Experimenting with new ideas and techniques, the artists' new bodies of work presented in this exhibition, exploring the social and architectural fabric of Lagos.

Stephen Tayo, Lagos Diva (Detail), 2020. Archival inkjet print. Courtesy the kó gallery.

In How Close Can It Get, Joseph Obanubi examines a city’s proximity to its populations and properties using digital collage and line drawings to reveal new understandings of the psychic and material densities of Africa’s most populous city – Lagos. His work is part of a group exhibition at the kó art space.

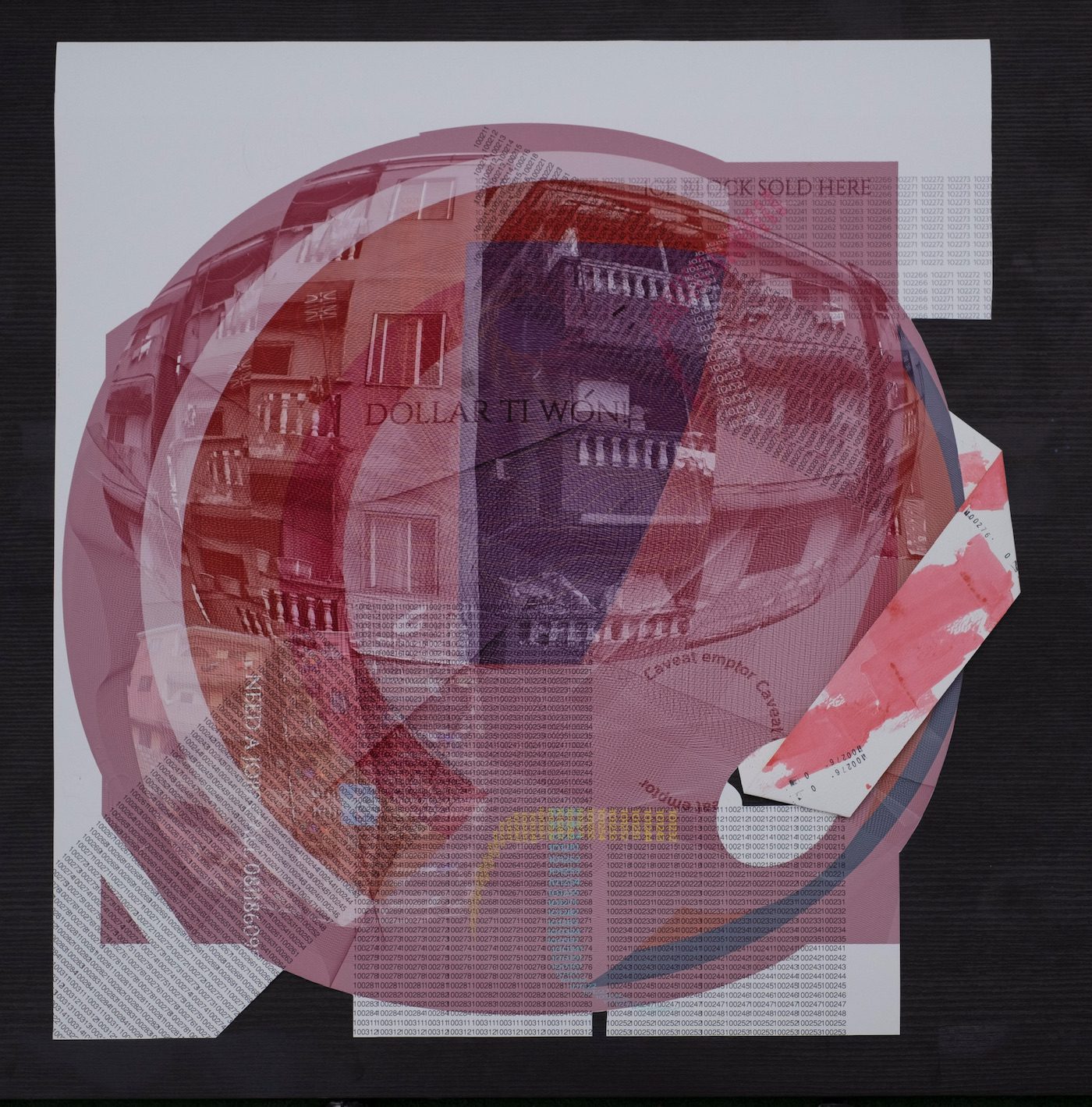

Over a period of twelve months, the artist went on periodic walks around Lagos, taking photographs of its tightly compacted buildings and visual elements that included hard-boiled maxims, posted bills, and hygiene prohibitions. Drawing color cues from the design of Nigerian Naira bills, Obanubi combined sets of disparate images into digital montages.

