‘It was African and Kabuki-like at the same time’

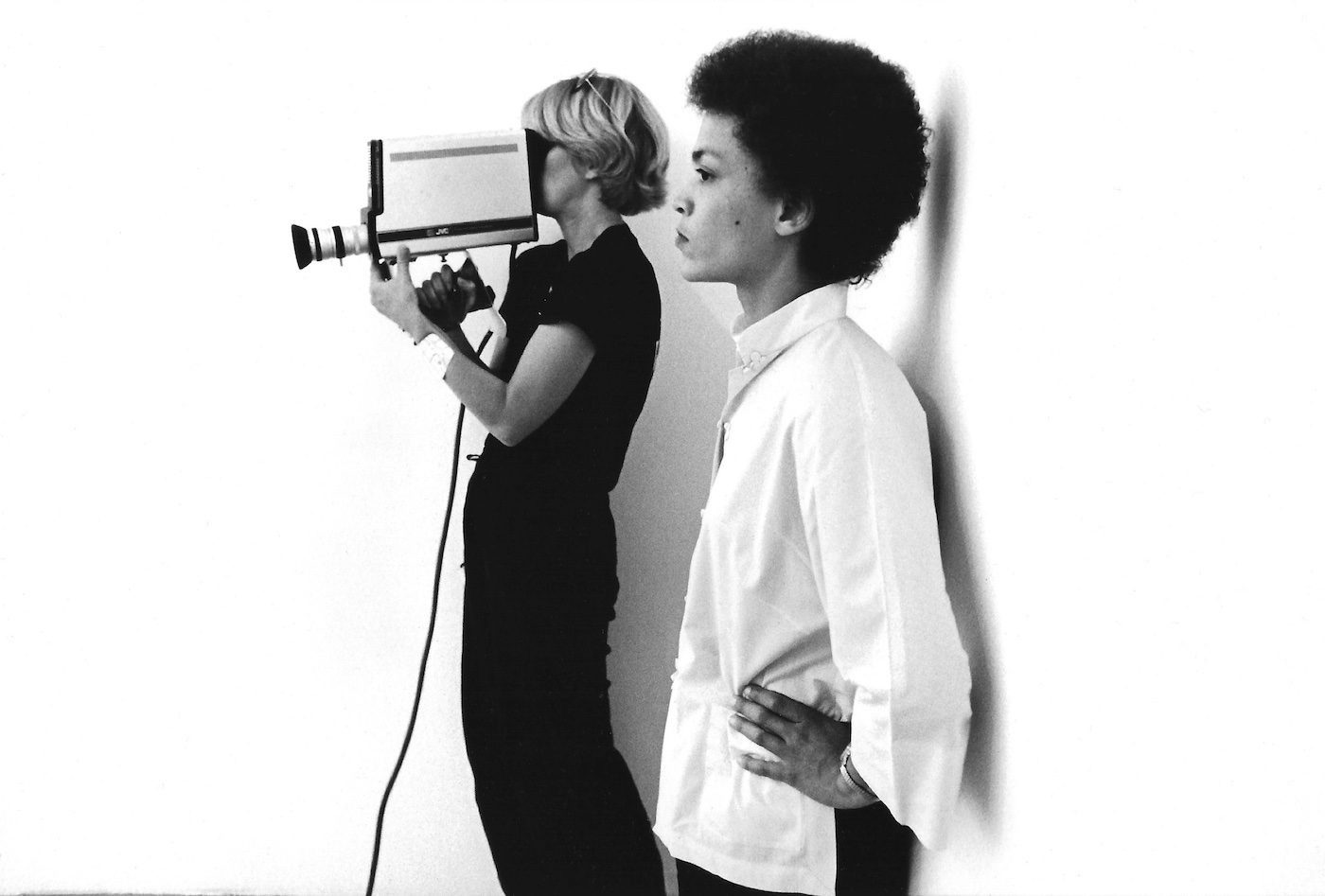

The American artist Senga Nengudi, born 1943, is renowned for her performance-based sculptures and installations exploring aspects of the human body in relation to ritual, philosophy, and spirituality. Nengudi is regarded as a core member of the African-American avant-garde – with artists such as David Hammons and Maren Hassinger – as it was concentrated in …

<p class="p1">The American artist Senga Nengudi, born 1943, is renowned for her performance-based sculptures and installations exploring aspects of the human body in relation to ritual, philosophy, and spirituality. Nengudi is regarded as a core member of the African-American avant-garde – with artists such as David Hammons and Maren Hassinger – as it was concentrated in Los Angeles during the 1970s and early ‘80s.

</p>

Naomi Beckwith: I’d like to start our conversation from your recent work, so that we’ll trace our way back. You just mounted the show Lov u – what inspired that?

Senga Nengudi: Well, I have this kind of voyeuristic way of overhearing snippets of conversations (like when I’m on the New York subway). When people talk, when you get off the phone, for instance, it always ends in: ‘love you.’ And this phrase isn’t obligatory, it comes from a real place. From there I started thinking of the people I love and examining true love. I started gathering definitions from friends about what love means to them. I worked with students, I created a photo book, I got the local community involved and had them and the students take pictures with things they love. People were pleased to have to think about love and not just in a romantic way. And that’s what I wanted: the exhibition to be a place for conversation about how love functions in your life. I also wanted to use materials like masking tape. I work with the materials and then figure out the message as I finish. Some people accuse me of being too cerebral but I was just doing things, making my art, and realized many people I feel deeply about were no longer on this plane but are symbolically represented in this work, they are always with me.

Beckwith: It’s also a very multi-media work.

Nengudi: I knew I wanted it to be multi-media work but it had to be a lo-tech multi-media. Things that were available felt right for the situation. I also wanted a soundtrack, to go along with the visual, putting you in the mood, so to speak. Some of the sounds are very abstract like Cecil Taylor, and some literal music, like Nancy Wilson and Isaac Hayes. I noticed that there’s rarely any sound in galleries but in our community there’s always sounds: In Cuba music is everywhere, in Harlem that’s true too. I could not tolerate the idea of not having sound in the show. At the last hour of the last day of the show, I changed the soundtrack to an “om” chant--it was a way of clearing the energy and purifying the space.

Beckwith: You also recently re-performed RSVP at Contemporary Art Museum Houston – how was that for you?

Nengudi: Very difficult. My pieces are fairly simple so you would think it would be easier but obviously I’m not in that same space. I do find that RSVP still has legs because some of the issues it dealt with are more intense now than when the work originated. It was about things related to feminist issues, to a sense of body, how body issues related to self-esteem and self-acceptance. It was also about entanglements--being entangled by my stuff and stretching oneself beyond your limits. Having that sense of elasticity is still very important and that I use the same materials. No one really wears pantyhose anymore but people still read them as being about restriction. I was pleased at the emotional responses at CAMH, especially from women who said that they felt like their story was being told. Those comments were very special to me.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYQWJsgIZL0

Beckwith: RSVP was visionary in that is was an ephemeral performance and it made an object—did you think of that consciously at the time?

Nengudi: You know, people talk about Richard Pryor and how his comedy was true stuff: whatever he was feeling, he gave to the audience with no buffer. In a sense, this was me laying my guts on the line. I was going through a lot of stress and wanting to express it. I was experimenting with materials like resin, glue and I didn’t know where this was going but I had to try it. I knew I had three interests: working with material, working with space, and working with emotions. And I always get back to a relationship to the body. When I was growing up in L.A., there was this place downtown called Clifton’s Cafeteria. The owner may have been religious because there would be these little nooks and cranny’s that look like Roman catacombs or grottoes on each floor of the café. I’ll never forget this: you had to go down to the basement for the bathroom and at the bottom of the stairs was a giant Jesus statue and you could sit on his lap! I related to that when I wanted to be a sculptor, I want people to touch things.

Beckwith: You don’t just want to make an object in space but an object with a relation to the viewer’s body.

Nengudi: Yes, I was in a dance class where we were told to hug yourself. I realize that we go through the world without touching ourselves or others.

Beckwith: It seems these objects aren’t really abstract; they are about a body’s relationship to another which can be very political.

Nengudi: Exactly. These objects were related to performance and also to rituals that define these relationships.

Beckwith: Such as?

Nengudi: When I worked with dance I was interested in basic movement issues such as: how is this guy going to lift me? At the same time, I was also at the Watts Towers Arts Center and the Pasadena Arts Museum which were both very experimental. There were Happenings, and [Claes] Oldenburg and [Robert] Rauschenberg came to visit. In those places, I could move how I wanted to move, do what I wanted to do visually. Then I went to Japan where I sought out Gutai. In Japan there is a ritual for everything--even for how you talk on the phone--and you can’t veer from that or it becomes something different. And I thought: how does this involve my own culture? How does this look like African culture? All these elements blended into my performance practice but I wasn’t aware of it until much later on. It wasn’t until I started thinking about Dada that I realized that even way before Dada, way before our people hit the shores of America, there was ritual, improvisation and performance but in America, it was about survival as a way of getting through the day. Our African-American history was about how the way we are in the world is already a performance, where sometimes even the way we use language has a double meaning.

Beckwith: Your most famous public performance is ‘Ceremony for Freeway Fets’ (in collaboration with David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, and Studio Z members). How did you develop it?

Nengudi: There was just this particular energy in L.A. at the time and the home gallery was Brockman run by Alonzo Davis with Suzanne Jackson as project coordinator. Many black artists there were very interested in Sun Ra. We loosely formed this collective called Studio Z where we worked together, played together. Everyone was generous to come together to do this thing. It was African and Kabuki-like at the same time. I wanted to link the two things that seemed to have nothing in common and the linkage was the importance of ritual. In Japan and in African culture, like oral history, things have to be very specific. It also had to be a total experience—it incorporated all elements like dance, music, it involved costumes. Again, there was no separation between forms, all of it worked together.

Beckwith: How did you choreograph it?

Nengudi: It was 100% improvisation. I created the costumes, though David [Hammons] made his own stuff, and I created a public artwork as the setting. The performance was the opening ceremony, the consecration of the public artwork and space. The 70s were such a difficult time for male/female relationships in the black community. So I brought these elements together and I was the spirit that united the male and female. It was a healing. I also created these masks out of pantyhose—I had never really had the masked experience before. But when I put on the mask, I totally became another entity and I began to understand these ritual forms: once you put that mask on you become an agent of something else.

Beckwith: There was a lot of general interest in Africa at this time. How did you personally conceive of Africa?

Nengudi: When I was in college there was barely any instruction on African art though I had been interested in it since high school. I took French because every time I did research, I found that the only books of any consequence were in French. But it brought tears to my eyes to read the awful way they wrote about the people. I once visited the Museum of Man in France and saw the body of Saartje Baartman. I thought: how could they do that to a human being? Put them in a case like that?

Then one day—long after that—I was in the kitchen and I heard something on the TV--there was a lot of talking. It sounded like New York and I turned toward the TV and it was African people! They had the same tone and rhythm that I’ve heard on 125th Street. Anywhere in this world, the diaspora is. You don’t even have to work at it, it manifests itself in you. When I looked at books and museums, I found “their “ view of us but I did not find the truth. I found the real deal in myself. The real deal is looking at the old traditional African dance and dance on any diasporic city street and see the new that looks like the old.

Performance art

Filipa Bossuet: Performance as Conversation, Intimacy as Power

Sarah Ama Duah: A Journey Towards Building Contemporary Monuments

Anaïs Cheleux: Connecting Caribbean Identity Through Photography and Performance

Senga Nengudi

Senga Nengudi is Recipient of the 2023 Nasher Prize

Maren Hassinger: “We are not alive to make money”