Narratives are everything for me

C& talks to Kitso Lynn Lelliott, participating artist of the Kampala Art Biennale 2016: Seven Hills. . C&: Tell us a bit about your artistic journey. When and how did it all start? Kitso Lynn Lelliott: Making art? It has been something I have taken for granted as it’s always been there, as a sort of …

C& talks toKitso Lynn Lelliott, participating artist ofthe Kampala Art Biennale 2016: Seven Hills.

.

C&: Tell us a bit about your artistic journey. When and how did it all start?

Kitso Lynn Lelliott: Making art? It has been something I have taken for granted as it’s always been there, as a sort of default thing that has been part of my life. I don’t know if I would say there was a 'beginning' per se but I always remember a class I had in preschool or my early years in school when a teacher we had told us a fairy tale and simultaneously illustrated it with multicolored chalk as she spoke. I was transported, transfixed, captured. It was magic right before my eyes. The love affair has been strong ever since. With age you sort of come to appreciate the gravitas of what is going on in the creative enunciation or any enunciation for that matter; that saying something is like literally making an idea come alive. So now I spend my life telling stories in one form or another so they can have a place amongst the narratives that surround us as they shape our imaginings, beliefs, and ideas.

.

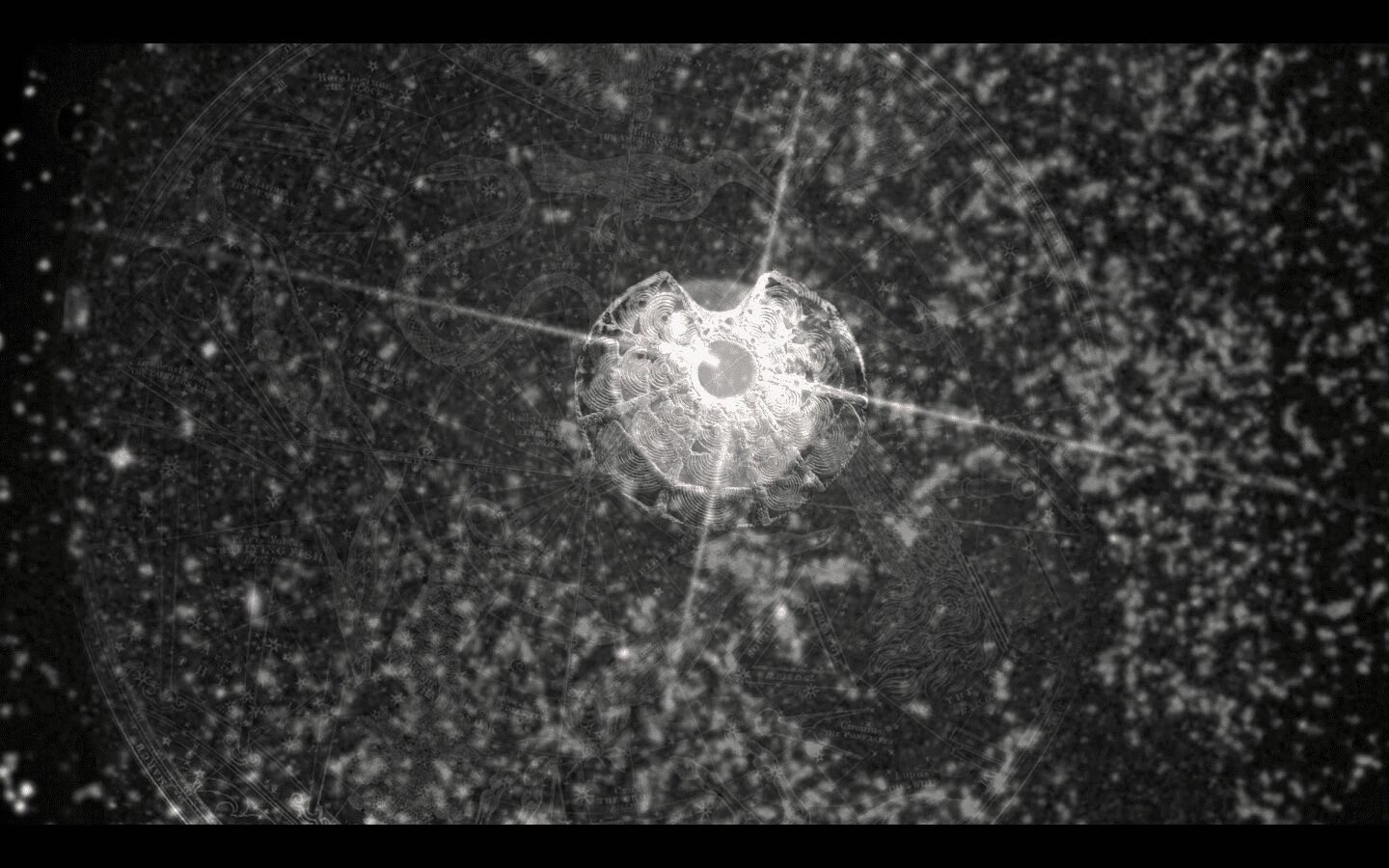

<figcaption> Kitso Lynn Elliott, Untitled, Sankofa 1, 2016. Video still. Courtesy of the artist

.

C&: How important are knowledge and learning to you?

KLL: They are key pivots in my life in general and in my practice. I am doing a PhD, and being an artist and filmmaker, people always seem to be confused as to why I would bother if I am not planning a career in academia. But for me, my academic work is key to my creative work and vice versa. They grow out of each other and enrich one another. It really boils down to the ways of thinking and questioning that come out of each and being able to push past the limits of each where the tool set from one space starts interfering with the other. So I learn through both forms of work simultaneously and in conversation while my mutual reliance on them both allows for interruptions of the boundaries set up around each one. It allows for different but entangled modes of producing and enunciating knowledge in a way that reflects my interests in trans-epistemological relations. My academic work is about knowledge and knowledge hierarchies and how knowledge coming from particular epistemologies and produced by certain kinds of bodies being privileged plays into the ways race is produced and operates. So my interest in knowing, how we come to know, what informs the ways in which we perceive and know, is about both learning how the above operates, which has lead me to start picking at the philosophical underpinnings of the structures that shape our lives, experiences, and to start interfering with the narratives that inform what we take for granted.

.

<figcaption> Kitso Lynn Elliott, My story, no doubt, is me/older than me, 2015. Video still. Courtesy of the artist

C&: You did a residency in Salvador de Bahia a few years ago. How has this affected your personal life and your artistic practice?

KLL: This particular residency was really significant for me. I had just completed my MFA and had never been away from my home region on my own for a longer period of time. It was a sort of 'deer caught in the headlights' moment. Whenever I had travelled away from home, I had always found myself in the minority in a starkly different place, where I could feel how I became peculiar, framed as some exotic other. Though I still felt some level of being 'other' and very foreign in Bahia, travelling so far away from the continent to a place that was completely alien and at the same time finding myself in a place that felt so familiar, so close yet so different was intriguing. It was strange and exhilarating as well as being profoundly depressing all at the same time. Living in South Africa for so long, you understand what segregation looks and feels like and how historical segregation really sets a society into a particular form that the present struggles to break out of. Bahia was kind of this off-mirroring experience for me with this uncanny familiarity about it. Being there, I could see how the social structure still dictated such dire living conditions for Black people as a result of historical precursors and the subsequent structural organization of capital, means, worth, value, and access as per the resulting hegemony. And that is not to imply any homogenized notion of uniformity that flattens out difference in Black experience, but rather to point to the familiarity and the stakes we have in common across all that difference. So the experience really shifted my conception of what it is to be Black in the world and offered me a sense of affinity, with this foreign place and alien familiarity I encountered there. My practice has been shaped by this ever since.

C&:Last year you took part in the Encounters of Bamako, the African Biennale of Photography and presented your work By and By Some Trace Remains. Looking at this work and other works, much of it seems to revolve around memory, oppression/trauma and collective narratives. In which way is this a way for you to tell stories?

KLL: Well, narratives are everything for me. They shape everything, the world is what it is to us, people are who they are, what is what it is through the mediation of narratives. They shape how we come to encounter, how we see and come to understand and make sense of what is. Like being Black is not anything in particular until you come to understand Blackness through all the narratives that surround Blackness and thus construct it in a particular form in relation to other things, other constructs, such as whiteness. They are all produced through the narratives we construct around them. And those narratives, beliefs and ways of seeing the world have very real, tangible effects on experiences produced through them. So in my practice I work on narratives and positioning myself deliberately in conversation and in relation so as to allude to the always partial nature of narratives, towards denying totalizing narratives that elide difference. In that way a narrative takes form and is produced according to the positionality of whoever is enunciating. Enunciating amongst a collective of voices amplifies and augments what you say, giving it resonance while also highlighting this positionality and partiality. I speak from within a collectivity of Black experience, and because Blackness as a concept/construct has been forged through trauma and produced as a space of ontological lack, I work to shift the narratives that shape Blackness in this way. I address how the stories are produced and also attempt to work around them, reshape them, offer difference from a place that does not take dominant narratives for granted as absolutes but rather as constructs that are malleable.

.

