Sara Blokland: “Who is allowed to be in the picture?”

19 November 2018

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min read

Since 1999 Dutch artist Sara Blokland has been using photography to reflect on the complicated role of this medium in relation to (postcolonial) cultural heritages. Through her work as an artist and also curator she questions in what manner does an image (re)present colonial history, even without intention. Contemporary And: How did photography become your …

Since 1999 Dutch artist Sara Blokland has been using photography to reflect on the complicated role of this medium in relation to (postcolonial) cultural heritages. Through her work as an artist and also curator she questions in what manner does an image (re)present colonial history, even without intention.

Contemporary And: How did photography become your (artistic) articulation? What do you find the most fascinating about it?

Sara Blokland: I studied theatre and film design at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam and back then photography was a medium I used frequently in my designs and concepts. Part of my interest during my studies was the self-portrait: looking at the self and at the same time reflecting on what this does to pose and representation. I am fascinated by the medium’s closeness to the moment – looking while creating… so I took some classes at the photography department and ended up sort of being a student in both departments. Since 1999 I have been working as a visual artist and since 2010 also as a curator / researcher in the visual arts. In both I put a strong emphasis on photography as part of social histories, focusing on themes such as identity, representation, migration, colonial legacies, and detachment.

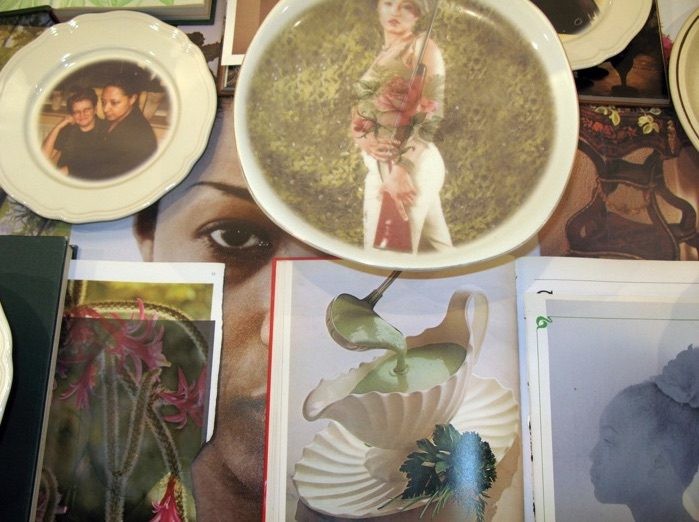

Sara Blokland, Reproduction of family part 2, 2007. Installation: ceramics and photography80 x 250 x 70 cm. Courtesy LMAK Gallery NY

C&: A recurring theme in your work is the relation between post-colonial history and visual representation. How do you examine the influence of colonialism and Dutch imperialism in your work? And how do you implement this visually?

SB: My visual work consists mainly of installations with photography and video. Photography documents and archives, but at the same time reinterprets and manipulates the world that has been observed. It is precisely this last aspect that is interesting to me as an artist and researcher because representation takes shape within it. So, by focusing on these topics I am asking, in what ways does an image (re)present colonial history, even without intention?

Through new visual and textual interpretations and reinterpretations of photography in particular, my work often focuses on the archiving of the event in the photograph, the context of the photograph, and the photograph as an object (the photograph as existence in the world). My work moved from a focus on the self-portrait to family portrait to a cultural history of the family portrait to a cultural reflection on their and my history to colonial and post-colonial history.

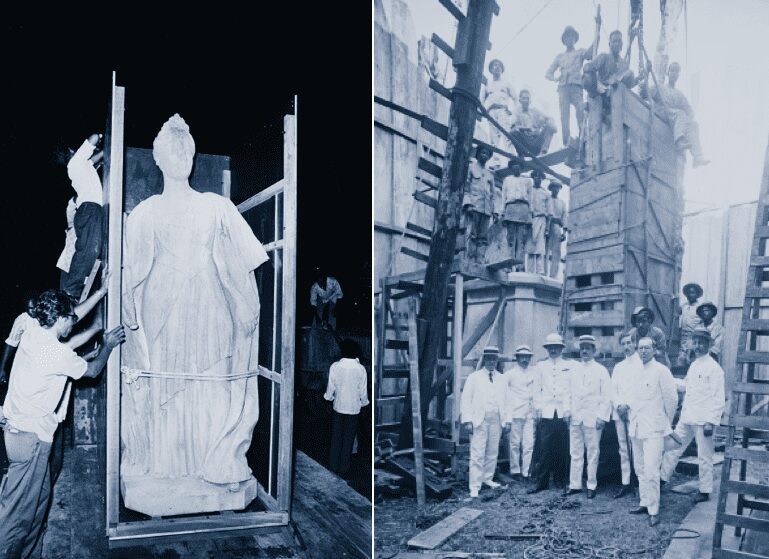

Sara Blokland, Srefidensi, 2016. Courtesy the artist. (The statue of Wilhelmina – research project. A photographic perspective on histories of resistance and emancipation in Suriname)

C&: Your project “Srefidensi” is a study of the photographic representation of resistance and emancipation of the Surinamese people. Can you tell us something about the process and intentions related to this work?

