The Art of the Black Atlantic III

11 August 2016

Magazine C&

7 min read

C&: How would you describe the artistic landscape in Brazil? Fabiana Lopes: Brazil is a continental country, quite rich in diversity. Curiously, the contemporary artistic production which we usually access through exhibitions in institutions, commercial galleries, at biennials and art fairs, doesn’t reflect this diversity. On the contrary, what we usually see is …

C&: How would you describe the artistic landscape in Brazil?

Fabiana Lopes: Brazil is a continental country, quite rich in diversity. Curiously, the contemporary artistic production which we usually access through exhibitions in institutions, commercial galleries, at biennials and art fairs, doesn’t reflect this diversity. On the contrary, what we usually see is quite a narrow sample. Although Brazil certainly has a booming artistic scene, its production goes through a power filter. Considering that this country has the largest Black population outside of Africa, the fact that one can hardly see works by Black Brazilian artists in the mainstream is not a coincidence. What happens in the art world mirrors our society in general, where the Black subject has a defined place: of service (preferably domestic service) and invisibility. Another characteristic of Brazilian society is that race is a taboo. It is the elephant in the room. And so, openly discussing issues of race is not welcome.

That probably explains why Oscar Murillo’s project caused so much commotion in September 2014, while he was on a 10-day residency program in Rio de Janeiro. Unsettled by the environment he encountered—one of Black citizens in disenfranchised situations—the artist adopted a strategy to both survive and challenge it. He put on a white overall and joined the service staff in the residency program. He performed housekeeping activities such as cleaning, gardening and cooking, and, during the cocktail reception hosted in his honor, gave a 15-minute talk sharing his perspective on issues of class, labor and race in Brazil. There was nothing offensive in this project but by openly addressing issues of race, Murillo unknowingly crossed a line and entered the realm of the forbidden. I admire Murillo’s project because it reveals a hidden reality and offers an updated (and more accurate) view of Brazilian society. Moreover, it challenges the local artistic landscape and connects to a roster of contemporary Black Brazilian artists whose works, despite the imposed invisibility, have also been strongly political.

.

<figcaption> Peter de Brito, Autorretrato (Self Portrait) 2005, C-Print. Courtesy of the artist

.

C&: What are the challenges for Afro-Brazilian artists in the contemporary art scene? To which extent isthe lack of representation linked to Brazil’s history, especially in terms of slavery?

FL: The challenge for Black Brazilian artists is to overcome the systemic invisibility in an environment where the official discourse says that invisibility (and racism) doesn’t exist. It’s an interesting task, to say the least. In her book, Black Art in Brazil: Expressions of Identity, scholar Kimberly Cleveland calls Brazil’s complex context a paradox and says that, “Race relations and racial categories in Brazil are as multifarious and complex today as they were a century ago. Their convoluted nature largely stems from the fact that from the abolition of slavery in 1888 onward, the Brazilian nation perpetuated racial inequality at the same time that it prided itself on its image as a country unified by racial mixture, a nation that was inclusive for everyone.”

I wonder if it is possible to understand race relations in contemporary Brazil without acknowledging and understanding its history of roughly 300 years of slavery and the implications of that history in everyday life: our worldview and the way we relate to one another. It’s impossible to transform a situation without first acknowledging it. However, we Brazilians live in denial. We don’t seem to have the courage to address this subject with the honesty it requires. Facing this problem hurts and we don’t seem to be ready to go through this pain to eventually overcome it.

Despite this still largely stiff context (or maybe because of it), the production by Black Brazilian artists is rich and exciting as it addresses these complex issues and shares aspects of Brazilian society we wouldn’t otherwise see.

C&: Please tell us about some Afro-Brazilian artists and projects that you find inspiring. Where are they mainly based? Which alternative means and spaces are essential for their work and how do they empower themselves and thrive?

FL: I get quite excited when I think of the projects by Afro-Brazilian artists. For instance, two weeks ago, I saw the Parede da Memória (Memory Wall) (1994), an important work by Rosana Paulino (b. 1967). On a grid, Paulino arranges 1,500 little square bags made of and filled with fabric, hand-sewed on the edges. Printed on the surface of each little bag are the photographs of eleven members of Paulino’s family, alternated in a way that activates our memory of the family album. With this piece, Paulino creates a memorial to the Black subject, and, with an aesthetic approach, manages to close a gap within the national memory concerning this subject.

Taking this work as a point of departure, I’ve been thinking about how the issue of memory has been repeatedly addressed by artists of African descent in Brazil. On the one hand I’m thinking of Eustáquio Neves (b. 1955) and his (incredible) production as a whole. On the other hand there is Ayrson Heráclito (b. 1967) and his work Transmutação da carne (Flesh Transmutation) (2000), a project in which performers wearing pieces of jerked beef are branded with a hot iron in remembrance of what was done to the enslaved Africans in Brazil. Each of these artists—Neves from Minas Gerais, Paulino from São Paulo, and Heráclito from Bahia –- shows ways to engage with the issue of memory that probably reveals aspects that are specific to the region he or she comes from.

Thinking of Paulino’s engagement with sewing or embroidering in her artistic practice, we can draw a genealogy that would include Sonia Gomes (b. 1948), Lidia Lisboa (b. 1971) and Janaina Barros (b. 1979). Also, Paulino’s investigation of the Black female subject inspires a new generation of artists concerned with similar research, such as is the case of Charlene Bicalho (b. 1982), Priscila Rezende (b. 1985), and Juliana dos Santos (b. 1987), to name a few.

