Kehinde Wiley on the Flat Screen

16 February 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

5 min read

. If you haven’t been living under a rock the past two years, then you’ve probably heard of Empire. The American hip-hop drama has taken the world by storm since it first graced the small screen back in 2015. With tracks produced by legendary recording heavyweight Timbaland, it’s easy to overlook the vast array of contemporary art …

.

If you haven’t been living under a rock the past two years, then you’ve probably heard of Empire. The American hip-hop drama has taken the world by storm since it first graced the small screen back in 2015. With tracks produced by legendary recording heavyweight Timbaland, it’s easy to overlook the vast array of contemporary art featured silently in the background. And while the soundtrack’s searing bass and catchy hooks go hand in hand with the sassy dialogue and quick-witted exchanges, the art hangs boldly in the periphery of all the most memorable scenes. Strung above mantelpieces and confidently asserting authority even over the characters portrayed by Terrence Howard and Taraji P. Henson themselves, the art is also showcasing its own powerful parallel narrative on race, class, and the changing ownership of fine art in popular culture today.

Howard graduateJamea Richmond-Edwards stands out with her painting Wings Not Meant to Fly as a central piece in the living room set of the show. The bold, rich colors ofMichael Savoie’s Natural are as memorable as Cookie’s outfit, when she is standing right next to it. Basquiat, a notorious influence on Jay Z’s love affair with contemporary art appears several times throughout season one, and the Jugendstil master himself, Gustav Klimt, lends his grandiosity to the series with his famed Art Nouveau masterpiece,Hygieia.

