In conversation with artist Heba Y. Amin about the artistic community in the aftermath of the Egyptian Revolution, cultural hacking of Homeland, and her work Project Speak2Tweet at this year's Dak'Art.

Heba Amin, 'As Birds Flying', 2016 Video Still, courtesy of the artist

C&: The artistic community was very much involved in the Egyptian revolution and you participated on various levels. How would you describe the situation in Cairo now, five years later?

Heba Y. Amin: Unfortunately we are in a very difficult place, collectively speaking. There is an extreme crackdown on freedom of expression. We are living in an environment of fear, paranoia, and nobody knows how they should and should not behave in public spaces, what they can and cannot say on the Internet and social media. There is a revisiting of unrest that feels somewhat similar to when the revolution was first starting. In terms of the artistic community, this widespread fear has a lot of implications because, in addition to institutions and independent art spaces being shut down, many artists, activists, and writers are being arrested for the work they are producing. As a result, people are understandably censoring themselves. There is no doubt that this is transforming the ways in which work is being produced and has put a sort of cap – for the time of being – on creative development. That is not to say that artists have stopped creating, of course not, and they will never be silenced. But it is unclear where we are headed to.

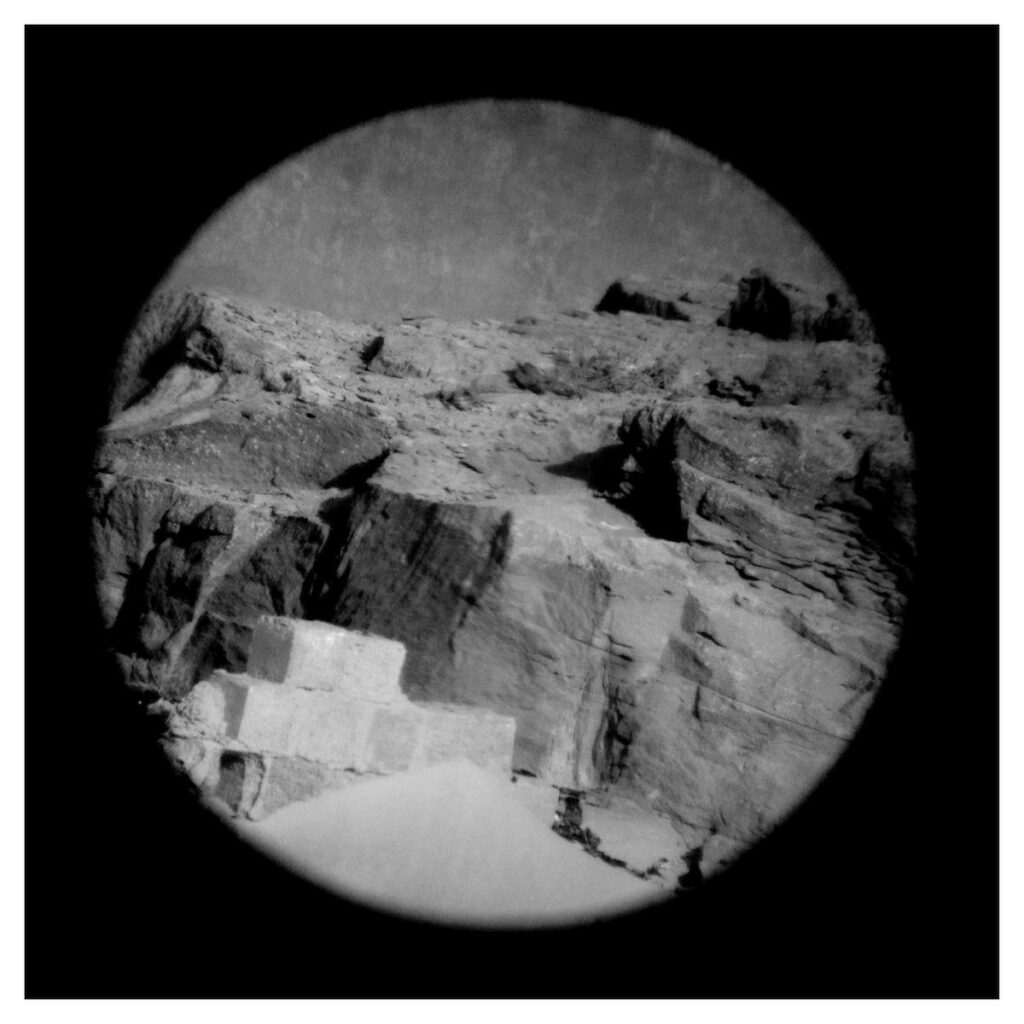

20° 52′ 35.45″ N, 17° 3′ 32.08″ W, Nouadhibou, Mauritania, from ‘The Earth is an Imperfect Ellipsoid’ , Digital Print, courtesy of the artist

C&: Do you believe there is a sort of aesthetic justice for artists to pursue?

HYA: I think there is a lot of potential for art to address political injustices but I don’t think it should be the responsibility of the artist to assume a role in political transformation. Perhaps art has the power to transform the way we see. However, there are many different strategies that artists use to combine politics with creative expression. In many cases it is effective and in many cases it is not. I think it really just depends on various factors: what is the context and what are the tools being used? In the Egyptian revolution we witnessed the use of many creative tactics like street art, viral memes on social media, a transformation of public spaces through video projects and films etc. There was a huge explosion of art that perhaps did not exist on the same scale before. Suddenly people felt the need to express themselves creatively.

C&: Talking about politics, tell us a bit about your collective, the Arabian Street Artists, which ‘hacked’ the television series Homeland.

HYA: I would like to point out the Arabian Street Artists is not a real collective, it is a parody. We use this title ironically because they referred to us on set by this name, which we found to be super orientalist and funny in its political incorrectness. We decided to poke fun at them by adopting this name. They were filming the fifth season of the series Homeland in Berlin. One of the storylines in this most recent season is about hackers and whistleblowers in the context of the migration ”crisis”. They had built a set of a Syrian refugee camp in Lebanon and were looking for graffiti artists to decorate the set with ‘authentic’ Arabic graffiti. I initially turned down the job offer because I boycotted the show. But with Caram Kapp and Don Karl, we decided to utilize this opportunity to make a statement in opposition to the show.

After a few meetings with the crew, it became clear that they had not done their research; even the references they were using were aligned with the Syrian president and would probably not appear in a refugee camp of Syrians running from the regime. We put together a list of proverbs that were critical and decided that proverbs would be a good way to go about this – perhaps they wouldn’t be so obvious. However, when we first arrived on set, we discovered no one was interested in what we were actually writing, it was merely for decoration purposes. We took this opportunity to improvise and play with the content of our graffiti to critique the show. Three months later, the episode aired with graffiti tags like “Homeland is racist,” “Homeland is a joke,” “1001 calamities,” and “Homeland is watermelon” (an idiom that suggests something is a joke). Basically the show criticized itself without knowing it. When we were certain that our graffiti had appeared, we published a statement about our subversive act on my website and within an hour of sharing it on social media, it went viral. We were contacted by media from all over the world. It resonated on such a worldwide scale in a way we never could have anticipated. It seemed many people could relate to the criticism that we raised and the fact that this is not just an innocent entertainment show that portrays fiction, but negatively shapes the way people view a very large region of the world, and this, in turn, has real consequences in the political landscape.

C&: You recently founded a real collective, the Black Athena Collective. Is this a new project?

HYA: It is a project that I co-founded with the artist Dawit L. Petros. We are interested in looking at spatial constructs and political discourses connected to the African continent. The Black Athena Collective’s name is taken from Martin Bernal’s thesis, which questions methodological assumptions embedded within Western historiography. He made the “controversial” suggestion that ancient Greece – and Europe in general – was highly influenced by the African continent. We want to explore alternative ways of addressing narratives from South to North vs. the other way around. For us, an important part of the project is traveling through these regions and looking at the landscapes and constructs of spaces people are moving through. I think we have both been confronted with the dilemma of how narratives are told about the continent, especially within the context of funding structures. There are few opportunities for artists to really be independent without catering to granting restrictions. So we are trying to extract ourselves from that dominant structure to see if we might not be able to pull out a different dialogue.

Accumulations, assemblages (III), House Frame, Yarn, Tagounite & Cape Spartel, Morocco, Archival colour pigment prints, 20 x 56 cm, 2016

C&: Finally, tell us a bit more about your digital project series Project Speak2Tweet.

HYA: Project Speak2Tweet is a project I have been working on for many years and is based on a platform that emerged in 2011 when the revolution started in Egypt. At that point, the revolutionary youth were mobilizing people through Twitter and Facebook and when the Internet was shut down they went completely off the world’s online maps. In response, a group of programmers developed a platform called “Speak2Tweet”. It allowed people to use a regular phone to call a specific phone number and leave a voice message. The sound files were automatically posted to Twitter without a third party. The idea was that people outside of Egypt could still access information and be connected to what was going on through these voice messages.

9th Forum Expanded Exhibition: What Do We Know When We Know Where Something Is? “Project Speak2Tweet: case study #1” 64th Berlinale, photo courtesy of Giampiero Assumma

I was in Germany at the time and started listening to the news on this platform obsessively. I realized really quickly that it was incredibly unique, especially as it also incorporated people that were not necessarily in the street but wanted to express their solidarity with what was happening. It became a space for people to express their emotions and speak to the world. It was through this platform that I started to realize the incredible power of using digital media in non-traditional ways.

I now have the entire archive and, as far as I know it, I am the only person speaking about it. I started a project that utilizes the individual messages and juxtaposes them with footage of an abandoned city. This project became a very interesting point of discussion and raised many issues that needed to be addressed alongside the revolution. I also feel a sense of responsibility to make this information public and easily accessible again. An archive is nothing unless somebody takes the initiative to preserve it.

I’m showing Project Speak2Tweet at this year’s Dak’Art. It is interesting for me to show it in other contexts because its multiple layers of narratives are revealed depending on where I show it and how people relate to this experience of the Egyptian revolution, which is something people have witnessed worldwide.

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

More Editorial