Notre auteur Elsa Guily rencontra Bouchra Khalili pour parler de son film Living Labour.

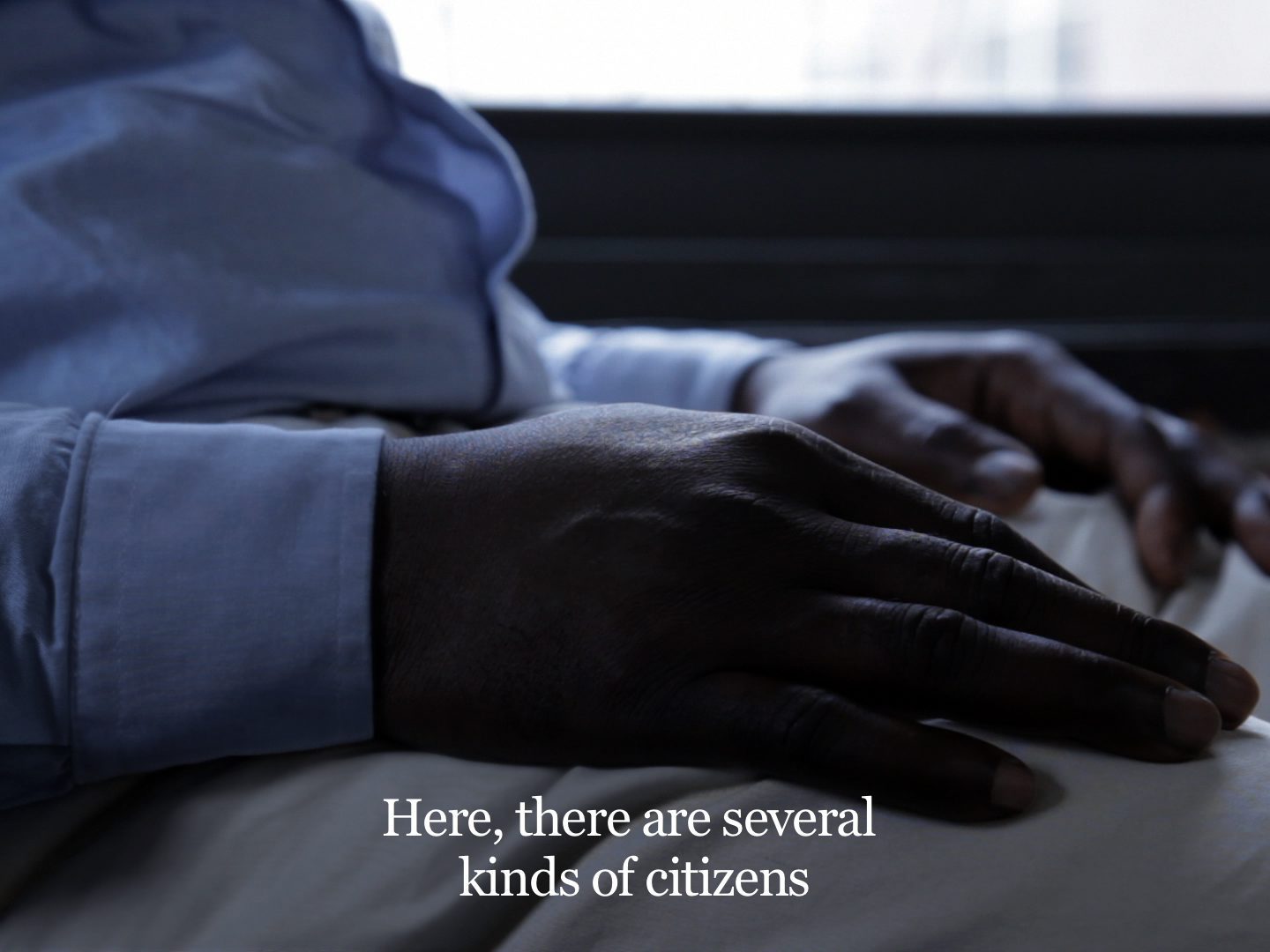

Bouchra Khalili, Speeches-Chapter 3: Living Labour, 2013. Digital film. From The Speeches Series, a video trilogy. Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Dans le film « Living Labour » – présenté lors de la 6e Biennale de Marrakech -, Bouchra Khalili s’interroge sur l’énonciation d’une parole comme geste de résistance. Articulée entre poétique et politique, son œuvre nous questionne sur le rôle des subjectivités dans la revendication d’une communauté égalitaire.

.

Elsa Guily : « Living Labour » est le dernier chapitre d’une trilogie intitulée « The Speeches Series 2012-2013 ». Pouvez-vous nous en dire plus sur la conception thématique et les étapes de la réalisation, ainsi que sur les enjeux de diffusion de ce travail ?

