The Art of the Black Atlantic I

Afro-Brazilian art is often overlooked in appraisals of contemporary Brazil. The magazine O Menelick 2° Ato aims to correct this distortion while also highlighting the cultures of Black Africa’s broader Diaspora C&: Can you please tell us about the publications O Menelick 2º Ato and A Presença Negra. Renata Felinto: Our publication’s name is actually different …

Afro-Brazilian art is often overlooked in appraisals of contemporary Brazil. The magazine O Menelick 2° Ato aims to correct this distortion while also highlighting the cultures of Black Africa’s broader Diaspora

C&: Can you please tell us about the publications O Menelick 2º Ato and A Presença Negra. Renata Felinto: Our publication’s name is actually different from the famous King Menelik – it is called O Menelick 2º Ato. On our website we explain that this is an independent editorial project to think about and endorse artistic production of the African diaspora, as well as the urban and vernacular cultural output from the Black West, with special focus on Brazil. We launched the project in 2007 asa blog. In May 2010 the first printed version was published, after four years of research trying to find the right editorial and graphic blend to investigate the contemporary urban black subject in relation to its ancestral roots – an issue that still informs cultural identity today. The magazine is published on a quarterly basis and distributed free of charge at cultural events, art galleries, stores, public libraries, neighborhoods of social and political conflict in São Paulo.

<figcaption> Renata Felinto, White Face, Blonde Hair, 2013. C-Print. Courtesy of the artist.

C&: How would you describe the artistic landscape in Brazil?

RF: This question is quite generic and broad so I’ll try to be specific. In terms of visual arts I see a desperate attempt to continue the work of Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Helio Oiticica. In other words, an attempt on the part of Brazilians to inscribe themselves in a history of art that is universal, general and official. These three artists – all of them white – launched the Movimento Neoconcreto (Neoconcrete Movement), that proposed a reconciliation between art and life and challenged the concept of “the Eye” that perceived art according to Clement Greenberg’s ideas. However, this art that claims to be reconciled with life creates no space to discuss life as experienced by so-called minority groups such as Afro-Brazilians (who are a minority in terms of political power, though not numerically.) And so, to answer your question, the artistic landscape in Brazil is quite arid.

C&: What are the challenges for Afro-Brazilian artists in the contemporary art scene? To what extent is lack of representation linked with the history of Brazil itself, especially with its history of slavery?

RF: There are many different challenges. Artists have to be able to live with dignity, have access to housing, food, clothing, education, and health care. Not all of us have that. Once we get to that point, we could focus more on the creative process. Also, scholars and academics in Brazil can’t seem to understand why we [Afro-Brazilian artists] need to create visual works informed by certain issues and histories. It would be a great step forward to be able to engage freely with themes that are relevant to us while in academia, and to have our production accepted by professors. The historical context is fully related to our present situation. Our present reality is not the result of inability, but it is a result of the racist structure in place. And this structure is so efficient that black people believe they are somehow responsible for the scarcity and oppression in which they live. Slavery is very present in our current social relations.

Renata Felinto, White Face, Blonde Hair, 2013. C-Print. Courtesy of the artist C&: Can you tell us about some Afro-Brazilian artists and projects that you find inspiring? Where are they mainly based? Which alternative means and spaces are important for their work, and how do they empower themselves and achieve success?RF: Afro-Brazilian artists with some visibility are mainly located in the south-east region, especially in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and to some extent in Bahia. There are many names I would like to mention, but I will focus on the ones that have been important to my own practice as a visual artist: Rosana Paulino, Yedamaria, Michelle Mattiuzzi, Moisés Patricio, Janaina Barros, Priscila Rezende, Sidney Amaral, Tiago Gualberto, Marcelo D’Salete, Jaime Lauriano, Olyvia Bynum. All of them attended university. Rosana Paulino has a PhD in visual art, the first Afro-Brazilian artist to achieve this in Brazil. Note the gap we have: the first black artist to receive a PhD in visual arts in the USA was Jeff Donaldson in 1974; Rosana Paulino received her PhD in 2010. Many of these artists are very focused on having gallery representation, but some are taking advantage of public grants from federal, state, and city governments and have been successful (1). This has also worked well for me. C&: How do you collaborate with other Black artists or artists of African descent whose networks are in the Americas and on the African continent?RF: It is a huge challenge to know what is going on in the visual arts from the African Diaspora in different countries. O Menelick 2° Ato is our small but unique contribution to this challenge by publishing articles about, and interviews with, artists from other parts of the world. Sometimes we only introduce an image and the artist’s name. It is enough to rouse the reader curiosity. C&: What is your vision in terms of making Afro-Brazilian art and voices visible? RF: My research focuses on Afro-Brazilian artists but I don’t think we need a label such as “Afro-Brazilian art.” We should demand that the art that speaks about us and to us, as well as to others, is just called art. And this art will reflect our history, our anguish, our dreams, our myths, our images and our desires, just as the art of white artists does. If a black artist doesn’t want to address any of these themes, it is up to him or her. However, I see it as the product of a process of identity alienation, one that has been imposed on us since birth, and it is incredibly efficient. Renata Aparecida Felinto dos Santos is a São Paulo based visual artist, a scholar and an educator. She is Doctorate candidate at UNESP Art Institute and holds a Bachelor and a Master degrees in Visual Arts from the same institution. Felinto is a professor of African Art and Culture in the Art History, Theory and Criticism Graduate Course at Centro Belas Arts. Felinto is a member of the editorial board for the publication O Menelick 2ºAto. . Text translated by Fabiana Lopes This interview is part of our online C& series 'The Art of the Black Atlantic' taking a closer look at Afro-Brazilian presence and cultural production. . (1) Brazil has a specific system: Federal, State and City government offer certain grants/awards every year. These grants end up being an alternative to artists who don’t have gallery representation and don’t sell their work. Besides having a day job (many of them are educators/professors) they apply to these grants/awards. Once selected, they have funds to realize book projects, exhibition projects that they wouldn’t have otherwise. . Interview by Aïcha Diallo

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Afro-brazilian art

1-54 Forum – All Podcasts Online

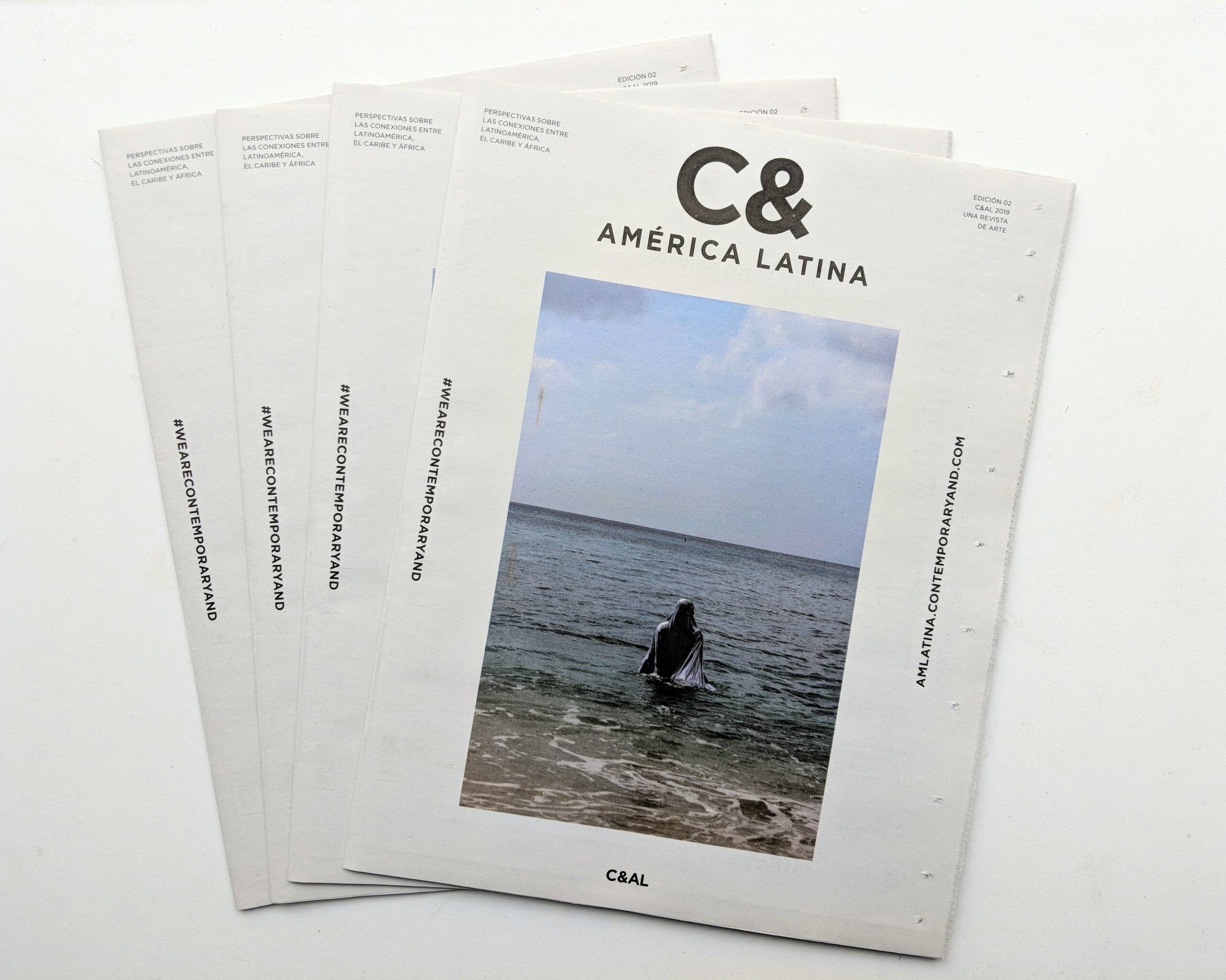

The Second Edition of the C& América Latina (C&AL) Print Issue