Occupying the Silence Between Languages

31 May 2019

Magazine C&

5 min read

As fancy yachts sailed to Venice, ferrying aesthetes to one of today’s most prestigious art exhibitions, a group of multilingual activists, scholars, and artists descended on Stuttgart, an industrial hub in the southwest of Germany. In ones and twos, they arrived by road, rail, and air. And for four days, from 23 to 26 May, …

As fancy yachts sailed to Venice, ferrying aesthetes to one of today’s most prestigious art exhibitions, a group of multilingual activists, scholars, and artists descended on Stuttgart, an industrial hub in the southwest of Germany. In ones and twos, they arrived by road, rail, and air. And for four days, from 23 to 26 May, that relatively isolated city tucked in amid sprawling hills was the space for an encounter between creative people mainly from East and West Africa. This could only indicate one thing: a manifestation ofMembrane, an international festival on African literatures and ideas.

A guest reading the festival poster. Photo: Enos Nyamor

Stuttgart may be a wealthy city, but its cultural landscape is relatively homogenous. It was perhaps in reflection of this social quality, and of the simmering political tensions in the Global North, that the festival’s three curators opted to explore permeability as an element of reconnection and recalibration. The curatorial statement specified that the festival essentially sought to exploit the potential of culture and literature as visionary spaces for contemplating and translating processes of social change in Africa.

Membrane was curated by Kenyan author Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Nadja Ofuatey-Alazard, and Felwine Sarr, and included forty-three participants drawn from Anglophone East Africa, Francophone West Africa, and regions formerly under German imperial rule. Felwine is one half of the duo that French President Emmanuel Macron tasked with reporting on the viability and validity of therestitution of African cultural heritage, and whose groundbreaking report was published in November 2018.

A panel discussion moderated by Mshai Mwangola. Photo: Enos Nyamor

While book launches and panel discussions dominated the festival, sideshows included performances, exhibitions, and a sound installation by Berlin-based Sierra Leonean artist Lamin Fofana. Lamin’s two-and-a-half-hour sound work probably left many dazzled. Titled You have Confused the True and the Real, the piece was a delicate and shamanic progression of lilting voices and electronic samples, and its effect was therapeutic. At one point, it captured the common fact of cultural and political encounters with a voice rumbling: “You discovered us, now you have to deal with us.”

Among the most distinguishable themes that pervade existence today, particularly for those of African descent in the Diaspora, and which the curators indirectly examined, is migration. It is through migration that injustices from the colonial past come to haunt former colonizers. Rapid economic migration is a direct result of the exploitation of resources in most former colonies, which created catastrophes and fueled fantasies of movement. Congolese writer Sinzo Aanza reflected on the disillusionment faced by most economic migrants, some of whom are increasingly ashamed of their fates in the Diaspora, and where they are shunted to the bottom of social hierarchies.

Visitors at the exhibition “Refracted Gazes” that was part of the festival. Photo: Enos Nyamor

The festival could have easily been an exploration by ethnographers in an industrial jungle. But it was also an occasion for thinkers and artists from the African continent and its Diaspora to examine complicated and divisive concepts, especially on the legitimacy of the notion of “African-ness.” Identity is still an unfinished game for those with hyphenated identities, and involves an invitation to either erase one’s history and embrace the present, or interweave older narratives into everyday life. In a panel discussion on African imaginaries, Taiye Selasi said: “My African-ness only I decide.” Selasi’s essay on Afropolitanism, “Bye-Bye, Barbar,” and her TED talk, “Don’t ask where I’m from, ask where I’m a local,” were suggestive of elitism, and of rejecting the entangled forces of violence and humiliation faced by the African Diaspora.

It is true that the encounter between Francophone and Anglophone Africa is long overdue, though the format of the festival excluded Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) Africa. The curators made a conscious decision to focus the lenses on former French and British colonies, and, to an extent, to those who were briefly under German colonial rule. Here, the festival subverted the silence that occupies the space between languages, opening pores for resistance and negotiation of meanings. After all, most of the authors speak in one language and write in another. These languages, of course, are those of the colonizers, but can also be instruments for creating visionary spaces, for uniting populations of African descent on the continent with others in the rest of the world.

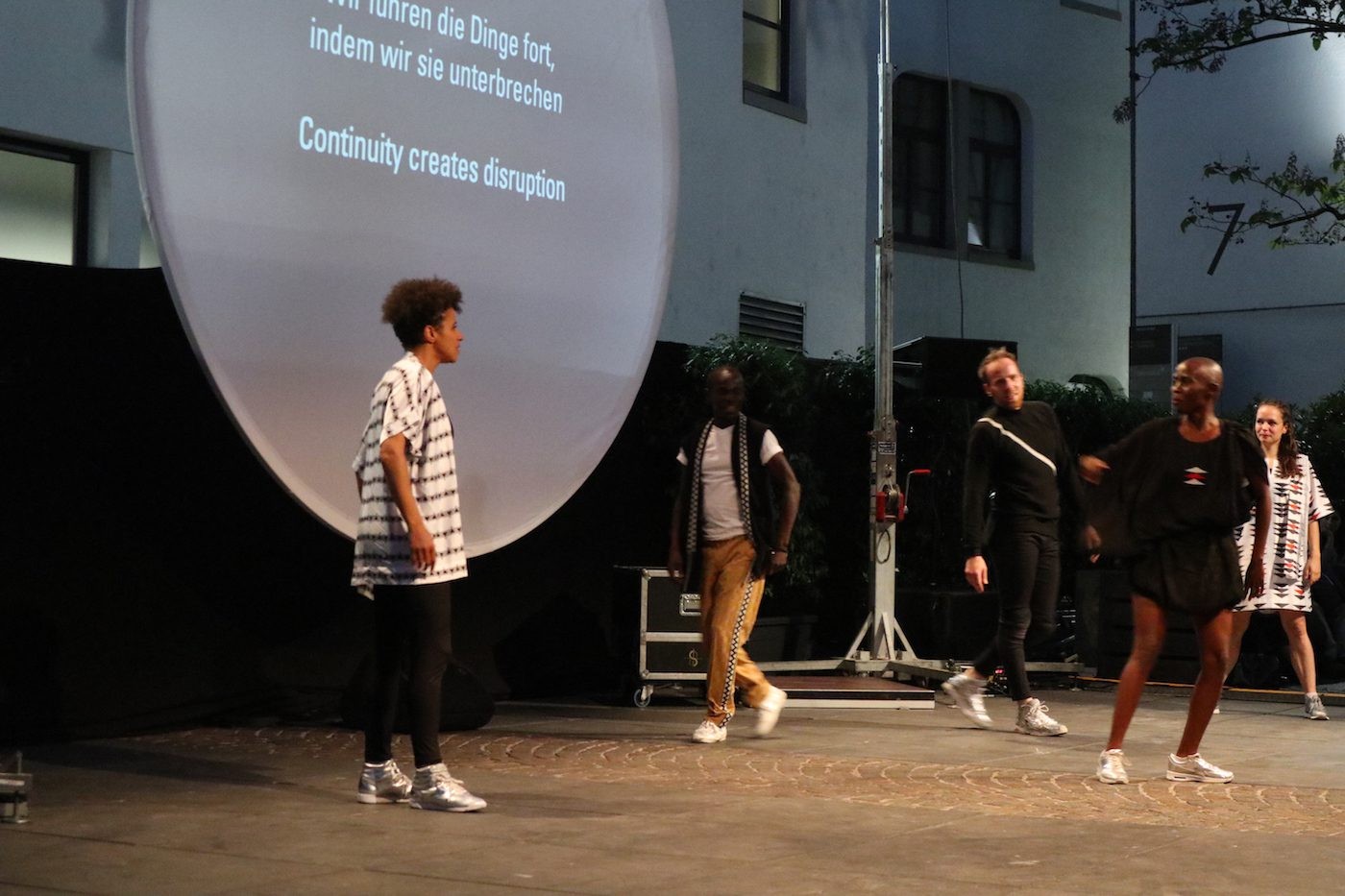

Dance performance of ‘Planet Kigali.’ Photo: Enos Nyamor

In the end, Membrane was a lantern slide that shed light on the web of tensions that loom over those from formerly colonized regions and the colonizers, and that also refracted gazes. It was evident that, even without awareness, those from former colonial empires, where racism has become a cultural element, can be themselves curtailed in perceptions and expressions. As Frantz Fanon noted in his essay Racism and Culture, racism can be a cultural element when it manifests as mental behavior and physical reactions in interactions between humans and between humans and nature. And it is likely that multiplications of encounters such as Membrane, not only among artists and scholars with African connections but also with audiences in the West, can halt the cycle through which racism renews itself. Otherwise, such festivals will be remembered as gatherings of multilinguals, of all shades of Black and brown, and just that.

Enos Nyamor is a cultural journalist based in Nairobi and a student from the C& Critical Writing Workshop which was held in Nairobi in December 2016 and made possible by the support of the Ford Foundation.

from

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

from

Literature

1949, Abidjan

Sa Sa Art Projects Reading Room, Phnom Penh