He has been known as a cinematographer for decades, but he never shared his photographs. Until last year. So now EMMY award winning artist John Simmons talks to C& about personal decisions in his photographic practice, about timing, and the purpose of art.

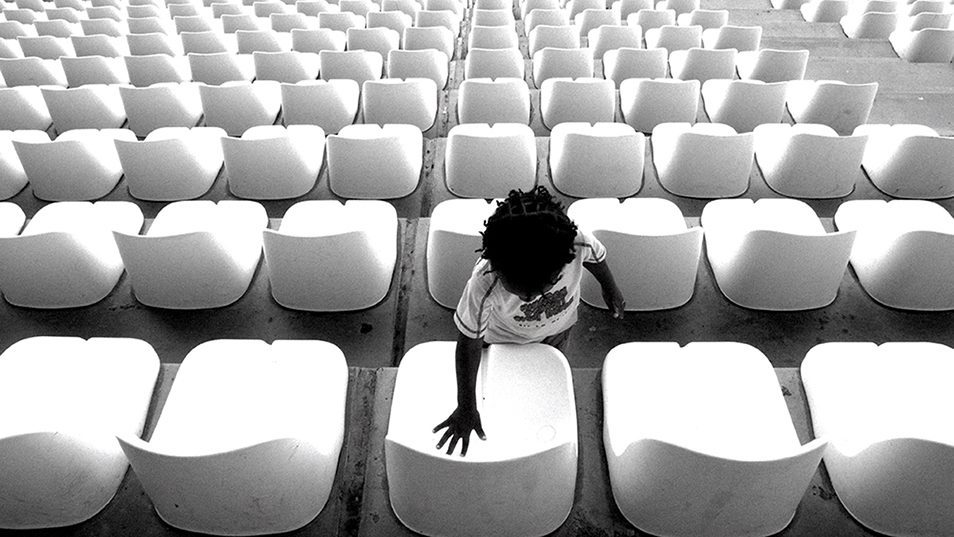

John Simmons, Checking Teeth, Trindad 2005. Copyrigth John Simmons, ASC.

Magnus Rosengarten: You’re mainly known as a cinematographer. How would you characterize the medium?

John Simmons: Cinematography is usually a narrative that has been agreed upon by many people, whether it is a commercial, TV show or sitcom. There’s a look that has been agreed upon, there’s a pace, there’s a palette.

MR: But doesn’t that also apply to photography these days?

JS: I absolutely agree. But my photography isn’t like that. My photography speaks a completely different language. There’s nobody who tells me how or when to press the shutter. It’s all about decisions that I make and that come from my heart or come from the events that I see taking place before me. With the moving image there’s also a continuum, there’s montage that holds everything together and in photography –not to be cliché– you’re dealing with the decisive moment.

MR: You also said that the moving image is about narrative. Could you elaborate on that?

JS: With my photography, there’s no pre-planning. There are things that take place in front of me. These things and I converge with each other and I take the picture. When I take pictures I almost want it to be symbolic in that it takes you beyond the concrete image of what you see and takes you to another realm where you wonder what exists beyond that frame. What was actually taking place at that moment? I want to be able to produce those kinds of questions, both for me and the viewer. The other day I was on Hollywood Boulevard around 11 o’clock at night and took a picture of a homeless guy dressed up as Superman who was sitting on some steps with a little boy and two other adults looking at him. It’s a crazy photograph. How did all these elements come together at the same time to be able to tell that story? It always blows my mind.

MR: Yes, it almost sounds like a transcendental experience…

JS: Exactly, transcendence is the word. I feel like a picture is almost not worth hanging on the wall unless it has that element of transcendence, that power to think beyond the frame. Imagine you just had one photograph in your house or in a room: is that one photograph strong enough to carry the wall? Instead of making an exhibit, imagine your friends walking in and seeing that one picture. Would they still be satisfied?

MR: Is there a relationship between ritual and work? And how would you describe it?

JS: Well, when we talk about ritual in terms of the exhibit, we’re basically talking about how people have come to live through habit. And the foundation lies in wherever they come from. Take Black people and our tradition and life that we brought to America and the life that was left. But also the elements that remain, like the sanctified church, the protests, the dancing you see, or the cooking. I am talking about the everyday occurrences that carry us into an environment that has created a culture for us to be identified with. I’m saying this in the most optimistic sense: Everyone wants to be able to think about a certain kind of love that we have for the things we do. In the broader sense this is what humanity is. Unfortunately, when you talk about people being locked in a certain perspective, it’s a problem because it is not embracing. Yet that describes the political situation we’re in right now, globally.

MR: What is the advice you would pass on to young and upcoming artists?

JS: The most valuable lesson I learned is that everyone wants the same thing. Everyone wants to live, everyone wants to experience the life they dream of, everyone wants to experience a connectedness to other people and everyone wants to be a part of the fabric of life and push that forward. People want to be informed, they want artists to share their perspective, their perception. I think photographic work should have a certain foundation to it, a certain substance to it. It should have a purpose in terms of what it does to someone. A lot of works in the exhibition Time Light and Ritual that I set up with my friend Frank Stewart depict such insignificant moments. There’s a photograph of a girl drawing a picture on a frosted window of a restaurant, and I guess it is her father looking at her and he is smiling at what she is doing. People absolutely love that picture. The only thing that picture talks about is that moment of affection.

Magnus Rosengarten is a writer and artist based in New York.

More Editorial