Recipe for the Non-aligned

C&: In 2010, you co-founded the Clark House Initiative in Mumbai. Tell us a bit more about how it started and the vision behind it. Sumesh Sharma: Clark House was co-founded by Zasha Colah and me in 2010 as a curatorial collaborative. Clark House is just off a roundabout not far from the Mumbai port. …

C&: In 2010, you co-founded the Clark House Initiative in Mumbai. Tell us a bit more about how it started and the vision behind it.

Sumesh Sharma:Clark House was co-founded by Zasha Colah and me in 2010 as a curatorial collaborative. Clark House is just off a roundabout not far from the Mumbai port. On that circle you find the police headquarters, a museum established by the departing colonials, and a gallery of modern art. We were in a disused shipping office sharing space with filing cabinets and storage, and many other people who had come to make the space their home. This internationalism became part of our mission because we did not want to disturb these histories that were left behind. In addition, our space was created just after a debilitating world recession – institutions were interested in political or experimental practice, and the protagonists of the art market were sticking to what they knew. There were many barriers in India – for example, not speaking English stood between you and the art world.

From the beginning we had a very close relationship with the Sir JJ School of Art, its printmaking studio and Prof. Anant Nikam, whose students such as Sachin Bonde and Nikhil Raunak became founding members of Clark House. It has become an artist association and a collective where our personal visions come together through exhibition making. My work focused on immigration advocacy, alternative art history, conceptual practice devoid of conceptual aesthetics, and an understanding of the realpolitik through culture.

Today we hold a common vision: one that strives for an art system that is equal and equivocal when it comes to race, gender, and language. We want to inhabit a region that is really devoid of the malaise of caste and untouchability, where untold histories are finally told. We see our politics in our production, in our diffusion and our internationalism.

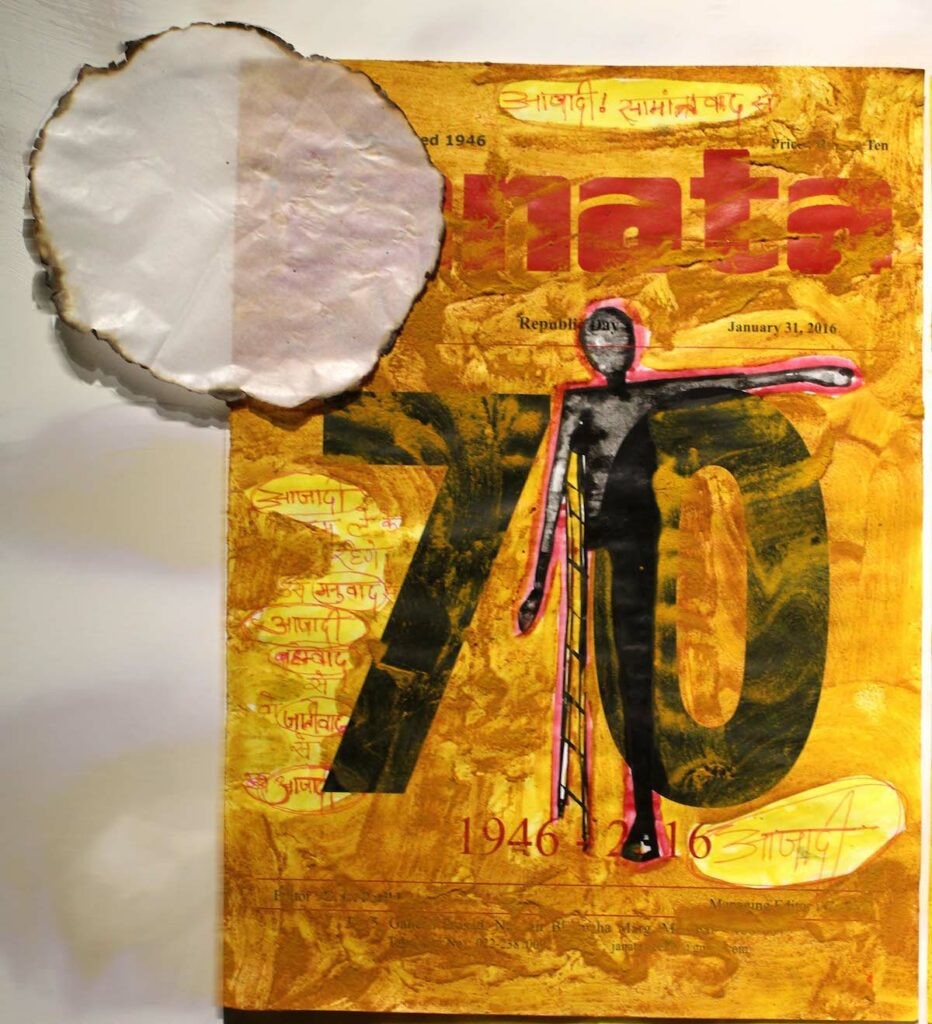

<figcaption> Naresh Kumar, Combustion, Drawing on Magazine pages ( political and social, concerns Magazine called Janta ) , tracing, paper, Turmeric, powder,water color etc . 2016

C&: Do you see any connections and perspectives between Africa and South-Asia?

