It’s all about sharing knowledge

12 April 2016

Magazine C& Magazine

8 min read

To reach Ocean View, we followed the beautiful False Bay coastline for about an hour. I was being driven by Ciraj Rassool, who had set up this meeting with Peter Clarke, one of the leading South African artists of his generation. When Ciraj asked Peter for directions, the answer was: “Up the …

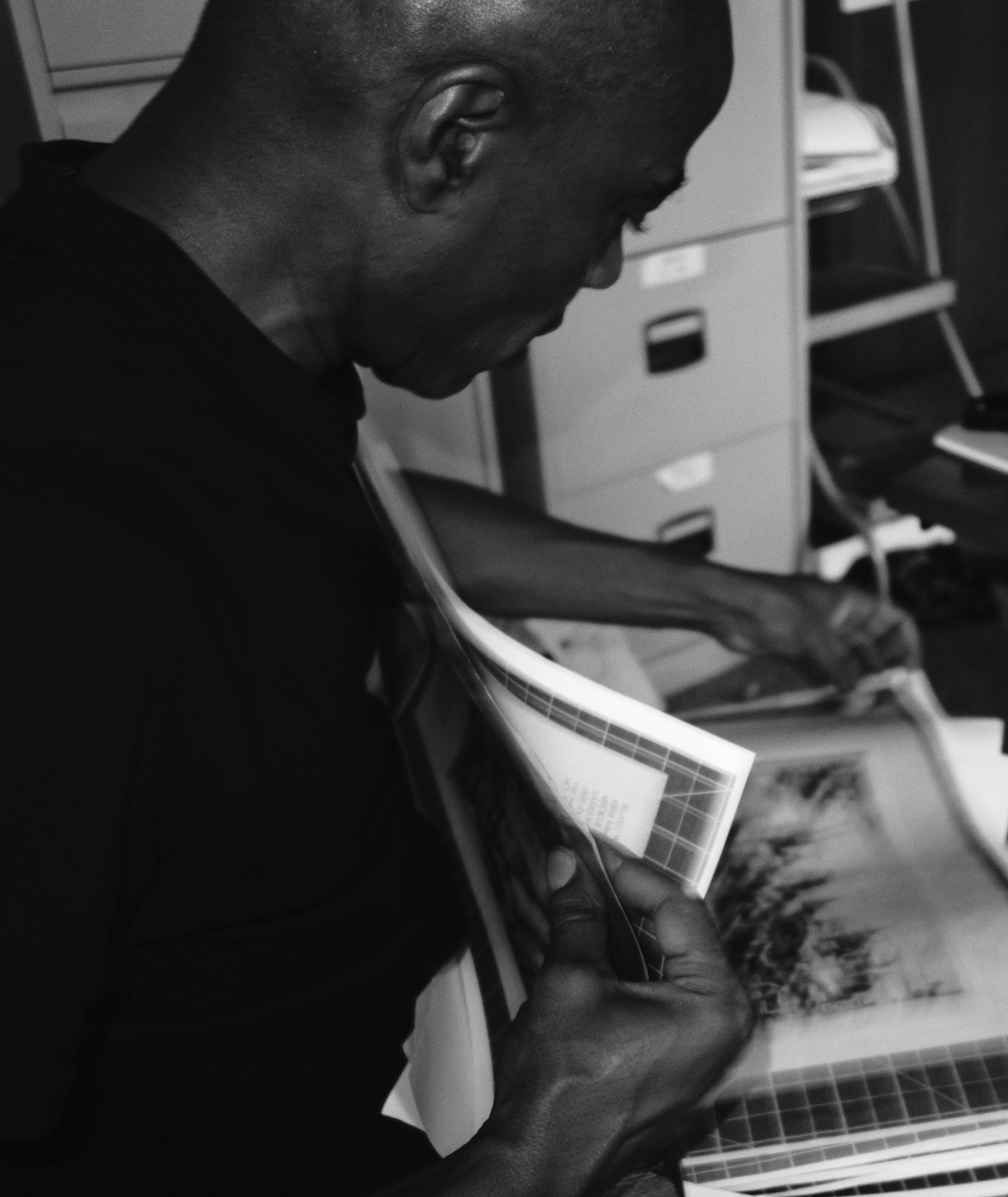

To reach Ocean View, we followed the beautiful False Bay coastline for about an hour. I was being driven by Ciraj Rassool, who had set up this meeting with Peter Clarke, one of the leading South African artists of his generation. When Ciraj asked Peter for directions, the answer was: “Up the street five glimpses behind an olive tree.” A rather poetic description, though not one that made it easy to find his house. We got there in the end, but of course we had no way of knowing this would be our last chance to talk to Peter. Sadly, he passed away just a few weeks later.

Peter had lived in this house since 1972, and no amount of fame or fortune ever made him want to leave. Yet he had not moved there voluntarily. Peter and his family had been living in Simon’s Town, but under the Group Areas Act the entire community was forced to move to Ocean View, a township in Cape Town. Unlike Simon’s Town, Ocean View is far from the coast, its name a bitter irony. But it was precisely this traumatic experience that made Peter decide to continue living in a location that was a constant reminder of what the apartheid regime had done.

We entered the small house through the front door, walking directly into a living room packed with books and art. It was a wonderful place full of memories, knowledge, poetry, and anecdotes. We sat on Peter’s sofa looking through the images of his works and those of his peers in the Weltkulturen Museum’s collection in Frankfurt. Peter had not given a thought for decades to the German pastor Hans Blum, who came to Cape Town on behalf of the museum ready to buy everything he could lay his hands on.

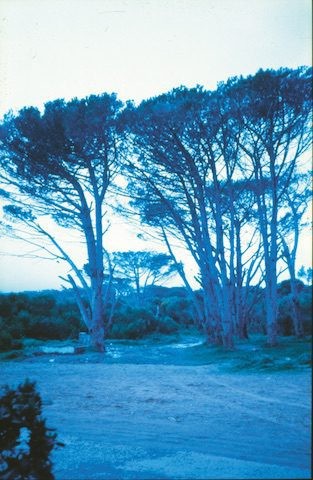

<figcaption> Ocean View, Cape Town, South Africa, 1986. Photo: Hans Blum. Courtesy of the Weltkulturen Museum

Yvette Mutumba: What was it like for you when Hans Blum came to Cape Town to collect artworks?

Peter Clarke: In later years it made me think of a white explorer wearing a pith helmet travelling to Africa saying, “I will take that, that, that, that, and that.” Somewhere in the book I’m reading right now, it talks about these two Americans who came out to collect in Africa, and they collected with such enthusiasm that they kept people busy for years producing work. I’m glad you showed me what Blum collected in South Africa, as there were works by a number of artists I knew. He used to ask: “Do you know of anybody...?” so I told him about all the other people I knew, gave him their names and addresses, and off he went.

YM: The works Hans Blum collected for the museum have given us a very special archive – a wide range of different works from a specific time and context, all produced by black artists. That’s why I think it’s important to exhibit them again and to show how collecting in the 1970s and 1980s was very different from today. Blum actually used to live and work near Rorke’s Drift, which explains his direct connection to the art world. But when he came back in 1986, Bongi Dhlomo-Mautloa acted as his mediator. It was a different age, not like today when you can do a Google search before you come here to figure out who and where people are. This is an important aspect, since today curators from whatever big museum or biennale tend to fly in, pick out some artworks, and fly back. They see what they’re doing as a good thing – which in a way it is. They feel proud of themselves for looking beyond the “West,” but this has a similar kind of feel to those ethnographic collecting expeditions from 100 years ago when Europeans would visit, stay a few days, take objects back, and that was it.

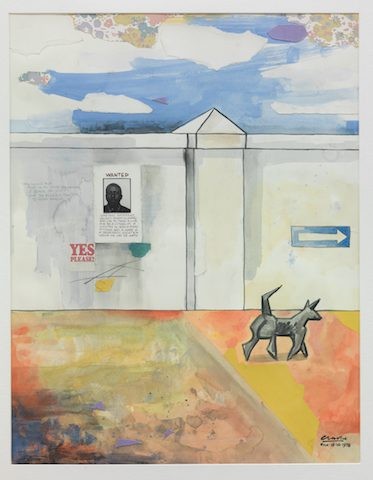

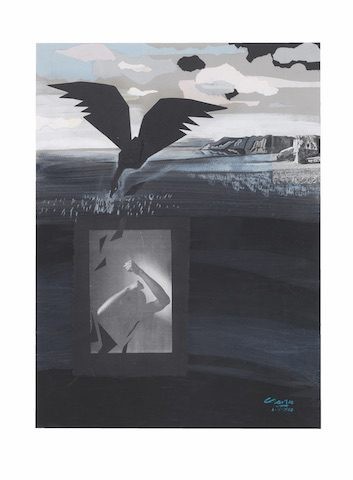

<figcaption> Peter Clarke, Wanted, 1978. Mixed Media. Courtesy of the Weltkulturen Museum

Ciraj Rassool: Express collecting.

YM: Yes. So, what I like about Hans Blum is his very real passion for this work – and that he lived here, knows the people, and has kept up this continuous dialogue from the late 1970s. Looked at from the perspective of our history, the museum’s history, it makes the collection very specific. It has the story of Hans behind it, as well as the stories of other people. Our museum’s collection has another similar yet different example of 900 works from Uganda. They were collected by a man called Jochen Schneider. He was also German and lived in Uganda in the 1960s and 1970s. He mostly collected works by students from the School of Industrial and Fine Arts at Kampala’s Makerere University. When I went there in 2013, they told me that Schneider used to come to the college every Saturday. The house technician would let him in and sell off works. Most of the students never found out their works had been sold. I showed images of the works to lecturers at the college, among them former students, and some said, “Oh, my god, that’s what happened to my work!”

CR: What’s your relationship with the works that leave you? How do you let go and how do you reconnect?

PC: It’s quite difficult... of course, artists don’t remember everything they’ve let go of. I’ve often thought that an artist’s works are very much like children. So at times when I remembered specific works, I wondered – are they being taken care of? Most owners of works develop a very particular attachment, as is only too obvious when you try and find works for a long-term event such as a retrospective. You always have to go down on very good knees to get works from people. It’s like one woman I met who asked me, “But how long will it be away?” She couldn’t make up her mind. She said, “You know, my husband and I bought this from you when we were still very young. He has since passed away, and I thought a great work of art is living proof that you have lived.”

<figcaption> Peter Clarke, Solitary confident,1980.Mixed Media. Courtesy of the Weltkulturen Museum

YM: That personal attachment to artworks is an interesting aspect, and it raises the question of what are often very personal interpretations of artworks.

PC: Interpretations are always fascinating. I have a picture of who I am, just as I’m aware of the fact that I am a certain height. But only when I see myself in a photograph next to other people do I really see how big or how small I am. Yesterday I went to this Leonardo da Vinci exhibition where one of the exhibits is a mirrored cubicle. Eight sides, eight mirrors. So when you step into this space, you see yourself reflected from all angles. It’s a strange kind of experience, almost weird. You are not just one person; you’ve become eight different people seen from different yet familiar angles. But it is strange when you read what other people write about your work. You don’t always agree with it, of course, and sometimes you are taken by surprise.

YM: But isn’t it interesting if someone is seeing something totally different from what you intended, coming from a different perspective?

PC: It is – because it’s something that you didn’t expect. There are times when you look at works of mine and it’s got nothing to do with politics or anything, but there are birds flying or something like that. That’s related to my travels, since when you travel you look at things, and to look at things is to gain knowledge. When I come back, I especially like to engage with other, younger, artists, as it’s also all about sharing knowledge.

This interview is an edited excerpt from the book A Labour of Love, edited by Yvette Mutumba and Gabi Ngcobo, Bielefeld, Germany, 2015.

Yvette Mutumba is curator at the Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt, and co-founder of C&. Mutumba studied Art History and holds a PhD from Birkbeck, University of London. She has published numerous texts and comprehensive catalogues concerning visual arts from African perspectives.

Ciraj Rassool directs the University of the Western Cape’s African Program in Museum and Heritage Studies, managed in partnership with Robben Island Museum. He has written widely on public history, visual history, and resistance historiography. He is a trustee of theDistrict Six Museum, which he co-founded in 1994, and a councilor of Iziko Museums of Cape Town.

Read more from

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

Confronting the Absence of Latin America in Conversations on African Diasporic Art

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

Read more from

MACAS amplía su colección de arte afropuertorriqueño

Negras imagens − Formação a partir do acervo IMS