The Desire to No Longer Be Silent

Multimedia artist Kemang Wa Lehulere talks to C& about the artist Gladys Mgudlandlu, the notion of displacement, and the excavation of hidden works played out in his new show, Bird Song, currently on view at Deutsche Bank KunstHalle in Berlin. C&: Going down memory lane, the first time we met was in 2008 at the …

Multimedia artist Kemang Wa Lehulere talks to C& about the artist Gladys Mgudlandlu, the notion of displacement, and the excavation of hidden works played out in his new show,Bird Song, currently on view at Deutsche Bank KunstHalle in Berlin.

C&: Going down memory lane, the first time we met was in 2008 at the festival Performing South Africa at HAU here in Berlin. You were involved with the artist collectiveGugulective. Fast forward, almost ten years later, how does it feel to be back in Berlin with a major solo show?

Kemang Wa Lehulere: It is exciting. Berlin is my favorite city in Europe even though I have never lived here. It is related to the fact that I came with Gugulective to be part of the event you mentioned. It was the first project I ever did outside of South Africa. At the same time, displacement has also been an essential element in my work; South African history in relation to German history; and what is happening in the world right now.

C&: So in which way is displacement a crucial element in your practice?

KWL: This show is called Bird Song which is directly related to the artist Gladys Mgudlandlu. I am exploring her artistic practice and the way she worked in the sixties and seventies as a Black South African woman during apartheid. Gladys Mgudlandlu explored issues of land, displacement, ideas around home, and what that means in its multiple forms.

The year 2013 marked the centenary of the Natives Land Act in South Africa. In 1913, Black South Africans were officially and legally dispossessed from their own land. When apartheid began, this act of land dispossession became more brutalized. Nowadays there is more than ever an acute consciousness around land politics in South Africa, especially sparked by the student protest movement that started in the spring of 2015 with Rhodes Must Fall protests.

.

<figcaption> Kemang Wa Lehulere, My Apologies to Time, 2017. Installation, measures vary. © Kemang Wa Lehulere, courtesy STEVENSON Cape Town and Johannesburg

.

C&: What do you think of this whole idea revolving around decolonizing knowledge?

KWL:Decolonizing is basically about dismantling this system of power. One piece at a time. I believe the education system is the most important aspect to begin with because it is where people are shaped. At the moment and for a long time the educational system has not produced people that think critically, but rather people who fit in the system. There is a new generation of people acting against this, coming from the Black consciousness movement or Pan-Africanism. There is a resurgence of political philosophy that aims to break down the system, including the education system. Not only is it about changing the curriculum, but also about accessibility to that educational space. This is something I have always been concerned with. For instance, I could not afford to go to university. As a result, I had to do projects here and there in order to get the funds for my studies. And this took away the time I needed to study.

To bring it back to the show here, the materials I worked with are old school desks. I have always been interested in pedagogy. In school I complained to my English teacher because the curriculum was concerned only with English and American perspectives. This same teacher developed a special curriculum outside of the official one for me and a friend of mine. So, while she showed us carefully selected books by writers from African contexts, we would sit and discuss this material during lunchtime. At the end of the day you have to ask yourself where you fit into the normative body of knowledge, then to demand visibility, and at the same time to dismantle symbols of power in how they remain colonial and carry Western white patriarchal elements.

C&: So for this show Bird Song in Berlin you used deconstructed school desks. What does the idea of installation mean to you? Why did you choose this format, these materials, jazz music and other media?

KWL: I always try to search for the materials first. For me it is like a journey. It has been only two years that I have been working with the materials the way I do now. In the beginning it was wood and then the metal components of the desk came in. Aside from that I am currently developing pieces that can be mobile. They would operate as sculptures within performances. In addition, the exhibition catalogue includes a pamphlet as a supplement, i.e. a publication in a publication. It is a correspondence with an architect I have been working with. This is going to be the second edition of the pamphlet series. I also had the idea of including some jazz music in the show that a friend of mine, a jazz musician, composed specifically for this project.

.