Bouchera Khalili : Ma pratique s’articule autour de la vidéo, l’installation, la photographie et la sérigraphie. Mes films reposent sur des dispositifs de prise de parole depuis laquelle une position singulière se représente elle-même. Dans le cas de Living Labour, chacun des protagonistes a écrit son texte, puis l’a mémorisé avant de le performer devant la caméra. La performance devient alors l’expression d’une parole subjective distanciée qui, paradoxalement, permet l’émergence d’une parole publique et collective. C’est précisément le projet de Living Labour et « The Speeches Series » (2012-2013) : une représentation de la parole par ceux qui l’énoncent, une interrogation d’une conception politique et poétique de l’identité, hors des cadres restrictifs de l’État-nation. Dès lors, la question de la diffusion se pose davantage dans ces termes : est-ce qu’un lieu d’art (musée, centre d’art, etc.) peut articuler un espace civique, poétique et esthétique ? Je le crois, de la même manière qu’une œuvre d’art est aussi en puissance un espace poétique et un espace civique.

.

Bouchra Khalili, Speeches-Chapter 3: Living Labour, 2013. Digital film, 25. From The Speeches Series, a video trilogy. Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

.

EG : La première image de chaque portrait est un plan fixe d’un espace, comme une tentative de mise en contexte de chaque parole dans un environnement social et urbain. Que viennent nous dire ces plans-séquences de la relation de l’individu au collectif dans la sphère publique ?

BK : Chaque film de la trilogie « The Speeches Series » est conçu autour d’un découpage très précis. Dans Living Labour, la parole commence par résonner dans un espace public qui appartient au quotidien de chacun des protagonistes. On voit ensuite que les protagonistes se trouvent physiquement dans un cadre qui articule intérieur et extérieur : soit une fenêtre qui ouvre vers le dehors, soit un espace entre l’espace intime et l’espace public. C’est cet entre-deux qui articule la subjectivité et le collectif.

EG : La parole trouve une place centrale dans votre œuvre, comme une possibilité pour les travailleurs que vous mettez à l’écran d’incarner leur propre récit d’autodétermination et de définition en tant qu’identité propre. Dans quelle mesure cette mise en valeur du récit trouve-t-elle son ancrage dans la tradition de la poésie civile du mouvement afro-américain des droits civiques des années 1960 à 1970 aux États-Unis et/ou d’autres traditions révolutionnaires/activistes ?

BK : Dans mes œuvres vidéo, la parole a une fonction esthétique précise, elle ne se réduit pas au sens. Il y a un écart entre ce qui est visible et ce qui est suscité par le son et le récit, bien que son et image soient simultanés l’un à l’autre. C’est dans cette tension dialectique que le spectateur prend une part active au dispositif. Les protagonistes de Living Labour se présentent – avec leur subjectivité – au public, pour poser à chacun la question d’une appartenance citoyenne. Mahoma, qui travaille sans papiers à New York, le dit littéralement dans Living Labour : « Je suis un citoyen parce que ma conscience a grandi ici. » C’est la lutte qu’il a entamé pour ses droits qui définit son appartenance citoyenne. Tous les protagonistes du film sont donc effectivement des poètes civils, mais au sens où le poète et cinéaste Pier Paolo Pasolini a renouvelé cette vieille tradition italienne. Dans Une Vitalité désespérée, il appelle à la résistance poétique et civique « en jetant son corps dans la lutte ». Mais la référence à Pasolini n’a rien de fortuit. Elle renvoie également à sa proposition d’un cinéma de poésie pensée à partir de ce qu’il avait défini comme « discours indirect libre », qui articule organiquement des voix et des points de vue multiples.

.

Bouchra Khalili, Speeches-Chapter 3: Living Labour, 2013. Digital film. From The Speeches Series, a video trilogy. Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

.

EG : Envisagez-vous l’installation multimédia-vidéo dans le champ de l’art contemporain (mondialisé) comme un support tangible pour soutenir les luttes sociales, les stratégies et les discours de résistances collectives ?

BK : Si j’ai un attachement au film et à l’installation vidéo, c’est parce que mon premier lien avec les formes artistiques vient du cinéma et de la littérature, même si j’ai commencé ma pratique artistique par la photographie. J’ignore si mon travail sera vu, compris et accepté, mais je tente de faire de l’espace d’exposition un espace poétique et civique.

.

Elsa Guily est étudiante en histoire de l’art et critique culturelle indépendante vivant à Berlin, spécialisée dans les lectures contemporaines de la théorie critique et les enjeux politiques de la représentation.

More Editorial