Joseph Obanubi, Megacity Experiment V, 2020. Digital collage, blind embossing, number stamp and ink wash. Courtesy the kó gallery.

The resulting six images, titled Mega City Experiments I – VI, offer a visual feast that requires considered viewing to be made sense of as a whole. Each image is dominated by the outer surfaces of multistory buildings that tell of city dwellers’ closely packed lives and livelihoods and other elements that do not lend themselves to easy understanding. The patient viewer could spend time parsing out each element before coming to a conclusion about the picture as a whole.

Obanubi’s stated aim is to interrogate how “people’s experiences of personal space are dictated by socioeconomic conditions and wealth inequalities.” How Close Can It Get is resolutely engaged with the excesses of big city life as it is today. But the form of collaging that Obanubi has chosen is a continuous experiment: “I am learning and exploring as I see where it leads,” he says. “That’s if there is a final destination.”

Two weeks before the opening of kó’s first group show in Lagos, photographer Stephen Tayo completely revised all the works he intended to show me for our interview. One major change was from single-image portraits to obscured multiples of each subject. “Dealing with my sensitive topics,” said Tayo “I thought it would be really nice to show the work in a careful way. To show the work with some sort of diligence.”

“Diligence” as a watchword is sustained throughout Tayo’s work What If?, an examination of drag culture in Nigeria. His decision to obscure the faces of his subjects, willing participants with whom he had developed a trusting relationship over months, seemed paramount in view of the prevailing attitudes.

In all versions of What If?, confidence and self-possession is exuded by each subject. A set of five individual portraits reveals a studied poise. Two – I Dey Low Key and Call Me Boogie – show a subject in elegant ballroom costume, faces shaded by the ring and frills of their hats, respectively. Lagos Diva cuts a dash in her half-cut dress and swinging blonde hair, whose placement on the left side of the frame activates the plain beige color field that takes up 60 percent of the inkjet print.

But the real pizzaz is saved for four works titled Na Lagos We Dey 1–4 on account of the dashing hairdos and theatrical strutting caught in mid-stride. Did Tayo stage or suggest poses for his subjects to achieve a desired result? “The uniqueness was what I was looking for and this really revolves around everyone being themselves. I was looking at the person, at the courage to be oneself in a society where even this is foreign.”

Landscape Mode is Edozie Anedu’s first foray into what he describes as “imaginative cityscape paintings.” Rather than a complete departure from his previous figurative paintings, Landscape Mode repurposes certain hallmarks of color, line, and form into critiques of urbanization in Lagos.

A great deal of color action takes place in Anedu’s paintings. The most obvious are between the few colors that make up the open skies and numerous shades and tints that distinguish the cramped buildings. In Victoria’s Redemption, the dominating bright red sky intensifies the yellows and blues that reoccur among the houses below it. But the grey and blue skies in August mute the displacements of yellows, green teals, and blacks.

Key to Landscape Mode is the very act of drawing – it is elemental and essential. A slight distinction between the adjectives is necessary to emphasize drawing’s importance to Anedu’s medium and world creation, which are drawn from badly handwritten notes and rough workings in notebooks. Drawing is called upon to explain the artist’s self-examination and self-esteem: “Drawing always shows how insecure or how bold I am. My imperfect drawings are actually beautiful if you can see it.”

Anedu may credit his experiments with color fields to Mark Rothko’s rectangular blocks but his so-called multiforms outscale the miniforms (as we shall now call them) to which the Nigerian artist has taken. Shrink these cityscape miniforms and Anedu comes closer to the near pointillism of Ablade Glover, who has long committed to the “constant exploration of that idea even if the changes are slight.”

Sabo Kpade is writer, journalist and a Fellow of Global Arts and Cultures at Rhode Island School of Design (USA). He currently writes for Contemporary And (C&). Previously, he wrote for Okay Africa, Guardian Newspaper Nigeria and Media Diversified.

More Editorial