Considering the production in performance, I can name artists such as Moisés Patricio (b. 1985), who, using performative photography, seems to be trying to resolve issues related to painting, while at the same time he is using autobiographical means to articulate elements of his spiritual and social environment (Aceita?/Do you Accept? Series, 2013-2015). Peter de Brito (b. 1967) is another performance artist who interweaves considerations about the tradition of self-portraiture with investigations of gender (Auto-Retrato/Self-Portrait, 2005). Lidia Lisboa (b. 1971) uses the filter of gender and race—it is impossible to decipher her work without assessing its biographical aspects—to engage with an investigation that blurs the borders between object, performance and ritual. Furthermore there is Juliana dos Santos (b. 1987), who addresses, through her body, questions related to painting while activating issues of racial identity (Tempestade/Storm, 2013). Others are Renata Felinto (b. 1978) (Danço na terra em que piso/I dance on the ground on which I step, 2014), Michelle Mattiuzzi (b. 1980) (Merci Beaucoup, Blanco!/Thank You Very Much, White Person, 2012), Dalton Paula (b. 1982) (A promessa B/Promise B, 2012) and a few other artists who seem to be using their bodies to push for a territorial renegotiation of public spaces while highlighting the relevance of performance within the African social imaginary.

.

Fabiana Lopes is a New York and São Paulo-based Independent Curator and a Ph.D. Candidate in Performance Studies at New York University, where she is a Corrigan Doctoral Fellow. Lopes focus on the artistic production from Latin America and is currently researching the production of artists of African descent in Brazil.

.

This interview is part of our online C& series 'The Art of the Black Atlantic' taking a closer look at Afro-Brazilian presence and cultural production.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

from

Feature

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

A Collector’s Guide to São Paulo

from

Afro-brazilian art

1-54 Forum – All Podcasts Online

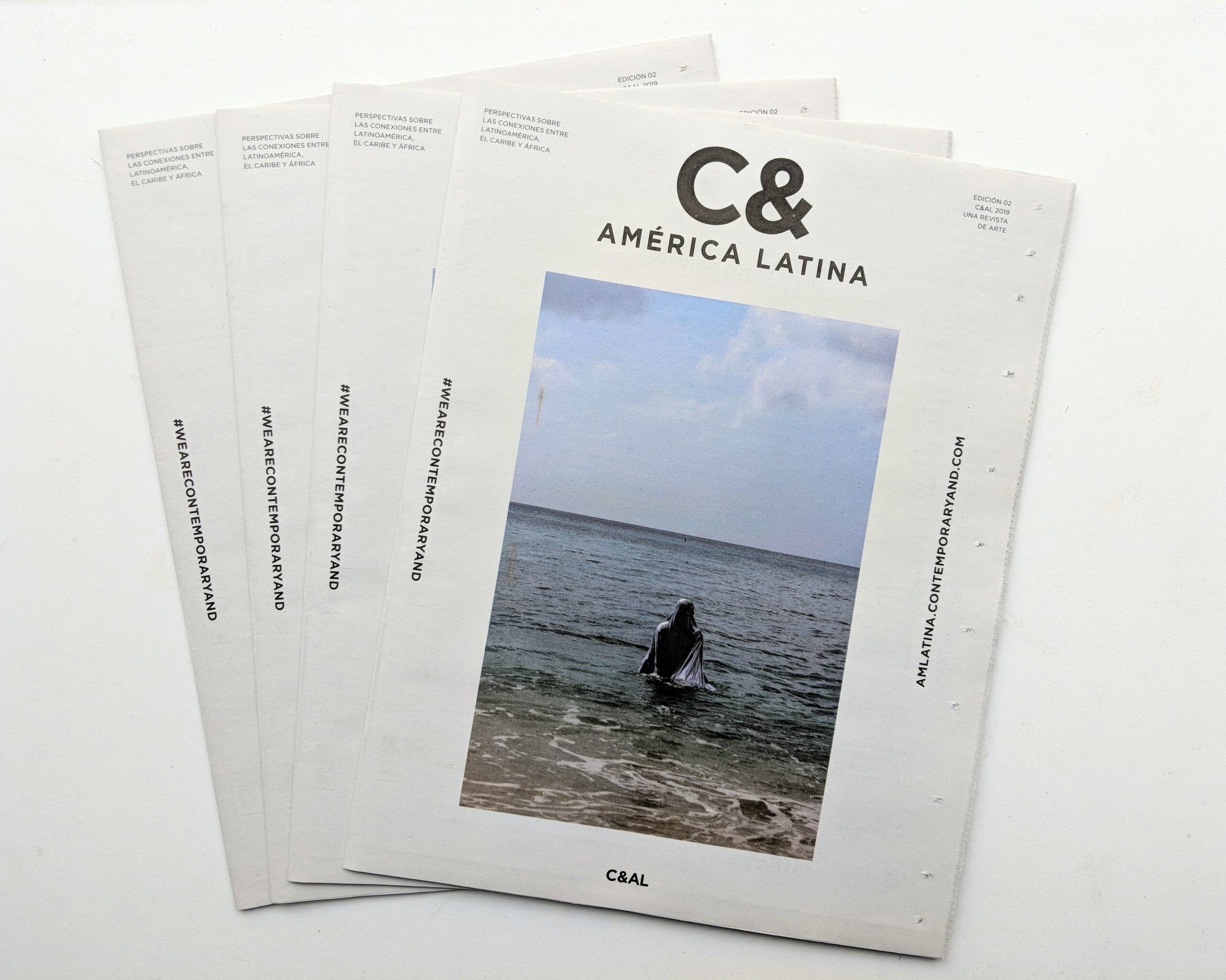

The Second Edition of the C& América Latina (C&AL) Print Issue