Metaphors for Humanity

Contemporary And: What is your show Ruins Decorated about? Yinka Shonibare MBE: The show is about the end of something and the beginning of something else. It is about the end of the British and Roman empires, which brought the possibility of rebirth. And it is about the fall of imperialism, which also brought the …

Contemporary And: What is your show Ruins Decorated about?

Yinka Shonibare MBE: The show is about the end of something and the beginning of something else. It is about the end of the British and Roman empires, which brought the possibility of rebirth. And it is about the fall of imperialism, which also brought the opportunity of creating a new world. From those horrible legacies and destructions, we make new things. The show is about relooking at the myth of superiority that has, for a very long time, been promoted through culture – sculptures, images, and the likes – and finding new ways of deconstructing these myths and creating a new world.

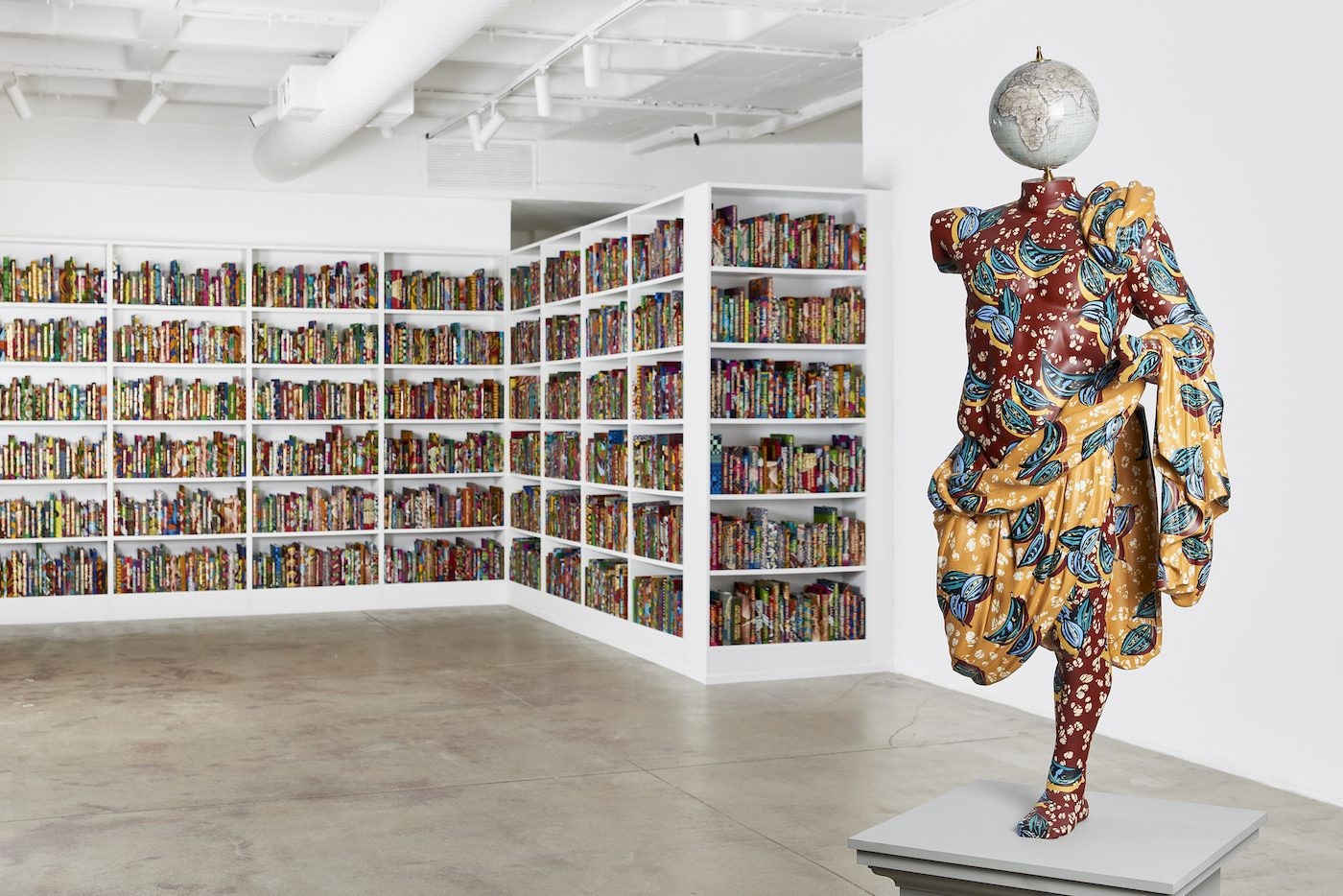

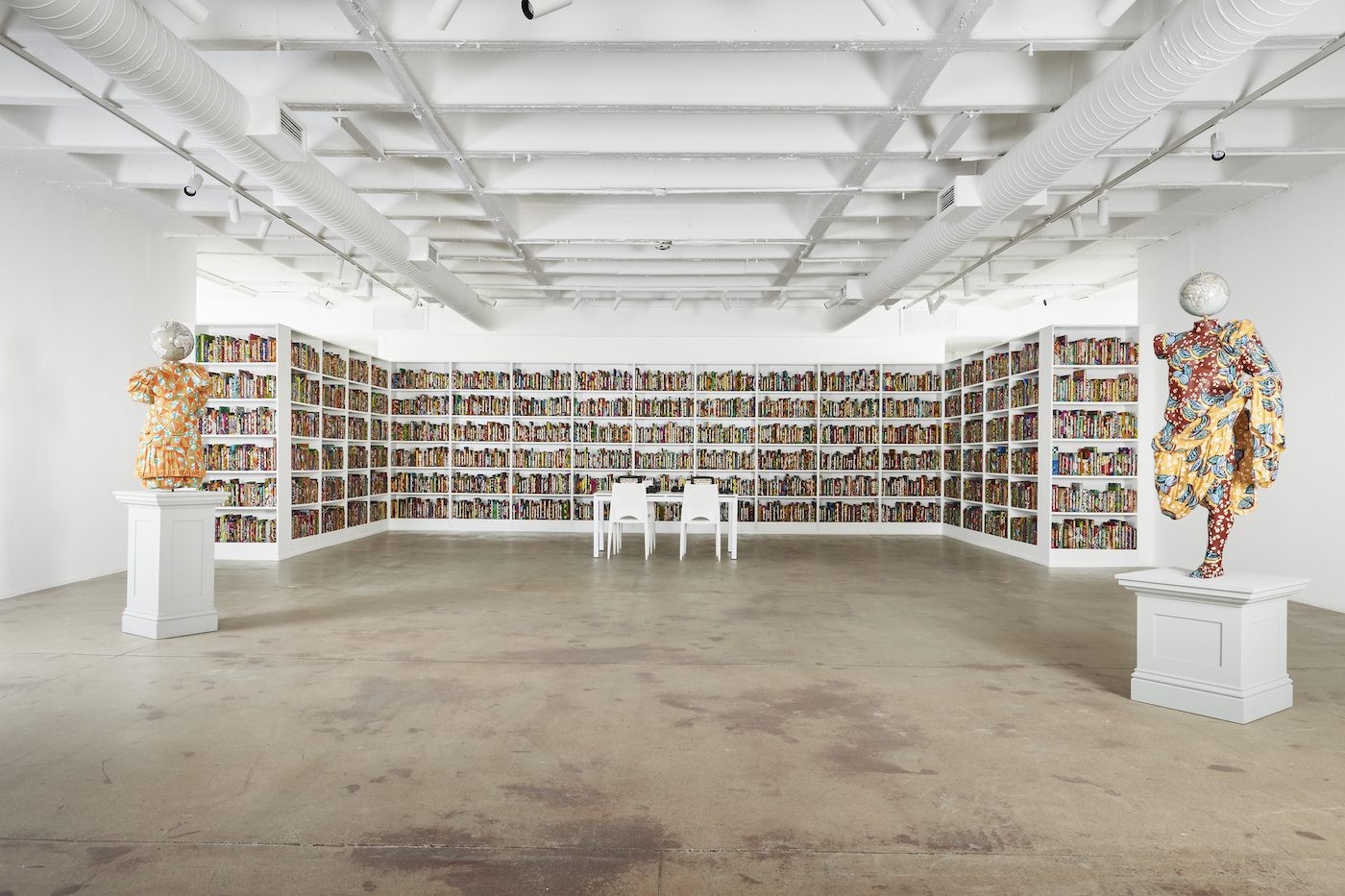

Installation view of Ruins Decorated by Yinka Shonibare MBE at Goodman Gallery Johannesburg, 2018. Courtesy Goodman Gallery.