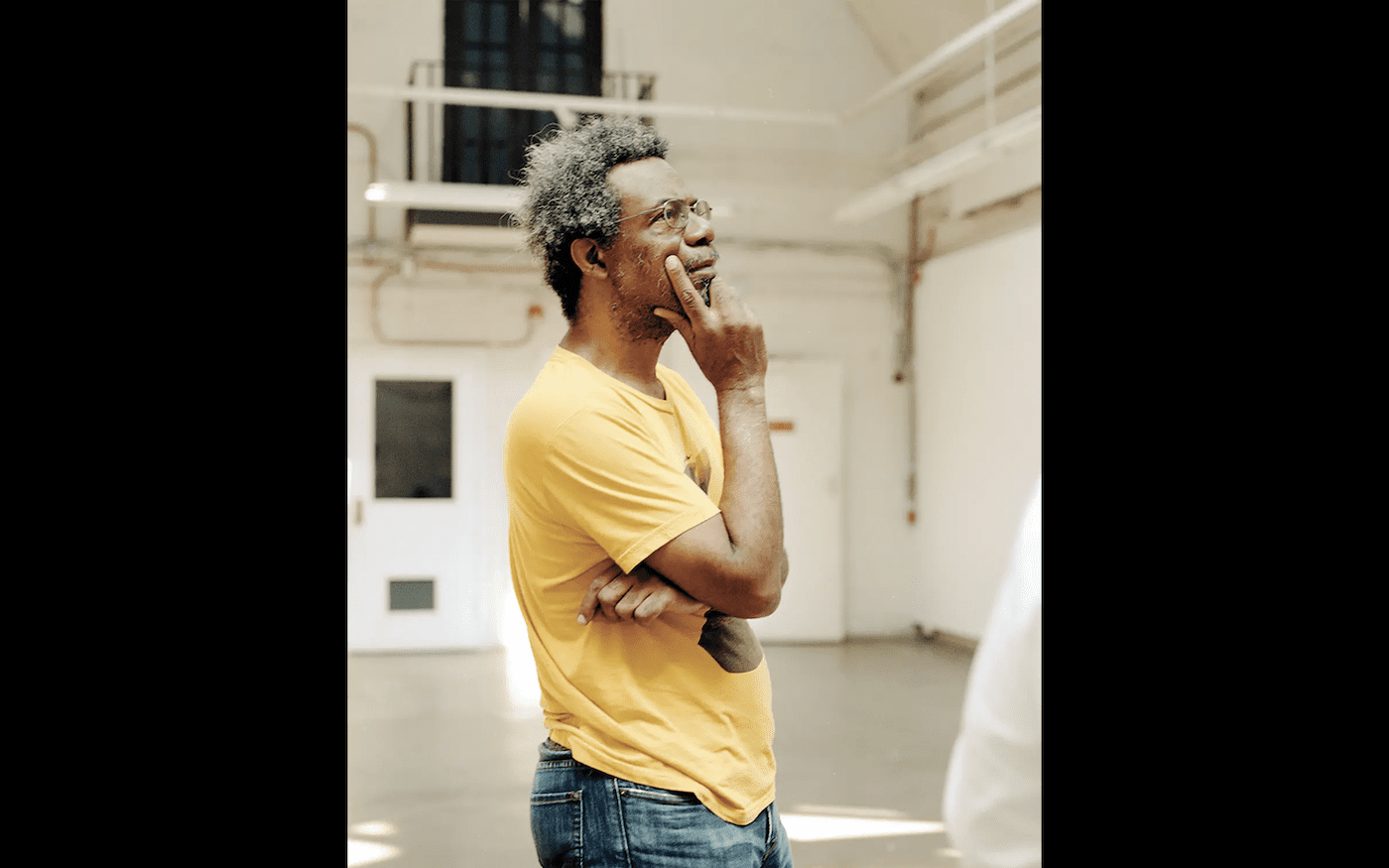

But perhaps the most noted and outspoken “breakout” artist to have their work featured in the show is New York-based portrait painter Kehinde Wiley. It’s a fitting merger, between an artist who creates the sublime out of the everyday images often denigrated in a society that privileges whiteness, and a show that puts Blackness into a fully-focused foreground in all its splendid, dramatized, stylized and emotionally complex glory.

