Tension through Patterns

With a career that expands over two decades, Odili Donald Odita’s abstract paintings burst with tension and colourful patterns. They convey messages dealing with the politics of identity such as displacement and discrimination. From being an African in America to police brutality in the US, the Nigerian-born, Philadelphia-based visual artist caught up with our author …

With a career that expands over two decades, Odili Donald Odita’s abstract paintings burst with tension and colourful patterns. They convey messages dealing with the politics of identity such as displacement and discrimination. From being an African in America to police brutality in the US, the Nigerian-born, Philadelphia-based visual artist caught up with our author Stefani Jason to talk about how these scenarios play out in his body of work,Third Degree of Separation, currently on at Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town

Stefanie Jason: Your work in the past and your current exhibition touches a lot on identity. Would you mind exploring this with me?

Odili Donald Odita: I grew up understanding myself as an African through my parents. And then I came to understand that there’s a certain sense of shame that the African has to carry in the world. A shame that deals with technology, history and its connection to the slave trade, and so on. And there’s the reality that if I’m coming from Africa, I might not necessarily be a direct product of the slave experience, which is connected to the African American experience. So there’s that division and contention. For me that’s part of the things I’m thinking of now.

SJ: Third Degree of Separation is made up of intricately designed pieces of work. How long did it take you to create the body of work?

ODO: That work probably took a year to make. If you date the work, you can see that the pieces go from early 2014 through to March 2015.

SJ: During that time there was a lot of turmoil in America, from Ferguson-related protests to the Eric Garner incident, and more. Did any of this affect your work?

ODO: Absolutely. It’s important what has happened, and that people are able to stand up to that type of police brutality. For too long there have been people who are accepting of this police violence because the justification is that there is a reason for it. But in most cases it is abuse of force or overuse of force; force that does not need to be used to that degree.

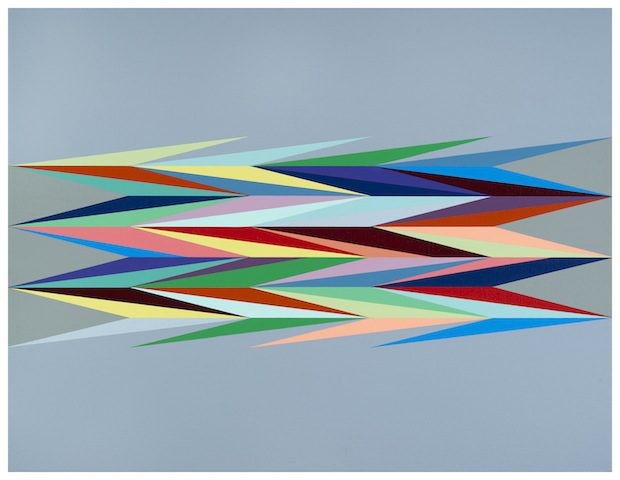

Odili Donald Odita, Surface Charge 4, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 51.2 x 66.7cm © Odili Donald Odita. Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

SJ: And how have your thoughts on these issues translated into abstract work such as your own?

ODO: It’s funny because I always find that there’s an issue with defining the translation; as if one is equal to one. It’s really bizarre to even think of that kind of translation because music is not painting and snow is not water. Even if snow originally comes from water, there’s an ingredient that transforms water into snow. So you have these situations, where bodies become victims of fists, blood becomes the result of the strike, and then you have paint on canvas. And I’m channelling these real situations and thinking in my terminology, which deals with lines and colours and forms and shapes, issues of contrast, friction and tension with these materials. And I try to create a space that conveys what I’m thinking. Usually people want a simplistic representation of these situations for their satisfaction and one has to put much greater effort into thinking them through, thinking about how these issues can transform themselves.

SJ: Bomb magazine compares your paintings to modal jazz, and in a video interview, you say that “music is a means to structure the [your] work conceptually”. How does music shape your paintings and what kind of music does?

ODO: I love music. I sometimes think of myself as a failed musician who became a painter. For me, music is something that is not only intellectual but emotional. It’s something that I respond to in that way. When I was a kid in college, I was really into punk rock. But I grew up listening to all sorts of music; my mother would sometimes listen to country music and a lot of classical music. And my father listened to a lot of highlife, early Afro-beat and juju. And I listened to the radio quite a lot. It was how I got through living in the suburbs of Columbus, Ohio, because it was really boring. I later grew into rap music, hip hop, new wave and punk rock.

SJ: And how do you relate to music?

ODO: I have this relationship to music which is something like a freeing experience. It’s helped me escape some of the doldrums of suburbia. And music, through punk rock, helped motivate my sense of political agency and being able to use myself as an agent for change.

SJ: It’s strange that you speak of punk rock. Because, like your body of work, punk rock gives off a sense of anarchy or chaos, despite its traces of harmony.

ODO: Absolutely. These relationships come through [in my painting], such as tension and space, notions of being peripheral to centrality and so forth. Going back to music, I understood that I could use it to understand cultural moments and specificities, and to understand the notion of what an artist is and how artists try to make change in society. So when it came to music, I would listen to the way the singer would sing, the phrasing of the song, the breaks, the musicality. From Miles Davis to Iggy Pop and King Sunny Adé, the music I was listening to was very specific; it was from the 1960s and 70s, and it spread across the world.

SJ: So when you were working on Third Degree of Separation, what were you listening to?

ODO: Everything [laughs].

SJ: And was there any person or one thing that sparked the creation of Third Degree of Separation?

