintings that depicted “hell”. Hence, since the exhibition is based on Dante’s body of work, it was relevant to understand his work in order to draw inspiration for how I perceived the inferno.

MMK/C&:In its merging of Christian beliefs and moral values as well as classical pagan topics, the “Divine Comedy” represents a deeply-rooted Eurocentric concept of society, values and culture. The exhibition aims at dismantling the European prerogative of interpretation and looking at it from a new angle. To what extent do you think this approach can lead to the Eurocentric interpretational sovereignty being generally put into question?

AM: For me personally, it wasn’t necessarily looking at the Divine Comedy in the context of a Eurocentric concept, being raised within the Ethiopian Orthodox church, this wasn’t something extremely foreign to me. In all honesty, while creating the collection, I wasn’t necessarily thinking about Eurocentric ideologies. For me it was about trying to explore the notion of the inferno as it relates to my background and not necessarily politicizing or over-intellectualizing what I was producing, but rather trying to express things of the past and present.

MMK/C&: In European-North-American art history, the “Divine Comedy” has been interpreted by numerous artists (such as Botticelli, Delacroix, Blake, Rodin, Dalí or Robert Rauschenberg) – what role did this play for you in respect to your engagement with the topic?

AM: I did some research trying to draw some inspiration, I even found an old film based on the inferno but soon realized I had to find my own personal way of relating to the work. I chose to focus on Canto 20, which had the story of the backward turned heads of Amphiaraus, Tiresias, Aruns and Manto. There was something compelling about this, never being able to see what is ahead but always looking backwards.

MMK/C&: How do religion and ethics feature in your artistic practice? And consequently, what do the terms heaven/hell/purgatory mean to you personally?

AM: In my photography, my main focus is obviously to document what I find interesting, and in my fine art photography, I find myself always drawn towards my personal experience of growing up like a nomad and seeing many different cultures. It’s not necessarily religion or ethics but more dealing with emotions, struggles, life, love, loss and so forth. Hence, when I think about heaven and hell, they are not something that is in another world but rather ever-present in this world, we don’t need to die to find them.

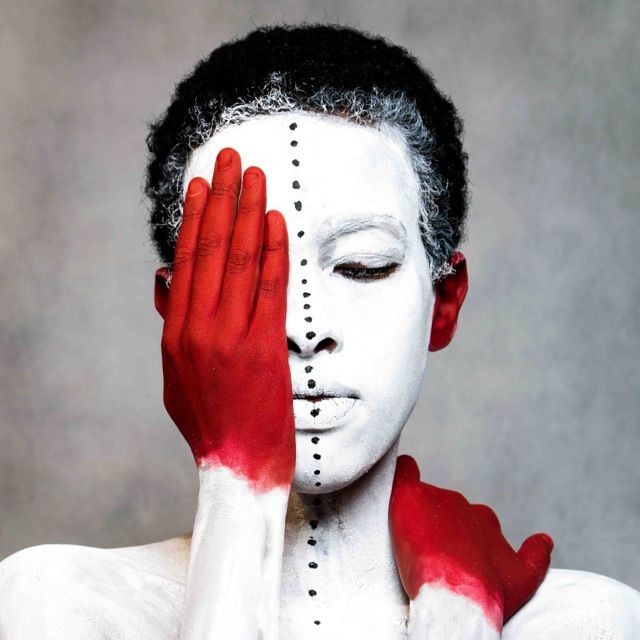

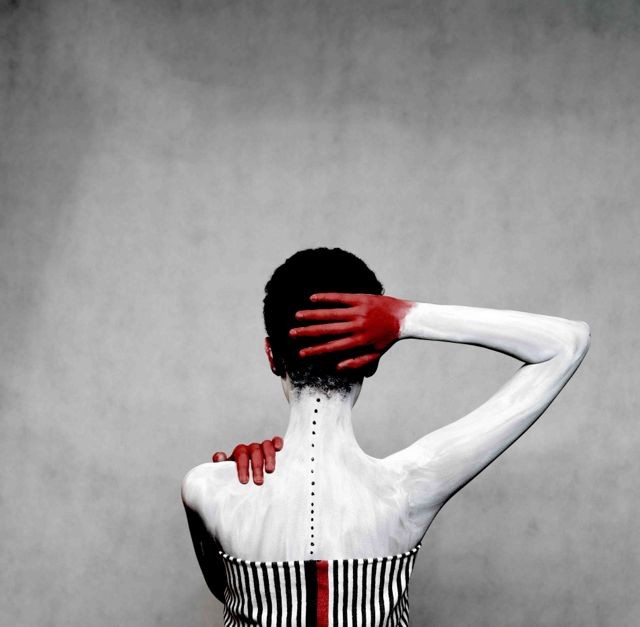

Aïda Muluneh, 99 Series, 2013 Series of seven photographs Photo paper 89 x 89 cm each. Courtesy of the artist

MMK/C&: The over 50 art pieces in the exhibition are assigned to the areas heaven, hell and purgatory. What realm of the afterlife does your work belong in? How did this allocation come about?

AM: As stated above, my work is part of inferno.

MMK/C&: What is the work exhibited at the MMK about?

AM: This is the text I submitted as it relates to the work:

“Inferno is made of history, not only of a country but of self, of exile, of bloodshed, of loss, of mourning, of bitterness, of broken hearts and broken wings. The inferno is not down below; it is here, ever-present, next to us, in our memories and in our minds. It is made of delusions, of prostration, of hiding behind masks to validate our existence and hidden agendas; it’s a mask we wear to fool ourselves and others in an attempt to get ahead, yet we are void in our survival. We live in the gray cold existence, uncomfortable like the dirty snow of western winters or like the polluted skyline of what we call Ethiopian modernity. Pulled between the past, the present and the future, we wrap ourselves with forgotten heritage and dream of looking towards the future, but we are stuck looking into the past. For eternity we are toiling with rituals and ceremony, yet our past deeds are marked by unhealing wounds, the blood of false victory stitched by the threads of nostalgia. A story we each carry, of loss, of oppressors, of victims, of disconnection, of belonging, of longing to see paradise in the dark abyss of eternity.”

MMK/ C&:(If it was commissioned:) How did you go about the creative process?

AM: I initially started with one body of work to see how I can formulate the collection. The process of finding body paint in Addis Ababa was a great challenge and in fact, together with the first model, Selam Berhane, we had the great idea of making our own body paint for the shoot. It didn’t go so well but it strengthened the direction that I wanted to head towards and gave me great inspiration. Eventually, I managed to buy some body paint in the USA and came back with it to Addis Ababa. The new model, Salem Nega, who was four months pregnant at the time, generously agreed to the long process. It wasn’t until the images were photoshopped that I realized it was the darkest work that I have ever produced. It has an eerie feel to it, kind of like a car accident that you just can’t turn away from but rather become more curious about. The colors worked well and the red hands played a central part in the full collection.

The exhibition The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Hell, Purgatory revisited by Contemporary African Artists curated bySimon Njami,MMK / Museum für Moderne Kunst, 21 March - 27 July 2014, Frankfurt/Main.

from

Aïda Muluneh

What Are the Stakes of Representing Art from Africa in Dubai?

Learning from Addis Ababa

7th Print Issue is Out Now!

from

Simon Njami

Illa Donwahi: Enabling Art in Challenging Environments

Africa Remix