SB: Photography plays an important role in many stories, but a lot of stories about Suriname are unknown. So it was a search for stories and protest hidden in different archives. Not all photographs are stored in a way that you can see a history of emancipation through those images, you need to connect the dots. For example in the history of the photographs of the statue of Queen Wilhelmina, the Dutch queen. The statue originally stood in the center square of Paramaribo. You can find pictures of 1922, where the artist poses next to his creation in his studio. Then images with people transporting, adoring or displacing it; all in the context of a colonial history. The different connections with the statue become visible. Like when in 1923 workers sit on top of the transportation crate, while below them the white men in white uniforms are posing in front of it. This shows colonial relations of power. And you see Surinamese people taking down the statue just before independence day in 1975. The pictures are all very consciously staged and raise question like: Who is important and what is the relation to the statue? Who is allowed to be in the picture? And where are they positioned in relation to the statue? From these images you can derive and determine the power relations regarding the statue and thereby the Dutch colony. I visited different archives to find these photographs and to see the (changing) colonial relationships. So in a way it is often documented but not with the intention of showing protest, so it also about decolonizing the context of the photographic image and showing how the gaze through the camera is a colonial one.

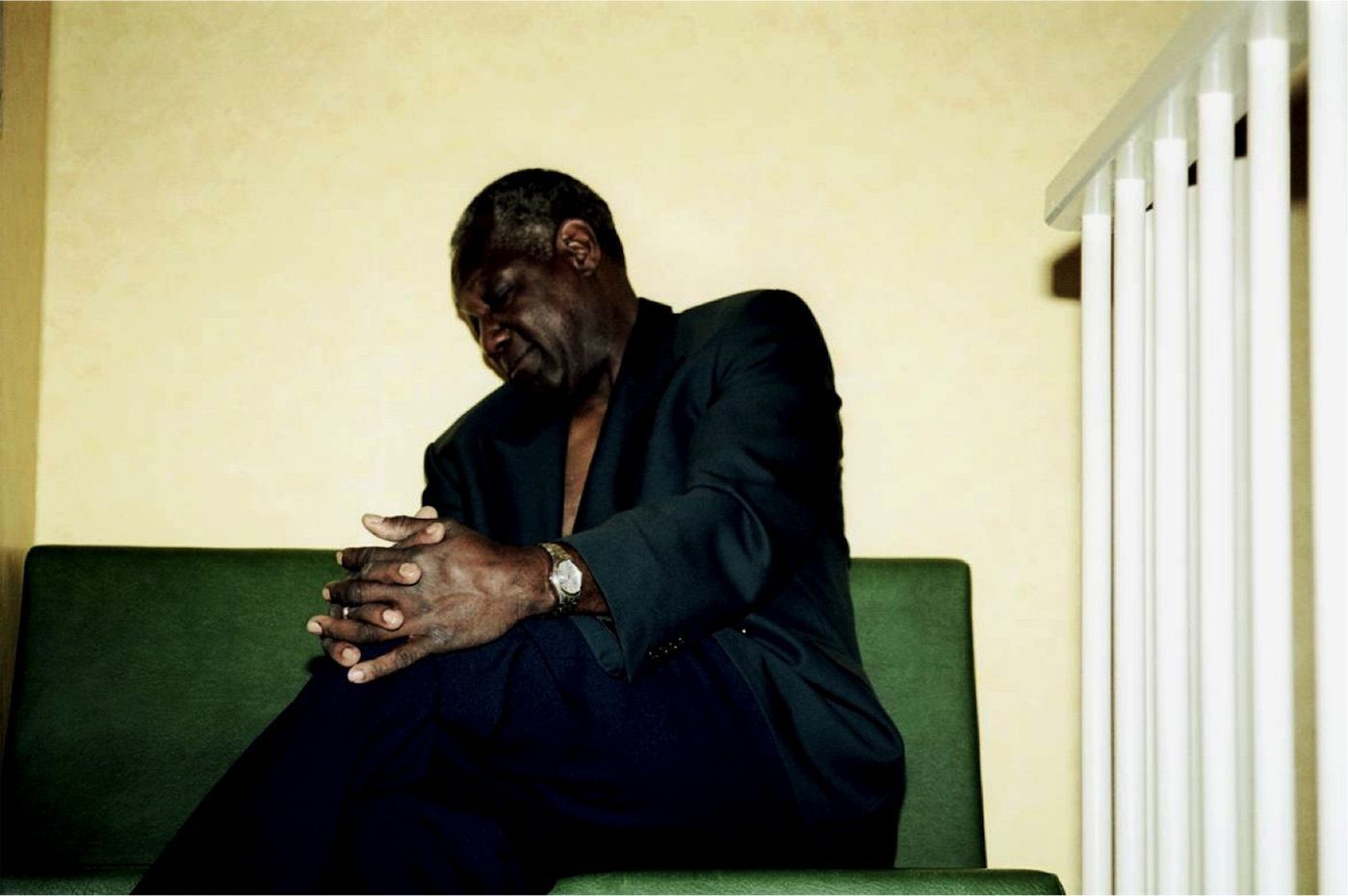

Sara Blokland, Related: A photographic performance, 2007. Photography, Inkjet print on paper. 110x160cm. Courtesy LMAK Gallery NY

C&: In which way do you think photography operates as a form of political protest?

SB: We are living in a hyper visual era where time, ideas, and actions are often instantly connected to an image – a picture or video. So photography becomes more and more a language that develops its own code. In this code a photograph is no longer an illustration of an event but a personal testimony (through social media, etc.) and therefore a statement of protest.

C&: How would you describe the art scene in the Netherlands? Especially in times of far right movements and populists like Geert Wilders or Thierry Baudet?

SB: I think there is a strong movement of art and activism going on in parts of the Dutch art world. It is no longer about connection but more about visibility of new perspectives. But if you look at the traditional art world, it is still very quiet and there is a big gap between the artists focusing on colonial history and activism and those working in the arts “as a world of its own” with no strong connection to the here and now. Personally I feel a bit in between these two worlds.

Sara Blokland (1969 NL) is a visual artist, independant researcher and curator of photography. She lives and works in Amsterdam. She studied at the Rietveld Academy (BA in photography) and graduated at the Sandberg Institute (MFA photography and video) in the Netherlands and receives a MA in Film and Photographic Studies from the Leiden University.

Interview by Theresa Sigmund.

Sara wants to thank the Research Center for Material Culture.

Read more from

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Read more from

The Entanglement of Migration, Indigenous Peoples, and Colonialism

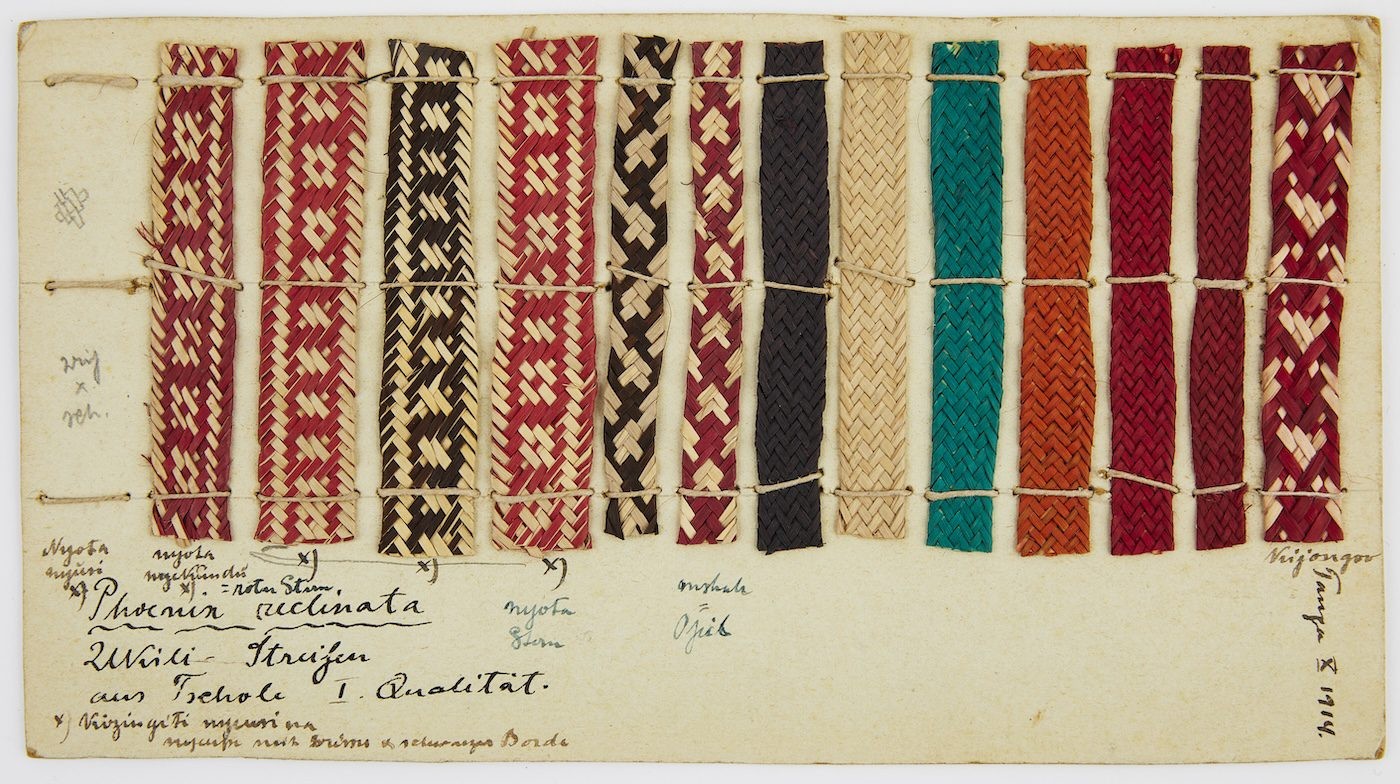

AMANI kukita | kung’oa - German and Tanzanian Perspectives on a Colonial Collection