C&: Author Teju Cole, in his collection of essays Known and Stranger Things (2016), speaks of the idea of owning culture. Is this what you aim for with your work – the questioning, inverting, and merging of different cultures?

YSM: In a way, yes. I don’t believe in essentialism. If you’re not careful, you could end up looking like the fascists. The world is a complex place and we find ourselves where we are now because of history – which you cannot erase. You can’t promote isolation. Not recognizing history and different cultures created from that history is a form of myth.

C&: Maybe it is because of this complexity that you work with mixed media – sculpture, photography, film, and installation. One of the main parts in your current exhibition is The African Library installation. What was the process of accumulating all those names and all those stories?

YSM: It was a complicated process that required assistance from scholars and researchers – there are roughly 3000 names. The library is about Africans who have made significant contributions to different areas of culture, from the arts to science and politics. It is an African empowerment library.

Yinka Shonibare MBE, Clementia, 2018. Fibreglass sculpture, hand-painted with Batik pattern, and steelbase plate or plinth, Figure: 143.5 x 81 x 53 cm. Plinth: 70 x 90 x 70 cm Unique. Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery

C&: You’ve also challenged the complexity of fabrics in the exhibition. Dutch wax-print cotton in particular prompted questions about where it comes from and what it represents. How do you choose to use this kind of material in your work?

YSM: When I was growing up in Nigeria, I saw those fabrics everywhere and believed they were “authentically African.” It came as a surprise when I found out they were Indonesian-influenced fabrics produced by the Dutch and sold to West Africans. I thought that was very interesting – the assumptions and unacknowledged narratives surrounding the material. Racism itself is based on assumptions; people’s biographies have various levels of complexity and racism tries to find a way to ignore those complexities. The fabric and its history form a good metaphor for exploring some of the standard stereotypes around Africans. I’m attempting to look deeper into what it is that things actually signify.

Installation view of Ruins Decorated by Yinka Shonibare MBE at Goodman Gallery Johannesburg, 2018. Courtesy Goodman Gallery.

C&: You’re covering some of your sculptures in Dutch fabric, and in that context you speak about “the decoration of power in the wrong colors.” What do you mean exactly?

YSM: A white supremacist using white marble as the ideal sculpture material might find the Dutch wax-print cottons covering them to be of the wrong colors. For me, it’s about the “wrong colors” in inverted commas: injustice, discrimination, racism, unemployment, ghettos, economic exclusion of black people, African Americans getting killed on the streets. Unfairness. The list goes on and on and on.

C&: Your sculptures have very diverse heads – some human, some animal, and some clearly objects. What informed these choices?

YSM: They started off as a joke about the French Revolution, when the aristocracy had their heads chopped off. But as time went on, the approach changed. I wanted to acknowledge diversity. A lot of the problems in the world right now can be traced to discrimination and refusals to acknowledge diversity. And in this way a lot of talent and contributions are lost. The heads are no longer a particular race, they are all cultures – a metaphor for humanity.

Yinka Shonibare MBE was born 1962 in London and lives and works there. He moved to Lagos at the age of three and returned to London to study Fine Art at Byam Shaw School of Art (now Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design) and at Goldsmiths College, where he received his MFA, graduating as part of the ‘Young British Artists’ generation. Shonibare was a Turner prize nominee in 2004 and awarded the decoration of Member of the “Most Excellent Order of the British Empire”.

Nkgopoleng Moloi is a photographer & art writer focusing on contemporary visual art from the continent & diaspora. She’s passionate about history, storytelling & understanding how people navigate space through time.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas