No More Waiting for the Barbarians

On the morning of the opening of Still (the) Barbarians, the third EVA International Biennale in Limerick, curated by Koyo Kouoh, we hear that Journal Rappé, a rapping duo from Senegal due to perform at the opening, was refused passage by Royal Air Maroc because officials assumed the artists’ visas were fake. Since it has …

On the morning of the opening ofStill (the) Barbarians, the third EVA International Biennale in Limerick, curated by Koyo Kouoh, we hear that Journal Rappé, a rapping duo from Senegal due to perform at the opening, was refused passage by Royal Air Maroc because officials assumed the artists’ visas were fake. Since it has taken the curatorial team and staff of EVA enormous effort to obtain visiting visas for all the artists in the first place, it is especially frustrating that protracted bureaucratic processes can so easily be thwarted by a nameless employee. But it is by no means surprising: in a world beset by migration control and an anxious guarding of entrances and exits, the censoring of movement has become a powerful tool in the hands of the privileged.

This incident holds up a mirror to all our prejudices, and involuntarily articulates a very appropriate response to the conceptual framework of the show, like an elaborate performance piece. Kouoh has chosen her title from Constantine Cavafy’s 1898 poem “Waiting for the Barbarians,” but it is South African author JM Coetzee’s eponymous Booker prize novel that I inevitably think about when I consider this incident. Coetzee‘s novel makes it clear that we need not wait for barbarians, they are already in our midst: they are here, they are here now, and they are us.

The “now” of this biennale is a postcolonial world that is still affected by the consequences of colonialism every day on political, geographical, psychological, intellectual, and physical levels. It is a reality that has persistently informed Kouoh’s theoretical approach in all her work, echoing through her projects at her arts foundation in Dakar, RAW Materials, dedicated to exhibitions, residencies and education.

Still (the) Barbarians invokes a world of personal complicity, of unequal opportunities, of hybrid forms, of asymmetrical power relations, of financial disproportion. It is a postcolonial world that Africans are very familiar with, but Kouoh extends this to Ireland, which she reads as the first place where England practiced its land grab long before it extended its Empire all over the globe. This is a bold statement, especially when she adds that Ireland’s postcoloniality is not a topic of much discussion in contemporary Ireland (and one hotly disputed by my Irish friends in the audience, whose first introduction to geopolitical politics apparently boiled down to “fuck the English”.) Given this postcolonial emphasis, it is fitting that this particular biennale coincides with the centenary of the Easter Rising, the rebellion that lead Ireland to independence from British rule. And it is in the context of re-thinking Ireland’s colonial burden that Kouoh has insisted the catalogue of the exhibition be written in English and Irish Gaelic, a simple symbolical gesture bearing a lot of weight.

<figcaption> Public Studio, Road Movie (2015), 6-channel video installation, sound installation with 6 megaphones and LED lights; 3 walls, each 7 x 12 feet, 52 min (26 min each side)Photo Miriam O'Connor, Courtesy Public Studio, National Film Board of Canada and EVA International - Ireland’s Biennial, Still (the) Barbarians, Limerick City, Ireland, 16 April – 17 July 2016, www.eva.ie

The 57 artists that are on show here – either by invitation or by open call – respond to contemporary conditions of postcoloniality from many geopolitical locations in a wide variety of ways. For example, our physical world is invariably affected by our histories, as buildings are constructed to include or exclude, and landscapes are scarred by many forms of exploitation. The Canadian duo Public Space shows a stunning six-screen video projection, Road Movie, recording a system of segregated roads that were built by the Israeli military control in the West Bank. Shot in stop-motion and set to an ambient, pensive sound track, the films travel these ‘apartheid’ roads and capture snapshots of people’s disrupted lives. Extracts from narratives are projected on both sides of three huge, staggered screens, making it impossible for the viewer to see it all from one position, literally segregating the films into various episodes.

In a similar concern with space, the New York-based artist Michael Joo has taken a dilapidated historic house on the outskirts of Limerick – the Sailor’s Home – and, with characteristic complexity and subtlety, re-animates the space with video installation and a re-purposing of architectural architraves and features. Projecting the image of an emaciated Buddha from third-century Pakistan, filmed in The British Museum, onto this very Irish but forgotten setting of seamen’s lives, he juxtaposes chains of trade, history, exchange, and migration. With no descriptions of the art pieces or labels (except for a Biennale newspaper with titles and maps), the viewer has to work hard to situate work such as Joo’s within Kouoh’s curatorial vision around barbarians, citizens, and postcoloniality, but through its use of disparate elements and ghostly remains, the artist’s work speaks loudly of conflicting histories and identities. One only has to listen, feel. And think hard.

<figcaption> Theo Eshetu, Trip to Mount Zuqulla (2015), Video installation, 7 min, loop, Installation view at EVA International – Ireland’s Biennial 2016, Photo Miriam O'Connor, Courtesy the artist, Tiwani Contemporary and EVA International - Ireland’s Biennial, Still (the) Barbarians, Limerick City, Ireland, 16 April – 17 July 2016, www.eva.ie

Perhaps visitors to the Limerick Biennale would find works that concern Africa or originate from African or diasporic artists easier to situate within the show’s conceptual framework, because so many of these artists live hyphenated lives, moulded by their personal histories. For instance, Theo Eshetu’s three-screen projection documents a creative ritual born from the fusion of divergent religions. It records a pilgrimage to a sacred site, Mount Zuqualla in Ethiopia. Highlighting the cross-cultural aspects of various belief systems and set against a soundtrack of hip hop and Bach, it visualises a richly syncretic present.