SS: I do not believe in South Asia. Africa was a term the Greco-Romans used for Tunisia. We must accept the role temperature, climate, and geography play in culture. Our contemporary world allows us to live in Vancouver while we’re anchored in the Punjab through Skype, youtube, Facebook and international calling cards.

Mumbai and Cochin – where I come from – are both ports on India’s west coast, facing Africa. Africa sent us music, coconuts, food by way of the Portuguese, and it sent us our spiritual bearings. Somalia shares our cuisine. We have more commonalities with someone in Mozambique or Zanzibar than with someone living on the border of India abutting Tibet. Because we look different – and that is also questionable – we don’t see a natural affinity with Africa, but very few people know that the largest Diaspora of Indians living on any continent is Africa, specifically South Africa.

Yes, we have been working closely with people from the African continent, but not in the form of any project, as we are aware of the neo-colonial project India and China are pursuing in West Africa. Rather, we seek inspiration in the idea of Black Consciousness and a vocabulary of industrious dissent against all that has conspired to stop things from happening.

<figcaption> Yogesh Barve, 'Under the microscope, in reality' Plunger, _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _, adhesive. 2016, courtesy of the artist

C&: You are interested in the immigrant culture in francophone contexts. In which way?

SS: I practically came of age in France. I went to a university in Aix-en-Provence on a scholarship and lived on very meagre means. Before that I had never studied French, I learnt it on the street – my friend Omar Fassatoui would call me a parrot. My student hall in Aix housed students coming largely from West Africa and the Maghreb. France opened up Africa to me in ways I would never have experienced in an anglophone environment. I joined a group interested in politics and spent time with many of the young Arab Springers over many bottles of Rosé.

I also remember coming to use the free internet with my friends Victor Mako and Cheick Diaby at the Centre Georges-Pompidou in Paris. Those days were so precarious we could hardly afford the train tickets to get back home to the suburbs, so museum tickets were out of the question. There was this great wall that stood between me and my dream to be a curator. Inaccessibility in France draws many parallels to our caste system. It is characterized by deplorable or nonexistent opportunities and today these issues have become much more engaging and urgent.

I owe it to my friends that they kindled my interest and I owe to myself that I walked through the doors that were opened for me by organizations such as the Kadist Art Foundation, Beton Salon, and many others.

Immigration is not an opportunity, it is more like a fundamental right. All species migrate and immigrant culture is what makes a place vibrant. My hometown, Mumbai, is dying a certain death because of parochial anti-immigration xenophobia and politics. And I think as a curator, being an immigrant is the best thing to be.

<figcaption> Saviya Lopes, Yes,she is a virgin' , Thread and adhesive on wood 2016, courtesy of the artist

C&: You are part of the curatorial team of this year's Dak’Art. What is your focus?

SS: Simon Njami’s vision of non-alignment as a strategy for an art system that opposes the indifference of the art institutions and the art market is close to the Clark House scheme of things. My exhibition is not an Indian pavilion nor do I represent India – in fact, the biggest demographic in the exhibition may be middle-aged French men.

I present five collaborations that mimic modernism in the sense of the architecture and aesthetics of a time that was pioneering both in terms of modernism and solidarity.

India has no solidarity with Africa, we despise Africans because they share our color – and we are not proud of being Black. Every other month we experience the public lynching of an African student or woman crossing the street. I always feel extremely distressed and angry in the face of these incidents but also when I hear foolish, uninformed stereotypes about Africa. The collaborations reflect the idea of genuine friendship and the works were all carried here by people in their suitcases. Kemi Bassene, Ouso Chakola and Aurélien Froment are here putting together the works of around 30 artists, and they are not in conversation with them, so the creative procedure is happening as situations and possibilities arise.

My project is a criticism of trade in Africa, especially when it involves neo-colonial interests. However, I do not want to demonise trade, in fact, my project is based on the lives of the thousands of Sindhi traders who left Sukkur (now in Pakistan) to make lives in West Africa as traders. They were called Sindhwarkis or Sindhi Handicraft Workers, as their initial commodity of trade was textile. They became nationals of the countries they lived in, with their hearts in Mumbai, having left Pakistan after partition.

I explore the possibility of non-authorship as an option of the non-aligned. Collaboration is the recipe for non-authorship and an art practice that is sustainable politically. Ethically it stands outside the art factories of our time and the mega museum budgets, funded by art galleries.

https://vimeo.com/169994389?utm_source=email&utm_medium=vimeo-cliptranscode-201504&utm_campaign=28749

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

Curation

Naomi Beckwith Unveils Core Artistic Team for documenta 16

Paula Nascimento and Angela Harutyunyan Announced as Curators of Sharjah Biennial 17

Venice Biennale 2026 Will Follow Late Koyo Kouoh's Vision

Diaspora

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones