Patrick Eugene: Where Do We Go from Here?

Contemporary And: Your latest body of work borrows its title from the last book written by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., before he was assassinated in 1968. Why is Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? important to you? Patrick Eugene: The book provided hope for trying to find community among what …

Contemporary And: Your latest body of work borrows its title from the last book written by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., before he was assassinated in 1968. Why is Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? important to you?

Patrick Eugene: The book provided hope for trying to find community among what could have been considered a broken people. Steps for how to overcome tragedy, confide in each other, and move forward.

C&: What are the common themes between Dr. King’s book and this body of work?

PE: The book just spoke to me coming out of a pandemic, witnessing the Black Lives Matter movement. One of the biggest questions was what artists are going to create during their lockdown. We were excited to see what the work would look like. That was the question that I continuously asked myself: Am I going to make work that speaks to this time specifically? Or do I actually sit down and reflect on other moments of time where people had to get together and overcome? That is pretty much the gist of this show.

<div class="imwrap"><div class="row">

<div class="col-lg-12 col-md-12 col-sm-12 col-xs-12 imagecont">

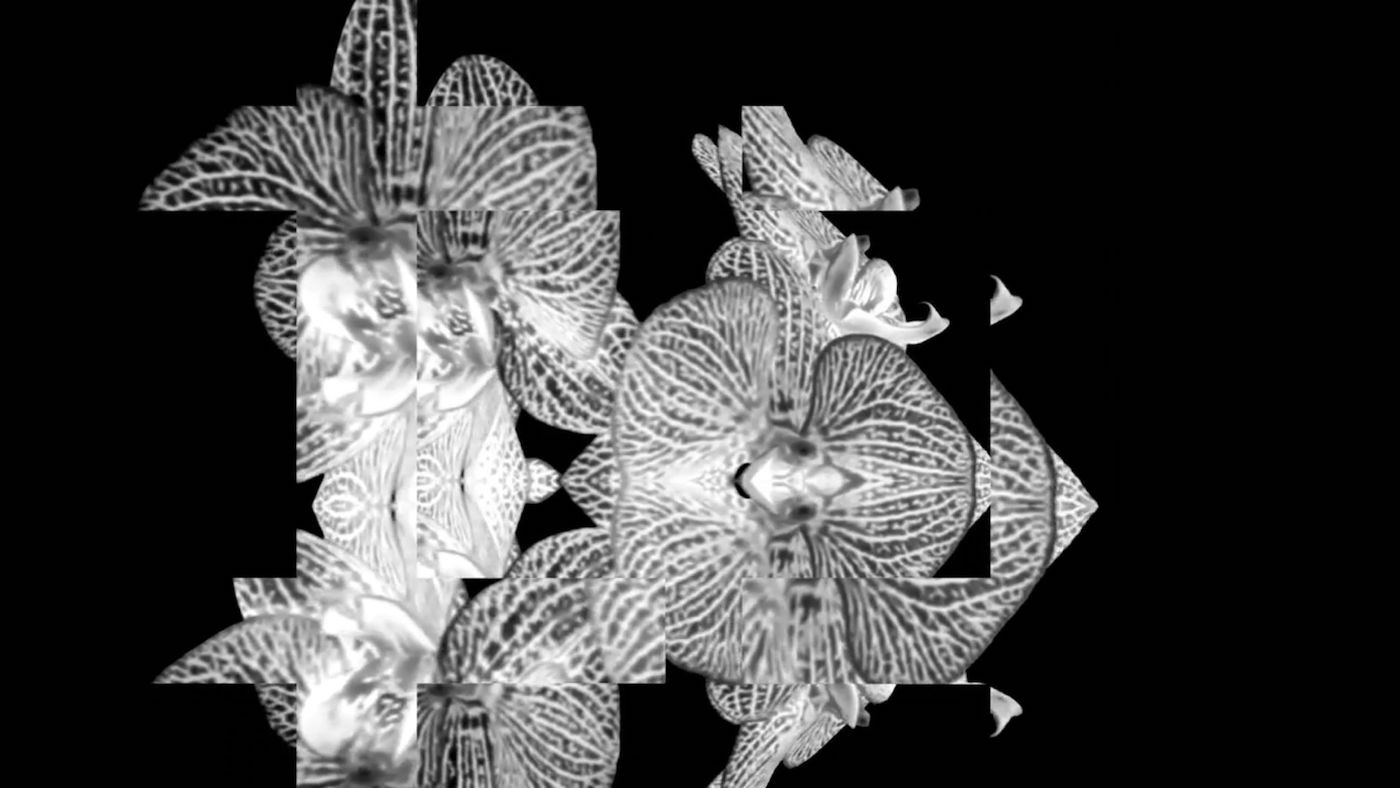

Patrick Eugene, Where do we go from here?, Installation view at Gallery 1957.

C&: Apart from literature, did you draw inspiration from other art forms or epochs?

PE: As you can see, a lot of the pieces do not immediately feel like they are from our current moment. That is because I chose to highlight a period of time that was completely inspirational to me because of the music I listened to. I listened to a lot of jazz. The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s was a golden period in New York City where Black people came together and really did beautiful work – visual arts, music, dance, theater, and other forms of artistic expression. And it created a sense of community. I wanted to continue this conversation, so I just dove into it.

C&: Why was the act of prayer important to you while making this work?

PE: Prayer is just a part of my normal life. I do not necessarily go in every day and do a ritual, but it is always on my mind. It has become a part of who I am overall. For sure I believe that there is a spiritual aspect to art and to all forms. I make sure not to forget that.

C&: The skins on some of your figures are colored in shades of red-brown. In other works you have made, figures are depicted in black and browns. What guides these color choices?

PE: I explore colors, so there are different colors that may not be your typical skin tone but I think it is fun. Some of these reddish tones that I used in this new series, I used them once I discovered that laying those colors on top of other colors creates a depth and a glow in certain skin pigments or skin colors.

C&: So your primary interest is in color, and not any assumed ideas of what “Black figuration” ought to look like?

PE: I look into my immediate family and see a huge range in skin tones and colors among my brothers and sisters, myself and my son. But in this work there may also be a drastic color that is not as natural – that is part of my abstract side. That is me being interested in color. It made my figures glow. I thought it made a lot of sense for what I am doing technically and also the final product, because that glow is obviously within us all as Black people. I do not think anyone glows more than us, and so I thought that it was just beautiful.

C&: Why are your paintings shorn of period detail?

PE: Removing some detail and allowing the mind to explore and the viewer to kind of vibe to that piece for a little bit – that is the most beautiful part of this for me. I think it stems from my abstract background, where it is kind of hard to explain an abstract piece as much as we like to try. It is hard because a lot of it is intuitive, in my opinion a lot of it is guided from somewhere else. To sit down and break down each detail of an abstract piece is almost impossible. So I try my best to use that in these figurative works. And I try not to give you too much of an expression that can lead you one way or another.

<div class="imwrap"><div class="row">

<div class="col-lg-12 col-md-12 col-sm-12 col-xs-12 imagecont">

Patrick Eugene, Where do we go from here?, Installation view at Gallery 1957.

C&: The facial expressions on your figures show no diversity of emotion – happiness or sadness, resignation or ecstasy. Would it be fair to describe them as passive or indifferent?

PE: I think there is a neutral phase – moments in time where we are thinking and we do not have a smile on our face or a frown. A neutral expression. That does not mean there is not a lot going on around or within this particular person. Allowing that openness and giving the viewer the license to figure that out on their own is probably the greatest part of this whole thing for me.

C&: If the absence of period detail frees the paintings from over-interpretation, what does the absence of diverse emotional states add?

PE: The best part is sitting back and listening to how everyone feels and views each piece. As an artist there is nothing better for me to sit at a show and say “Hey, I feel like this person is here and doing this and doing that.” It is beautiful. It opens a conversation.

C&: What were your expectations around your first show in Ghana, in August 2021?

PE: I did not know what to expect. I had never been to Africa until that show. It brought me to Africa for the first time, which was nerve-wracking, exciting, inspirational – all of the above. I did not know what to expect, crossing the oceans and bringing my work from Atlanta to Accra.

<div class="imwrap"><div class="row">

<div class="col-lg-12 col-md-12 col-sm-12 col-xs-12 imagecont">

Patrick Eugene, Where do we go from here?, Installation view at Gallery 1957.

C&: Visibility and the politics of representation are less charged in Ghana than in the US, or so one would assume. Do your Black figures have different values in a Black-dominated Ghana?

PE: Different experiences, different cultures – but then also so many similarities. I really just hope that the language in these works will cross any border and speak to us Black people regardless of where we are in the world. I hoped there would be some interesting conversations and what I received was extraordinary. The local community in Accra all showed up, which was incredible.

Globally there is an understanding that Black people have been through some things. And so although some of the politics and some of the representation is different across borders and the ocean, I think there is still a commonality in how we view some of the struggles we have gone through as a people, and some of the achievements and highlights, some of the beautiful things that we can all say about ourselves.

C&: At twenty-seven, you came to art later than many other artists. What have been the advantages and disadvantages, if any, of starting to make art in your late twenties rather than from childhood?

PE: I think one advantage about being self-taught at a later age is literally understanding who you are as a person, understanding what is important to you without influence from others. But then the disadvantages include not having explored as many different mediums as possible when you were younger, and not having gone through the institutions.

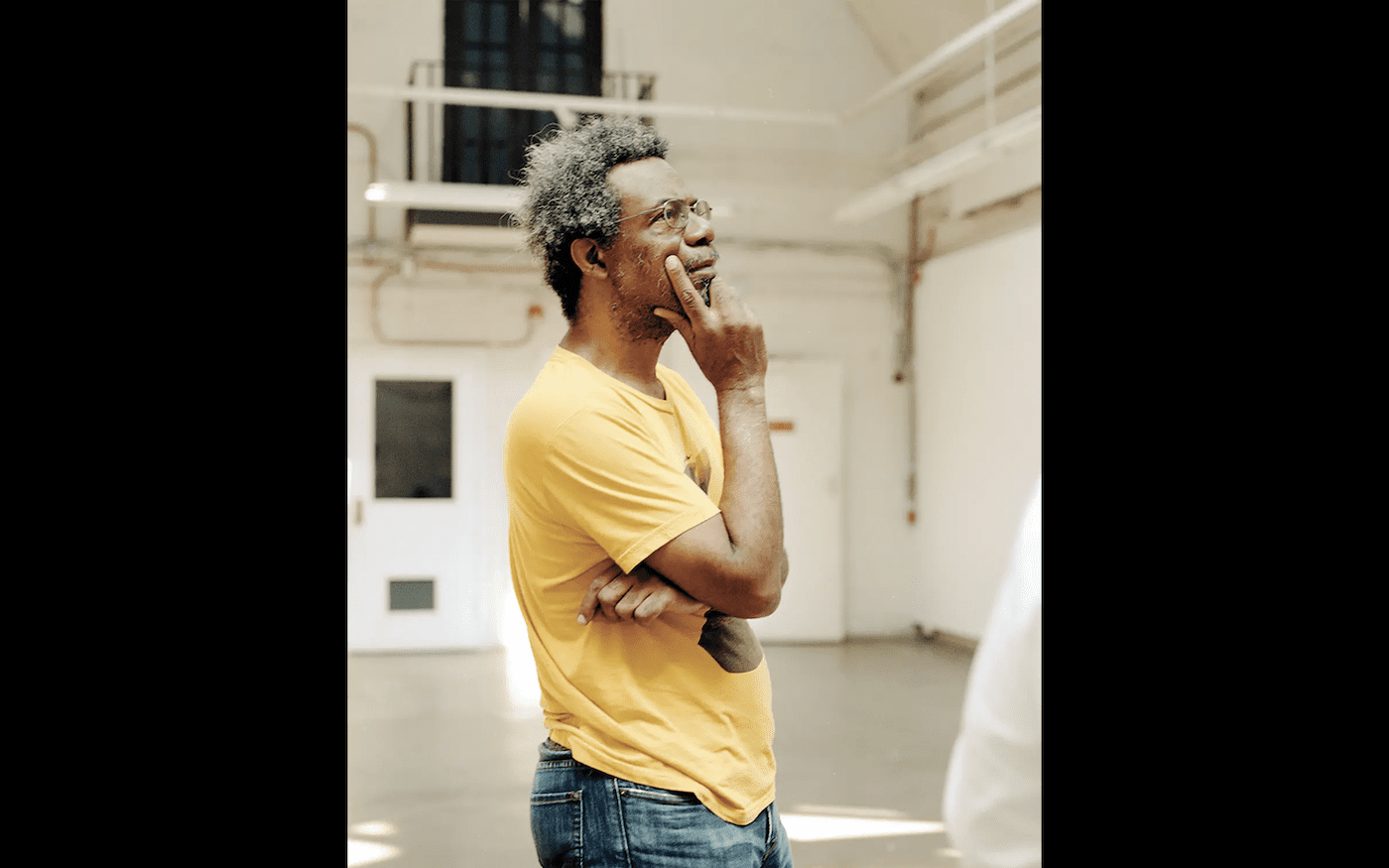

Artist Patrick Eugene‘s work reflects the raucus energy of the urban experience with the delicate patina of an old soul well traveled. Introspective subject matter, complex compositions and a multitude of experiences are filtered through a finely tuned brush to produce original artworks that transform the spaces they occupy.

Sabo Kpade is a culture writer from London.

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Race

Faith Ringgold: “I am very inspired to tell my story, and that’s my story.”

William Pope.L (1955-2023)