<figcaption> Kemang Wa Lehulere, The Bird Lady in Nine Layers of Time, 2015. Documentation (Reconstruction of wall painting in the former house of Gladys Mgudlandlu in Gugulethu). Digital video, video still. © Kemang Wa Lehulere, courtesy STEVENSON Cape Town and Johannesburg

.

C&: Why did you choose to engage with Gladys Mgudlandlu's legacy?

KWL: In 2014 I was having dinner with my aunt Sophia when this neighbor came by and gave me a book about Gladys Mgudlandlu. In the past, we had often gone to Gladys' house where she painted on the walls and the ceiling. I have been making murals with chalk as well. So I went to the house to see if the murals were still there, only to find out they weren't. I then became curious and decided to start something with this. My aunt kept telling me that she saw those murals in 1971/73. I was not sure this was true because in the seventies she had had an extremely traumatic experience during the Soweto Uprising in 1976. She started to remember that there had been a rural landscape and slowly built up a whole picture. So I went to this house that Gladys owned, measured the living room and rebuilt it in my studio. To test her memory, I interviewed and invited my aunt to reconstruct those murals on the black walls I provided. I made a video of this process. Those works are titled Those Murals Have a Memory. She remembered the elements bit by bit, first the colors and then the landscapes. Around that same time, I was able to acquire some works by Gladys at an auction. I really thought I would have to focus only on those paintings and my aunt's recollections. But one day while working on the wall at Gladys' house, we discovered the image of a bird. That was incredible.

When I was looking at Gladys’ works, I saw this strong sense of landscape, the birds and flowers. After the land question was very much apparent from 2013 on, I started to read her work with this backdrop in mind, realizing how extremely radical her work was. On the whole, she was commenting on land dispossession. Like my family, Gladys had personally experienced the forced removal. We were all sent to the township in Cape Town, Gugulethu.

.

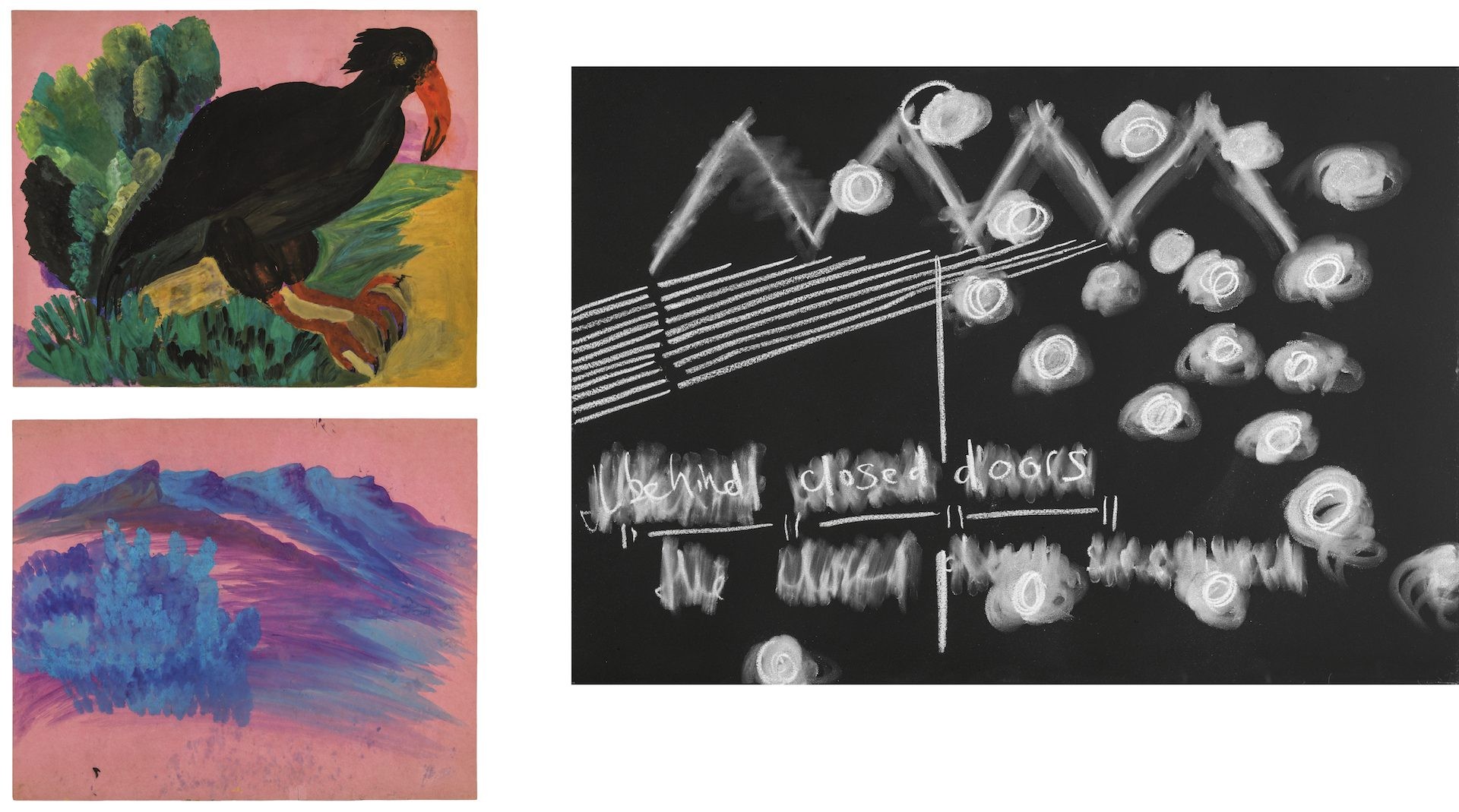

<figcaption> Kemang Wa Lehulere, Does this Mirror Have a Memory 4, 2015. Left: Gladys Mgudlandlu, untitled, 1966,

gouache on paper, right: Drawing in collaboration with Sophia Lehulere, 2015, chalk on blackboard. © Kemang Wa Lehulere, Sophia Lehulere, Gladys Mgudlandlu, courtesy STEVENSON Cape Town and Johannesburg

.

C&: What did you feel when digging into this long buried past?

KWL: It was almost unbelievable, I had the feeling I was in trance. It would be nice to educate people in the neighborhood, to inspire them to do similar things and to have an exhibition space. Since I discovered the murals, I have been trying to turn her house into a museum. It is a long-term venture I am slowly working on, starting with building a library.

C&: And why are you creating a library?

KWL: To come back to the issue of education, with the collective Gugulective we always wanted to have our own school as well as our own library where we would develop our curriculum. After discovering the murals, I wanted to develop something organically, hence a library made sense. The library I am designing could also function as a mobile one that I could move to different spaces. Next month I am launching the library along with a lecture called Decolonizing the Sky with an astrophysicist, who is going to talk about African cosmology.

.

<figcaption> Kemang Wa Lehulere in his studio,Cape Town 2016. © Paul Samuels

.

C&: You said earlier that you spoke to your aunt and how she was traumatized in the seventies. How did you experience her telling of the stories? How did she feel about talking about it?

KWL: Before and during the interviews, my aunt made very clear that we would not talk about the specific time and context of 1976 when the Soweto Uprising occurred. That is what made me interested in the silence of history as we could not speak about 1976 at home. For instance, we were not allowed to say the word “police” at home when my aunt was around. However, this history was also missing at school. It was another form of silencing that was strongly present.

C&: As you described these situations, it feels as if the silence at home was a form of self-protection because the events were too hard to cope with. On the other hand, the silencing in the outside world resulted from a system of oppression.

KWL: It is something I have been thinking through and working around for a long time. It makes me think of the bird that Gladys painted in the house, which was just really incredible. To me, this bird symbolizes many things in an individual and collective sense. I believe birds stand for freedom and the desire to no longer be silent.

.

Kemang Wa Lehulere, Bird Song, March 24 - June 18, 2017, Deutsche Bank KunstHalle in Berlin.

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas