The Artisan Holds the Knowledge

The group exhibition Jeux de mémoires, Ahmed Bouanani aujourd’hui (Memory Games: Ahmed Bouanani Today), curated by Omar Berrada, is arranged around archives of the Moroccan intellectual figure, filmmaker, writer, and historian who was Ahmed Bouanani. In addition to screenings of his films, access to his library, manuscripts, drawings, and other materials, the visitors are exposed to an unedited …

The group exhibition Jeux de mémoires,Ahmed Bouanani aujourd’hui (Memory Games: Ahmed Bouanani Today), curated by Omar Berrada, is arranged around archives of the Moroccan intellectual figure, filmmaker, writer, and historian who was Ahmed Bouanani. In addition to screenings of his films, access to his library, manuscripts, drawings, and other materials, the visitors are exposed to an unedited conversation about his work with three artists of the younger generation in the Moroccan art scene, thus interrogating collective memory.Sara Ouhaddou strikes a precarious balance between traditional Moroccan art forms and the conventions of contemporary art, aiming to place artistic creation’s forgotten cultural continuities into perspective and lend them visibility.

Elsa Guily: Where did you get the idea for the name Madin Medin?

Sara Ouhaddou: The phrase sums up the full-circle trip in my work that engages this process of artmaking coming from the medina. It’s the intersection between contemporary art and my original training as a designer. After doing a project with the artisans, I work with them in parallel to develop a series of little inexpensive objects that are easy for them to commercialize, alongside the artistic collaboration that brought us together at first. The money from sales goes straight to the artisans. So Madin Medin is a channel, a trademark, for sustaining artisanal work. For the biennale exhibition project, I called upon a family of jewelers scattered through Morocco between Essaouira and Marrakech.

<figcaption> Sara Ouhaddou, Igdad - Oiseaux – Birds (detail), Installation view, 2016. Photo © Jens Martin

EG: Can you tell us a bit more about the sculpture installation that you put together in collaboration with the artisans for this exhibition?

SO: I wanted to take advantage of the Jeux de mémoire project by launching an idea I had in mind: a series of masks and systems of objects that would retell popular Moroccan folk tales. There are no masks in Morocco, but there are ornaments, with silver as their primary medium. So I thought it would be possible to repurpose this medium in order to invent a new system of objects.

EG:How did you connect popular storytelling to the craft of the artisan jewelers you’ve collaborated with? To what extent were those two forms of knowledge production previously interwoven, interlinked, by the history of their practice?

SO: In his manuscripts, Bouanani had rewritten major folk tales that I know, “Yamna Mansur” and “Hayna.” Integrating folk tales in jewelry, telling a story by way of and through the fabrication of jewelry, gave the artisans a key to engaging in a new experiment because the folk tale comes to inscribe a continuity and a tool for harnessing everyone’s imaginative capacity. Every piece of this work is in some way an illustration of the feelings described in those stories. Many of the Arabic folk tales that I’ve read or that my grandfather told me have birds in them. They are the bearers of enigmas, the keys to the story. And so the masks take their inspiration from the birds’ role and their shape. The carpet represents the enigma of the bride in the tale of “Hayna.”

<figcaption> Ahmed Bouanani (forground) & Sara Ouhaddou (background). Installation view of Memory Games: Ahmed Bouanani Now (detail). Palais El Bahia, 2016. Photo: Elsa Guily

EG: What is your personal reading of the archive, Bouanani’s specific project about Berber folklore? What influence did this material have on your own perception of Moroccan collective memory?

SO:As Moroccans, we are heirs to this train of thought because his work is built around the question of the collective imagination and the challenges of inscribing a collective memory. Past generations have undertaken this work, but, like Bouanani, many have been marginalized, censored by power and made inaccessible. So participating in this process allowed me to realize the importance of seeking out those figures who initiated the work of reflecting on Morocco’s collective memory in its multiplicity and diversity, far from a monolithic national identity.

EG: In your artistic practice, to what extent to you take this idea of spiritual realization, present in the folk tale, to be a form of knowledge and transmission?

SO: It’s essential to me. Working on producing ceramic tiles, there was a link to Islamic mathematics and geometry in artisanal practice which has been bulldozed in questioning that spiritual heritage. What meaning did spiritual artistic philosophy, the precision and delicacy of gestures, have in the world of Arab Andalusia, for example? What notion of transcendence inhabited these people on their quest for perfection? The folk tale borne by those tiles was the starting point, the source of inspiration for my artistic practice.

<figcaption> Sara Ouahddou, Installation view of Memory Games: Ahmed Bouanani Now (detail). Palais El Bahia, 2016. Photo: Elsa Guily

EG:It seems to me that your practice builds upon a heritage of – among other things – symbolism and the use of symbols as conduits of communication around shape and perception, around artmaking and the imagination in Islamic art.

</p>

<p align="JUSTIFY">SO: The symbol is my artistic medium. I am concerned with the universal dimension in the symbolism of Islamic art as cultural heritage because nowadays there is a large movement towards casting off forms of spirituality. At the same time, I’ve always needed to question that spirituality. This is undoubtedly linked to the fact that I have developed an interest in an art form from an era when people were extremely spiritual: Sufism, whirling Dervishes. It’s fascinating in terms of creativity and imagination. My parents gave me those kinds of spiritual knowledge through Berber culture. My mother used to spend hours weaving rugs and contemplating, asking herself questions, singing old stories, telling old spiritual folk tales, and so on. That’s how I acquired a strong spirituality. I couldn’t imagine, for example, working exclusively in territory that was conceptual, pragmatic, stripped of spirituality and intuitive imagination.

</p>

<p align="JUSTIFY">EG: To what extent do you see tradition as a vehicle of universal communication between the local and the global?

</p>

<p align="JUSTIFY">SO:In fact that’s the first thing I asked myself starting off. How can you build that bridge between universality, globalism, and the particular context? Can you inscribe that bridge in a happy medium? I still don’t have the answer but I have a name for it: the proper place, which will draw the very specific link between context and universalism. There needs to be exchange between cultures, but not only in the realm of commodities. We know that Berber culture is a blend of Asia and Africa. It would be interesting to take another look at popular folk tales originating from both continents and better understand the genealogy of our cultural heritage, draw links, build bridges.

</p>

EG: What is your role more specifically in that exchange with artisans?

SO:As I see it, the artisan is the true creator. He holds the knowledge! Essentially I am a “trigger” of his imagination. My position between contemporary art and design seeks simply to re-establish an idea of continuity or a vessel of communication between traditional art and contemporary practice. It’s a hybrid relationship, the artistic role that I have with the artisans, and I really enjoy it. I would like someday to succeed, with the artisans, in recreating those types of micro-economies around their practice. Contemporary art is disconnected from all functions that make it possible to touch upon the full range of feelings. It allows us to ask questions about the artisanal objects that are foremost bearers of culture.

<p align="JUSTIFY">.

</p>

<p align="JUSTIFY">Elsa Guily studies art history and is an independent art critic living in Berlin, specialized in the relationships between art and politics.

</p>

Community art

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo Announces List of Participants for its 36th Edition

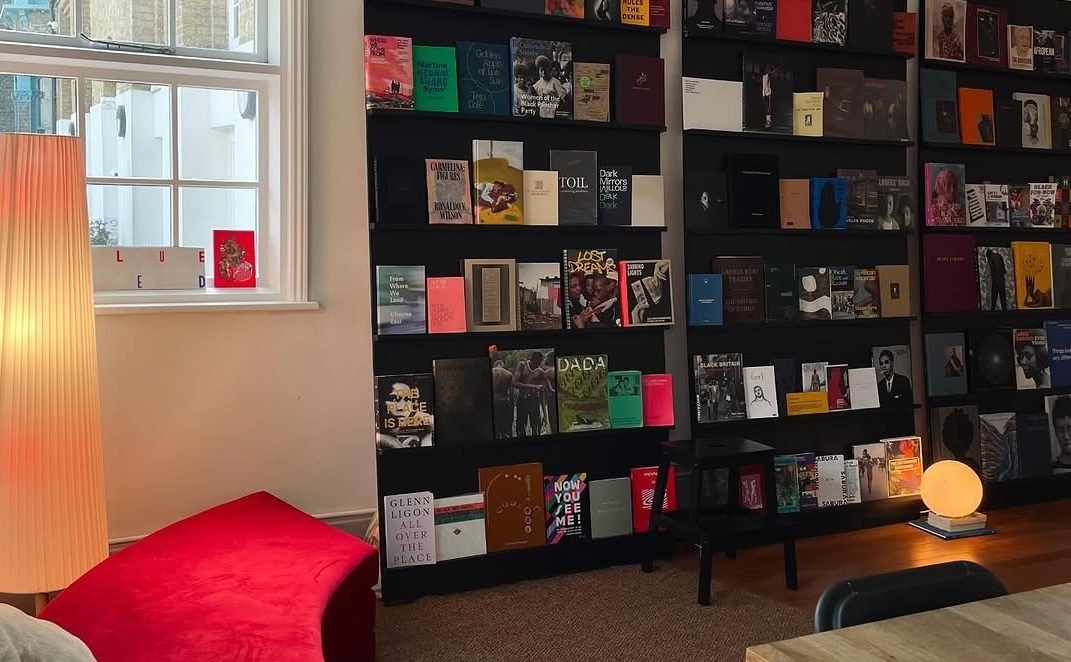

Dispatches from Tint Library’s London Pop-Up

Kampala Calling: The African and Diaspora Artists Flocking to Uganda

Cultural heritage

What Needs to be Considered When Running a Museum in (South) Africa?

The Return of the Benin Bronzes: Part of the Past or Pathway to the Future?