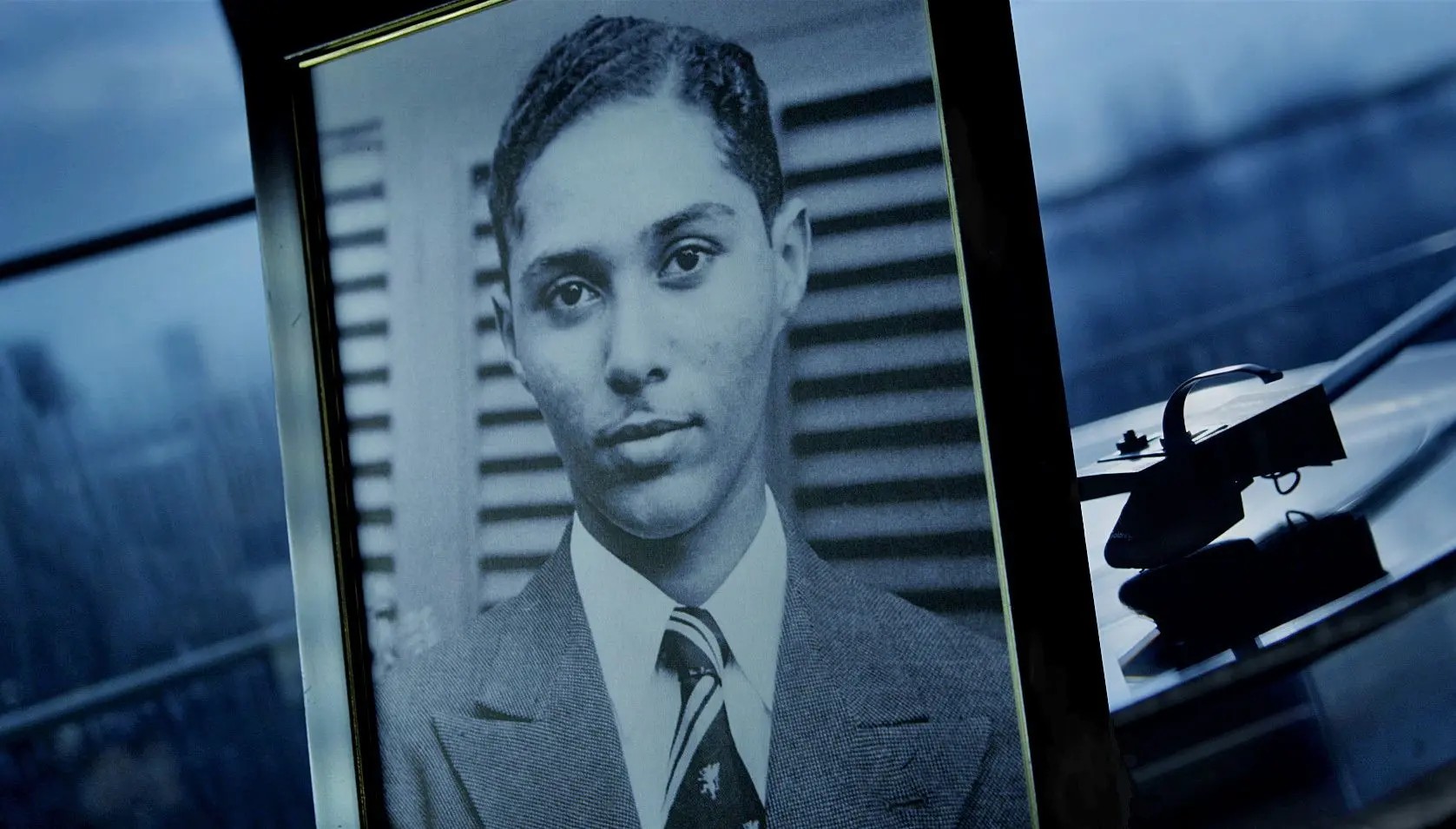

ODO: I was on a panel at the Guild Hall Center for the Visual and Performing Arts in East Hampton, New York, and I was there to give a lecture alongside other panelists. We were speaking about our work and everything just dawned on me as I was talking about my experience as an African in America. Despite having stressed my Africanness [on the panel], I also wanted to concern myself with the Americanness in my life. My father is an art historian and started the art history programme of African art at the Ohio State University. He was one of theoriginal Zaria Rebels [formerly known as the Zaria Art Society of Nigeria, so I grew up with this strong connection to African and Nigerian art. But I was also educated in the States – I had teachers outside of my father’s teaching at home. So with my painting, I wanted to acknowledge all of this. Also, my wife is Swiss, so I have this European consideration that I bring into my work.

SJ: So I guess you were faced with yourself at this time.

ODO: Yes. It was really interesting. Because I was asking myself things like, what position does my voice have within an African American landscape? Is it taken as equal or as tertiary? I was thinking a lot about my voice: is it a First World voice, a Second or a Third World voice? And what voice do I connect to? Is my Nigerian voice relevant and how is it relevant in America?

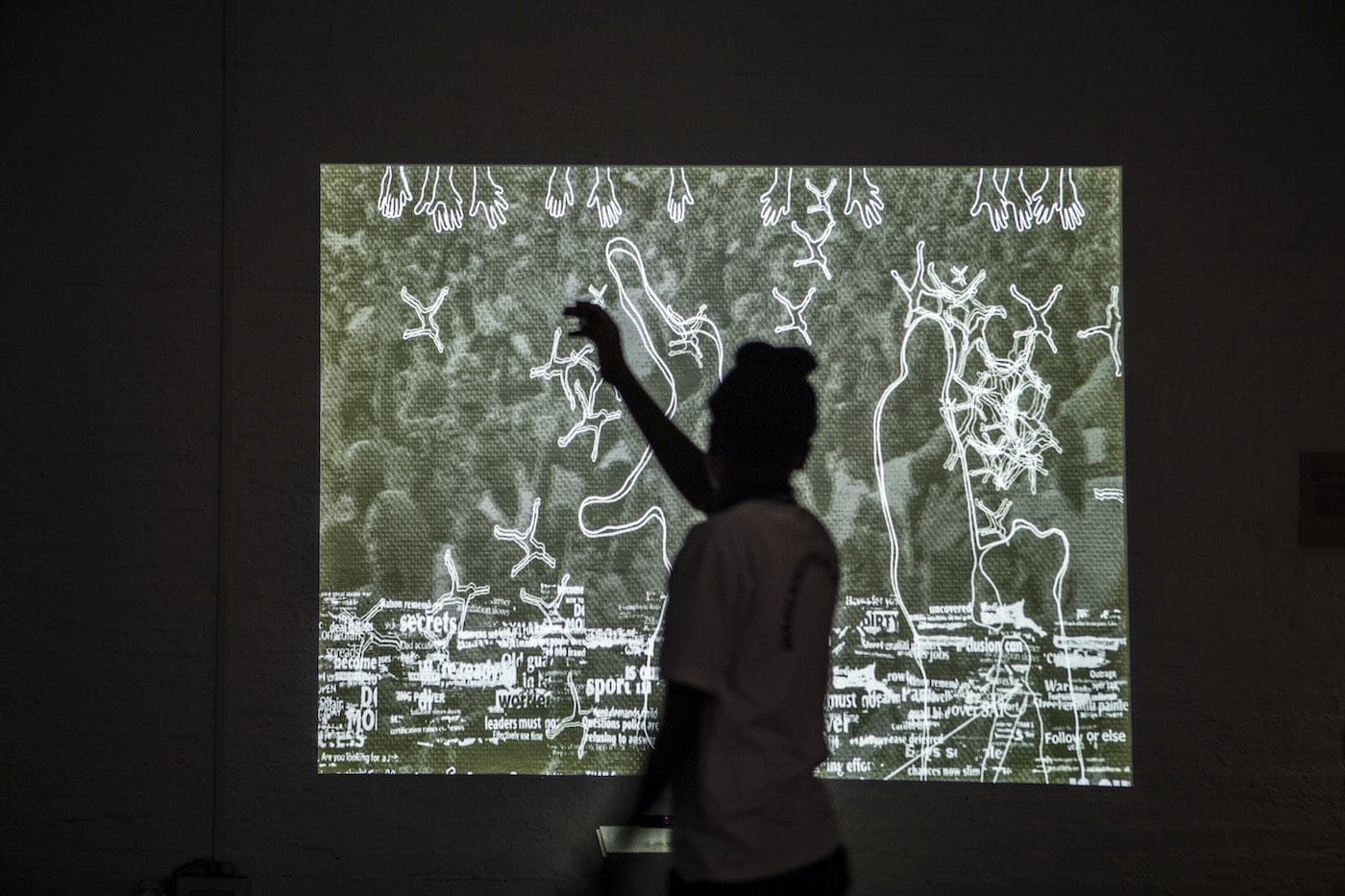

Odili Donald Odita, Accelerator, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 127 x 152.5cm © Odili Donald Odita. Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg. Photo: Mario Todeschini

SJ: Your use of patterns, space and colour in your art is bold and emits emotion. Regarding your patterns, do you have a vocabulary for them? Do you repeat the same kind of patterns? Or is each pattern unique?

ODO: The pattern for me really comes into play in the structuring of the painting. I’m taking one pattern from one situation and I combine it with another from another situation to make a third situation. I’d say that my patterns for my paintings began in 1998. I have several books with hundreds of pages of patterns. I organise them all by date and the majority of them have not been used. These patterns are the basis of food for thought for me. They could’ve meant something when I originally made them but it often happens that I come back to them years later and use them in my paintings, which might change their meaning.

SJ: You explore the theory of third spaces in this body of work and your artwork evokes a mashup of SMPTE colour bars (TV stripes) and West African prints. Would you consider incorporating digital spaces of art creation?

ODO: I can’t escape the fact that my painting is made by my hand, and my body is part of that experience as much as mind. And that’s the reality I want to maintain with my work. I know that there’s a lot of my work online, but you really have to stand in front my paintings to feel the physicality of them.

SJ: What are you currently working on?

ODO: I’m working on several wall installation projects. One for Yale University and two for the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

Odili Donald Odita, Third Degree of Separation, March 5 - April 11, 2015, STEVENSON, Cape Town.

Stefanie Jason lives in Johannesburg and is an arts and culture writer for South African publication Mail & Guardian. Her writing focus is on visual arts in the country and music.

Identity

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

In Conversation with Lubaina Himid: The Artist Set to Represent the UK at Venice Biennale 2026

, so I dream: An Ode to Stuart Hall

Contemporary art

Naomi Beckwith Unveils Core Artistic Team for documenta 16

Venice Biennale 2026 Will Follow Late Koyo Kouoh's Vision