The British War on Yoruba Spiritualism

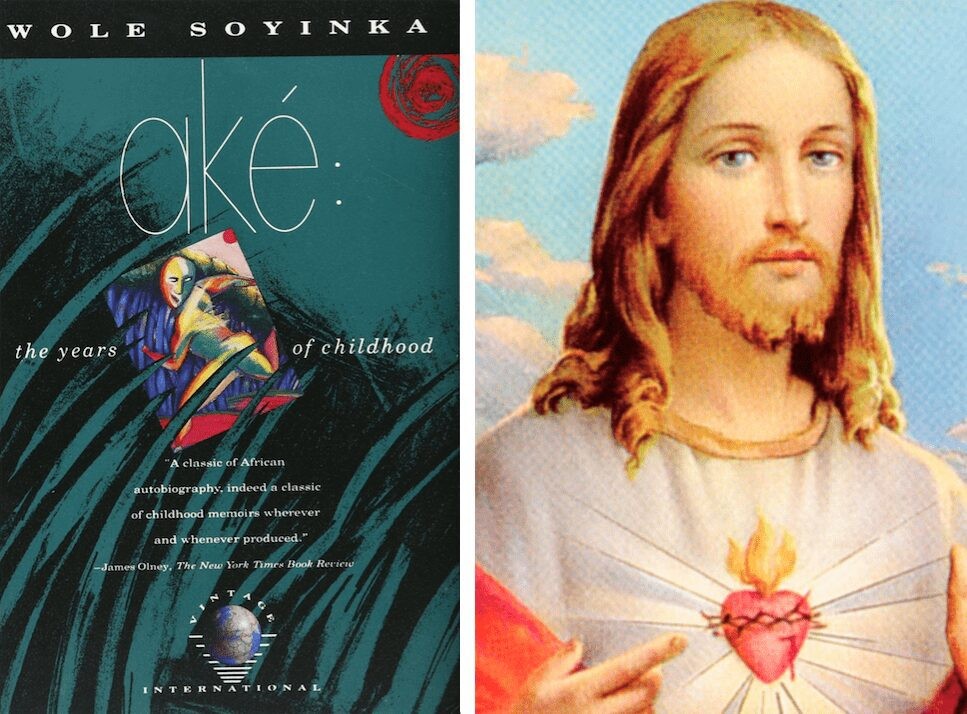

The nuances surrounding the way in which Wole Soyinka refers to religion in imperial Nigeria in his memoir, Ake: The Years of Childhood are evocative of those I experienced growing up in post-colonial Britain two generations later. The concept of “home” is brought into question and we must ask if the eradication of Yoruba spiritualism …

The nuances surrounding the way in which Wole Soyinka refers to religion in imperial Nigeria in his memoir, Ake: The Years of Childhood are evocative of those I experienced growing up in post-colonial Britain two generations later. The concept of “home” is brought into question and we must ask if the eradication of Yoruba spiritualism is responsible for the lack of ancestral connection felt by those of Yoruba heritage long after the regime’s collapse.

Aké: The Years of Childhood tells the story of Wole Soyinka’s boyhood between the mid-1930s and the early 1940s, the final chapters of British imperialism. His critique of the injection of European colonial mentalities into Nigeria is subtle yet incredibly thorough as he recalls the observant tendencies of a child to invoke the impact colonialism had both on himself and his environment via the discussion of religion. While Soyinka often questioned religion in mid-20th century Nigeria, I did the same for Britain in the early 21st century. Blonde Jesus made sense in the UK, where I was born and raised by my Nigerian-born parents. But during childhood summers in Lagos, a hyper-Western Christ encouraged scepticism. Why was the iconography of the pervading religion physically so utterly unrepresentative of my family, the congregation and myself? I began to wonder if this could really be the Nigerian religion. One explicit link between Soyinka’s Nigerian and my British childhood is that colonialism meant supremacy.

Yoruba dancer 2017. Photo: Hizick27

Ilé-Ifè, the cultural and spiritual Yoruba capital, was settled in 400 BC. In the centuries to come, Yorubaland the precursor to Nigeria, Togo and Benin would become one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s most artistically rich and complex cultures, with Yoruba art often paying homage to a plethora of deities. The selective imperial amnesia of post-colonial Britain meant that the first time I witnessed the fruits of this era was in 2010 at the British Museum’s exhibition, Kingdom of Ife: Sculptures from West Africa. The destruction of Yoruba history is part of the larger legacy of cultural whitewashing and religious abrogation, making one feel displaced. I felt this at the exhibition, and Soyinka felt similarly during an upbringing at the hands of a traditionally spiritual grandfather, an Anglican minister father and a mother whom he dubbed “Wild Christian”. In reference to the Yoruba experience Soyinka said, “All experiences flow into one another”.

Aké recounts a still-colonised Nigeria, a “country” much older than Soyinka’s parents, whereas I navigated the ins and outs of a second-generation upbringing in the country responsible for – at the height of the regime between 1914 and 1923 – holding sway over 458 million people, a quarter of the world’s population. Spiritual connection strengthens an idea of ‘home,’ and longing for this feeling is lonely and tiresome. Our mutual experience of not knowing how to relate to messy, forced Euro-Yoruba childhoods can be argued as being one of the many things Soyinka was referring to in his aforementioned quote.

British colonialism blossomed under the lazy guise of an anti-slave trade initiative, steadily pillaging the fertile Nigerian land and laying waste to the people’s beliefs. As is discussed by Deidre Coleman in Romantic Colonization and British Anti-Slavery (2005), the growing global rejection of slavery instigated a search for a system in which the West could continue to profit from the fruits of the African and Asian continent through “influence” and mission rather than the blatant enslavement of people.

Christianity and Yoruba religion are far from congruent, but the four-year-old Wole had no choice but to allow a concurrent existence. With a hopeful amalgamation of his grandfather’s spiritual teachings and those of the Wild Christian, Wole-the-Boy was able to make sense of the two. Could the illness of Christian colonists be explained by witchcraft? This dichotomy is alluded to on page 32 of his memoir. Wole and a friend observe the stained glass windows in St. Peters Church depicting saintly white figures wearingegúngún masquerading dresses, yet with uncovered faces. Naturally, confusion was inspired.

“They are not egúngún’ she said, ‘those are pictures of two missionaries and one of St Peter himself.”

“Then why are they wearing dresses like egúngún?”

“They are Christians, not masqueraders. Just let Mama hear you.”

Early on in the text, Soyinka cleverly subverts one of the Bible’s most retold allegories to explain colonial indoctrination. A pomegranate takes on the role of the apple, representing the plastering of European beliefs over a generations old spiritual school of thought. Nigeria takes on the role of Eden. “The pomegranate was foreign to the black man’s soil, but some previous bishop, a white man had brought the seeds and planted them in the orchard… Before the advent of the pomegranate it had assumed the identity of the apple that undid the naked pair.” Soyinka goes on to insinuate that the “pomegranate” is responsible for the downfall of Aké, in fact the collateral damage caused by said “pomegranate” is the reason why the Yoruba religion remains a myth to people like myself, ethnically Yoruba but legally a Western millennial, referring both to the fact that it is no longer part of our oral tradition and that it is shrouded in mystery and magical ritual.

Centro Habana Santeria. Photo: Bernardo Capellini

Modern interpretations of Yoruba faith as for example Santería (Spanish Catholicism meets Yoruba religion) are seldom practiced outside of the Caribbean, and so were lost on me, a British-Nigerian.In an interview with Vogue, one half of the French-Cuban twin sisters and singers Ibeyi insisted, “When you sing these songs, you hear the thousands of women who sang them before you”. She referred to a Yoruba chant they sang in May 2016 for the opening of the Chanel fashion show in their childhood hometown of Havana. This spiritual link bridges the gap between the no man’s land one finds oneself in as a second-generation immigrant – and how I wish this bridge was also built between modern Yorubaland and Europe. If one has no means of hearing the singing women, is it still possible to identify wholly with the culture of one’s ancestors?

Nigeria’s lingua franca, Pidgin English has become its own language. With an estimated 20 million speakers, it would be unfair to say that language is the most recognizable colonial souvenir, but in the case of religion, Nigeria is unrecognizable. To argue that colonialism took away from the ancestral idea of core “Yorubaness” would be entirely fair. 51.9% of the country’s citizens identify as belonging to one of the many schools of Christianity, with a measly 0.8% identifying as “other”. “If we do not tame religion in Nigeria, it will kill us,” Soyinka lamented in Abuja last January. A millennial translation could be the ever-trending call to “decolonize the mind”.

Times critic John Leonard described the author as a child who grew up “…in a garden of too many cultures,” giving reason to Soyinka’s melancholy. Now Soyinka speaks with the bitterness of a stateless man who saw the heart of his culture forgotten. Personally speaking, feeling neither a deep connection to my ancestral culture nor to that of England, leads me to conclude that such a complex childhood in this multifaceted garden can only engender an adult who knows no home. But then again, what is “home”?

Olamiju Fajemisin is a British-Nigerian freelance writer based in Berlin. Her work focuses on art, music and contemporary culture with an emphasis on race.

C& Center of Unfinished Business is on show until 30 June 2018 in the foyer of Akademie der Künste, Pariser Platz, Berlin

Identity

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

In Conversation with Lubaina Himid: The Artist Set to Represent the UK at Venice Biennale 2026

, so I dream: An Ode to Stuart Hall

Nigeria

‘To Treat Process with Care and Intention’: Favour Ritaro Carries Forward Important Curatorial Legacies

ART X Lagos 2024 Reveals Theme, Gallery List and Program