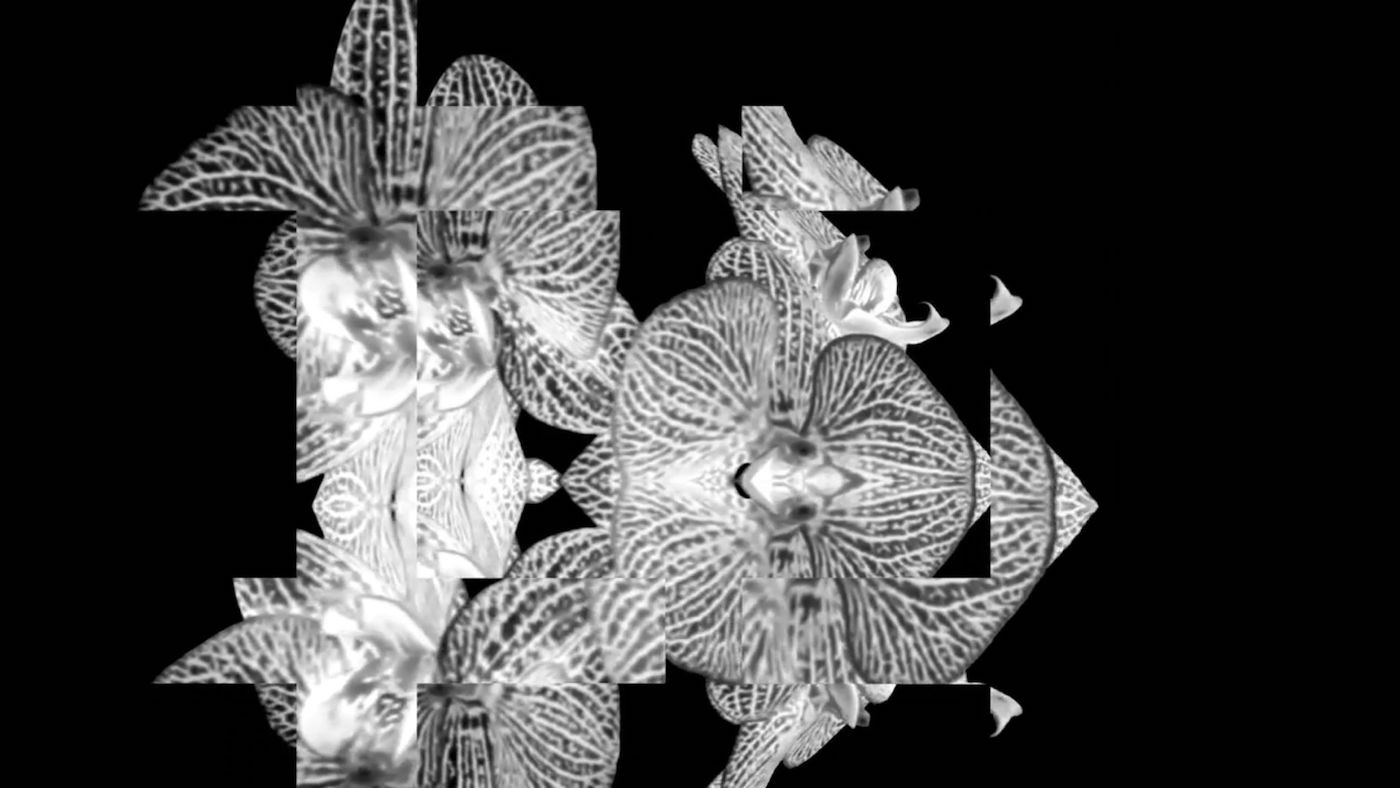

Wiley’s famously detailed, rich paintings are a visual feast for the eyes. Taking everyday images of Black men and women, he turns them into regal kings and queens of the American Diaspora – sitting astride on horseback in a pair of jeans and a singlet, as is the case in his piece Rumors of War, Officer of the Hussars; or topless and tattooed in boxers and sagging pants, as is the case in Prince Albert, Prince Consort of Queen Victoria. His portraits of men and women stand proudly against backdrops of exquisite detail reminiscent of Victorian England, but with all the depth, color and flair, uncharacteristic of the era, and which represents the very essence and style of Empire, perfectly.

The juxtaposition of the paintings against the many interwoven narratives of the Lyons’ conveys a complexity in African-American culture not often portrayed in film, television, or even music. The characters in the show are dynamic, and each showcases multiple sides to their personality in a stunning array of drama and human emotion normally reserved for white characters. Black women are powerful and ferocious, but also loving mothers and fierce partners. Black men can be proud, talented, insecure and queer. Relationships between the two are complicated and involved, relatable and entertaining. This is a far cry from the homogenous stereotyping of the past, where people of color were expected to play roles confined by stereotypes and forced social roles. A refreshing change, these performances are complemented perfectly by Wiley’s work. On his canvas, Black America is proud, fierce, intelligent, affluent, complex, cultured, three-dimensional, and bloody gorgeous.

.

https://youtu.be/gMB7uZvFCyE

.

The symbiotic relationship between fine art and Empire speaks to a change in what Wiley calls the "cultural temperature," in the way we view both Black people in America, and their access to contemporary art, a world notoriously both insular and privileged. Much of the contemporary art world evades popular culture, opting instead to showcase art in carefully curated spaces where the work can be contextualized and interpreted by minds that have been formally educated to do so. The reasoning being that the art would somehow get lost in the drama of a show like Empire, with it’s intricate plot, and various subplots. But Wiley rejects this approach as antiquated, instead embracing popular culture and its audience, who engage with his work, and contextualize it in much the same way as any spectator would in a gallery in SoHo. By featuring on television, he invites the very people who inspire his work to participate in the discussion in however way they wish. And that doesn’t diminish his work’s significance… it enhances it.

.

Jennifer Neal is a journalist and writer based in Berlin, where she is writing her first novel. Her interests lie in race, gender, politics and fine art.

Read more from

MAM São Paulo announces Diane Lima as Curator of the 39th Panorama of Brazilian Art

Naomi Beckwith Unveils Core Artistic Team for documenta 16

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo Announces List of Participants for its 36th Edition

Read more from

Faith Ringgold: “I am very inspired to tell my story, and that’s my story.”

William Pope.L (1955-2023)