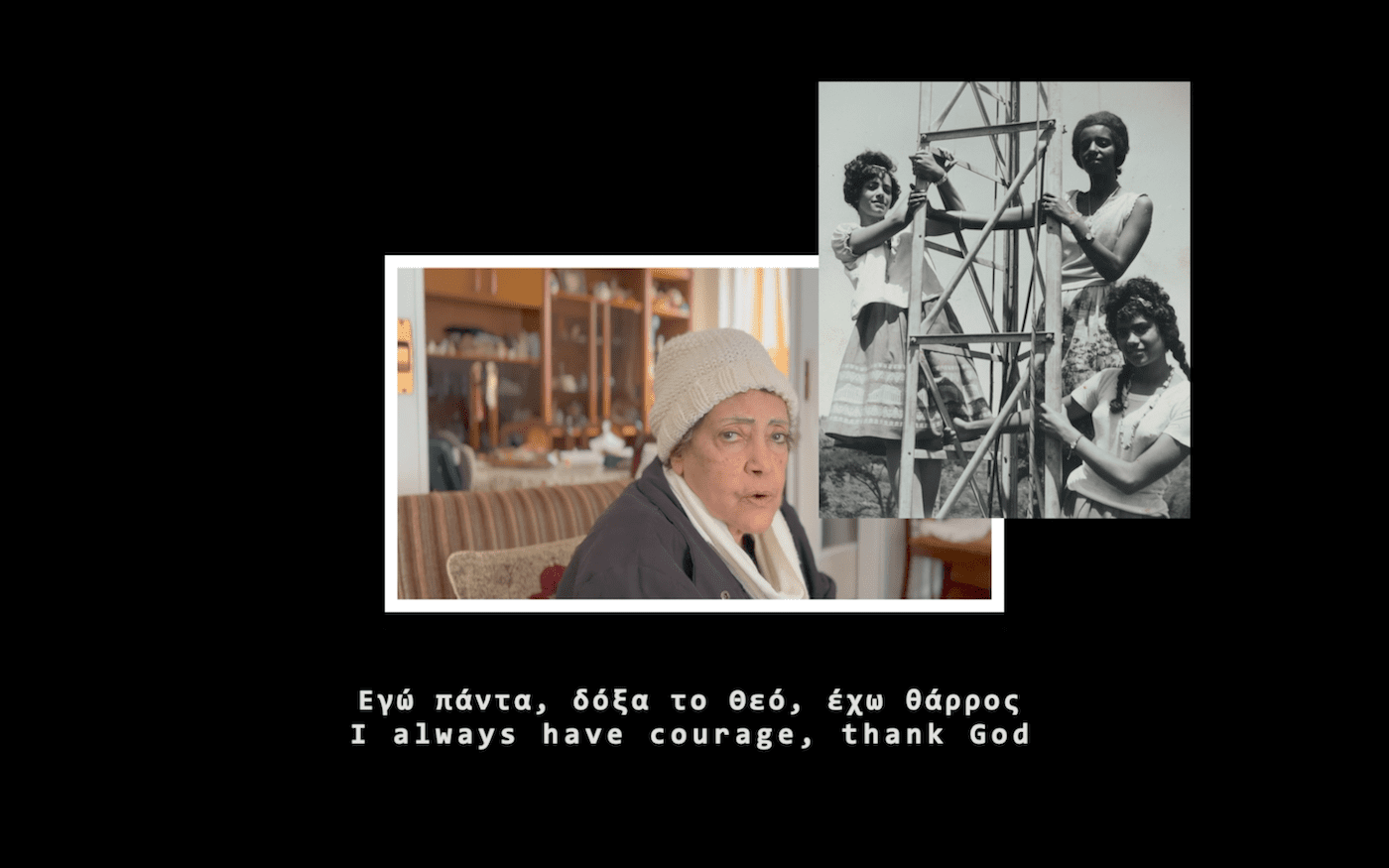

<figcaption> Kitso Lynn Elliott, I was her and she was me and those we might become, 2016. Video still. Courtesy of the artist

C&: Can you tell us about the work you are presenting at this year’s Kampala Art Biennale?

KLL: The installation in Kampala is a continuation of this work, it is one articulation amongts many articulations, my own and of others, that speaks to the difference I describe above. It is a video-based installation that is comprised of three videos, one is a pre-existing work I produced last year while on residency in Ghana, and the second two that complete and compliment it have been produced especially for this installation. I tend to use repetition in my installations in this way, where older elements come into new pieces and generate a conversation between my different works, which are actually just different permutations of articulating around the broader 'controlling' preoccupations I have. So there is this open, fluid relation quality happening between the various installations I have staged, where some trace of each gets pulled through to other spaces, creating this simultaneity and side-by-side-ness across time and related but diverse geographies.

The ‘Seven Hills’ of the Kampala Art Biennale theme have, for me, a resonance with a conception of deep time, a time of multiple histories that overlap, contest each other but are ultimately intertwined as co-producers of what has come to shape Kampala as a place. There is the time of the post-colonial, the time of the colonial, a time of a decolonial contestation as old as the colonial itself, a much deeper and longer time since the pre-colonial that runs through them, and, enveloping them all, is a geological time of the earth – the hills that have been witness to all the comings and goings, shifts and upheavals – that have shaped the space, over time, into a place. They are layered upon each other to become palimpsests on a site that has been the constant present.

.

.

Interview by Aïcha Diallo

Interdisciplinary

36th Bienal de São Paulo Reveals Title, Concept, Partnerships, and Visual Identity

Agape Harmani: Trauma as an Essential Part of Diaspora

South Africa Pavilion Announces Curator, Artists and Exhibition Title for Venice Biennale 2024

Kampala

Kampala Calling: The African and Diaspora Artists Flocking to Uganda

An Exhibition that Welcomed Grief at the Door and Pulled out a Chair