Godfried Donkor’s Rebel Madonna Lace Collection tells a story of cross-pollination and traffic through the medium of lace, an ongoing concern in Donkor’s work, relating to the labour of enslaved people who supplied the cotton yarn for what became exquisite status symbols in the West. Working with artisans in Limerick where lace-making is an ancient and now threatened craft, an intricate piece was made based on Donkor’s large mural drawings of contemporary Kumasi in Ghana. Juxtaposed with this are two mannequins wearing machine-made West-African lace, which is popular in Ghana. Sporting a straightjacket and an orange prison jumpsuit, these three-dimensional examples speak about the circumstances of lace production in Limerick, playing with associations of isolation, incarceration, patience, freedom, and also wealth and beauty. In this installation, the past and the present connect the local to the global, capturing a complex network of trade and traffic in an artwork that also portrays a very personal story.

<figcaption> Godfried Donkor, Rebel Madonna Lace Collection (2016), Installation shot from EVA International – Ireland’s Biennial, 2016, Photo Miriam O’Connor, Courtesy the artist and EVA International - Ireland’s Biennial, Still (the) Barbarians, Limerick City, Ireland, 16 April – 17 July 2016, www.eva.ie

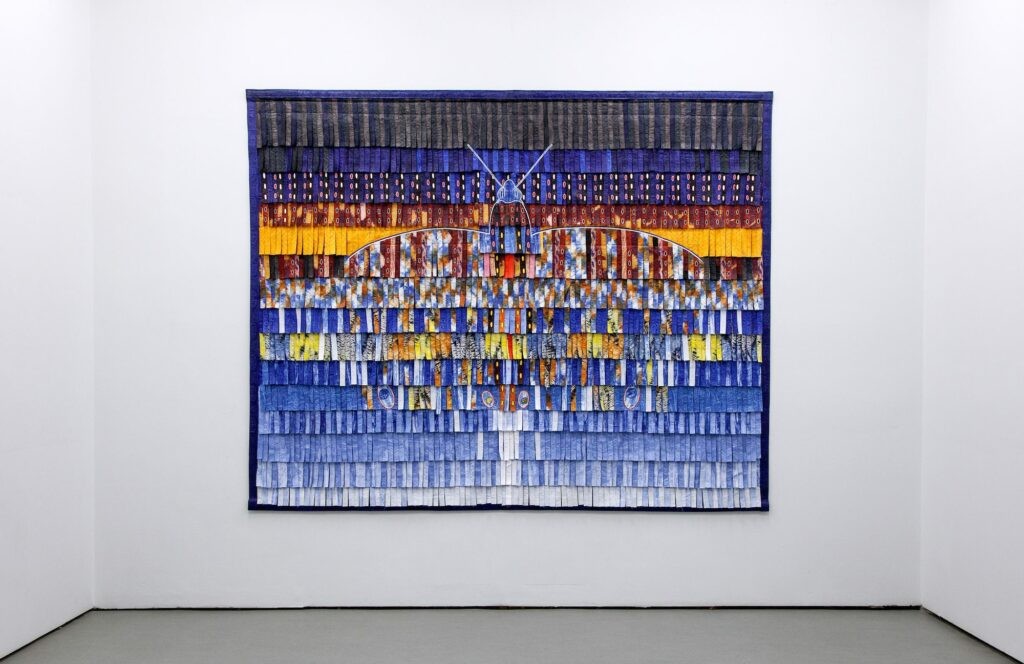

Besides the effects of postcoloniality on the physical environment, on architecture, and on personal histories of migration and acculturation, projects involving translation have an especially strong resonance with the postcolonial condition. Apart from the translation of the catalogue, this is also indirectly present in the work of Bamako-based Abdoulaye Konaté, who presents two huge textile works from his Butterfly series. He brings a painterly eye to these quasi-abstract works that depict the vague outline of a butterfly in infinite gradations of color that he selects with absolute precision. The fabrics are raw or dyed Malian cloth and the colors are taken from the artist’s environment: the indigo blues from the semi-nomadic Tuareg people in the north-east of Mali, a different family of blues from the color of water and the River Niger, white from the Malian Arabs, reds from the soil of the earth. In this way, Konaté aesthetically translates the world around him into visual form – here, that of a fragile butterfly which he relates to the fragility of Africa’s postcolonial nations.

<figcaption> Abdoulaye Konate, Le Papillon Bleu (2016), Installation shot from EVA International – Ireland’s Biennial, 2016, Photo Miriam O’Connor, Courtesy the artist, Blain|Southern and EVA International - Ireland’s Biennial, Still (the) Barbarians, Limerick City, Ireland, 16 April – 17 July 2016, www.eva.ie

Like many art works in this thought-provoking show, Konate’s textile works communicate on many levels, but exactly how they fit in the conceptual frame of the biennale is not so easily assumed. The lack of descriptions of the art objects doesn’t make it any easier, and while this forces the viewer to confront the works before resorting to a text as mediation, some sort of clarification is often needed to arrive at any kind of interpretation – and indeed, this is what I heard some visitors complain about.

However, it is precisely this rich and divergent mixture of works – a rather idiosyncratic choice that is probably partly born from Kouoh’s African attachments as well as from her international connections – that makes for a stimulating show. These artists are way beyond waiting for any barbarians: they have recognised them/us and are already engaging them creatively and productively.

.

.

The exhibitionStill (the) Barbarians, the third EVA International Biennale in Limerick, is running until 7th July.

See more installation shots of the exhibitionhere on Contemporary And

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission