Poetics of Immanence

06 June 2017

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min read

Contemporary And: You say that your work takes an interest in “place, in the sense of a space with its own identity.” Can you elaborate? Minia Bibiany: When I started to make the kind of installations I call “immanences,” I was first interested in what makes a place specific and how a space can welcome …

Contemporary And: You say that your work takes an interest in “place, in the sense of a space with its own identity.” Can you elaborate?

Minia Bibiany: When I started to make the kind of installations I call “immanences,” I was first interested in what makes a place specific and how a space can welcome another space inside itself. The difference made between a place and a space has to do with personal experience. When a body relates to a space’s specificity, that’s when this space becomes a place. This attention is the first criterion for the poetics of a place to emerge.

I think my experience of time and space was built by transmitted memories of the plantation system, present colonization, and the natural context of the tropical Caribbean. I was born and grew up in the Lesser Antilles, in Guadeloupe, and Guadeloupe belongs to France. In Guadeloupe, there is a strong identification with France as the governing territory that lies 6,000 kilometers away, but also a different reality, a culture and un/conscious resistance strategy challenging French assimilation policies. I see this tension in the perception of territory and the construction of identity as our paradigm.

C&: How do you find the places you work with?

MB: I usually find the places based on where I live or travel, one opportunity leading to the next. Those spaces can be a squat in Paris, a beach in Kochi, a bourgeois flat/gallery in Lyon, a kind of attic room in an artistic cooperative, a closet in Mexico City, a historical and symbolic place like the old Fort Delgrès, or an institution like the Memorial ACTe in Guadeloupe.

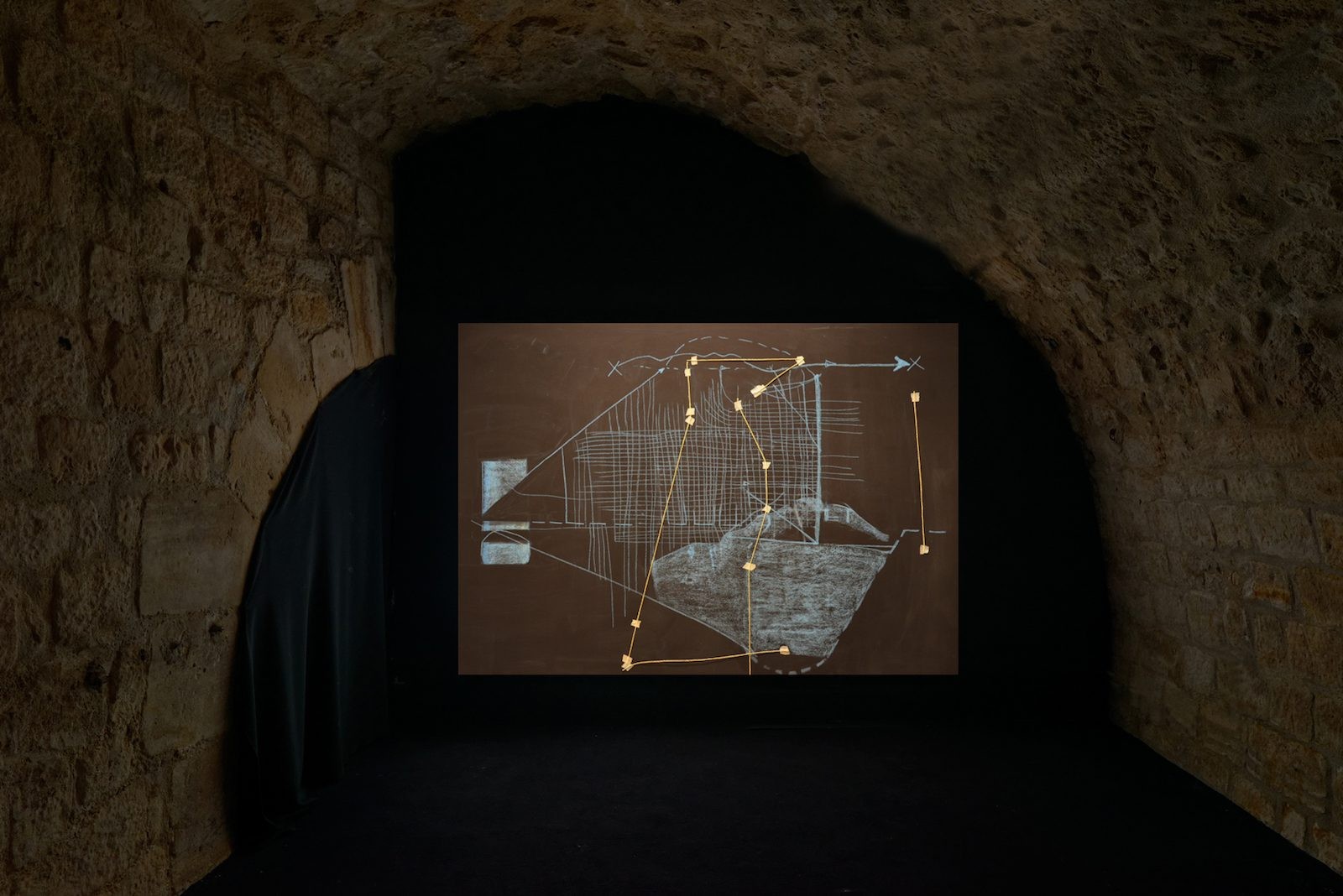

Minia Biabiany, Blue Spelling, Video Installation 2016 on view at Galerie Dohyang. Courtesy the artist.

C&: What artistic concepts and media do you use to respond to a specific location?

MB: Concepts I’m drawn to include Édouard Glissant’s “archipelagic thinking,” “relations,” and “opacity,” playing with presence/absence and notions of rupture. Archipelagic thinking creates connections and relations between elements and weaves together a space with drawings, photographs, objects, videos, or texts. “Bigidi,” the concept by the choreographer Lenablou, who perceives imbalance as another way to go forward, is important to me, as is Frantz Fanon’s “violence without cause.” I build possible routes for the spectator’s gaze using fragile or ephemeral materials, often plant matter, thread, or cotton. During the process, I walk constantly. I take a fragment, a shadow, and I repeat it. I draw it somewhere else, and I add another detail. The poetics of the place comes with the accumulation of those gestures.

C&: How does the body come into play during your artistic process and once your works are installed?

MB: In my installations, the movement of the spectator is crucial for the relations to take shape. This activates an automatic intertwining in the mind while moving and looking – like comparing shapes or recognizing a repeated word. It can seem chaotic, but connections unfold slowly without a hierarchy while reading.

C&: You moved from Guadeloupe to Mexico City to study. Why? What is the connection?

MB: I decided to come to Mexico to continue my studies after living a few years in France, where I attended ENSBA Lyon (the national fine arts school in Lyon). Once in Mexico, I got involved with Crater Invertido, an artistic cooperative engaged in autonomy strategies that challenge current capitalistic politics. I am now living between Mexico and Guadeloupe. In both contexts, my art practice and my interest in pedagogy interrogate how to undo the alienation of colonization and capitalism and what this unlearning process could be today.

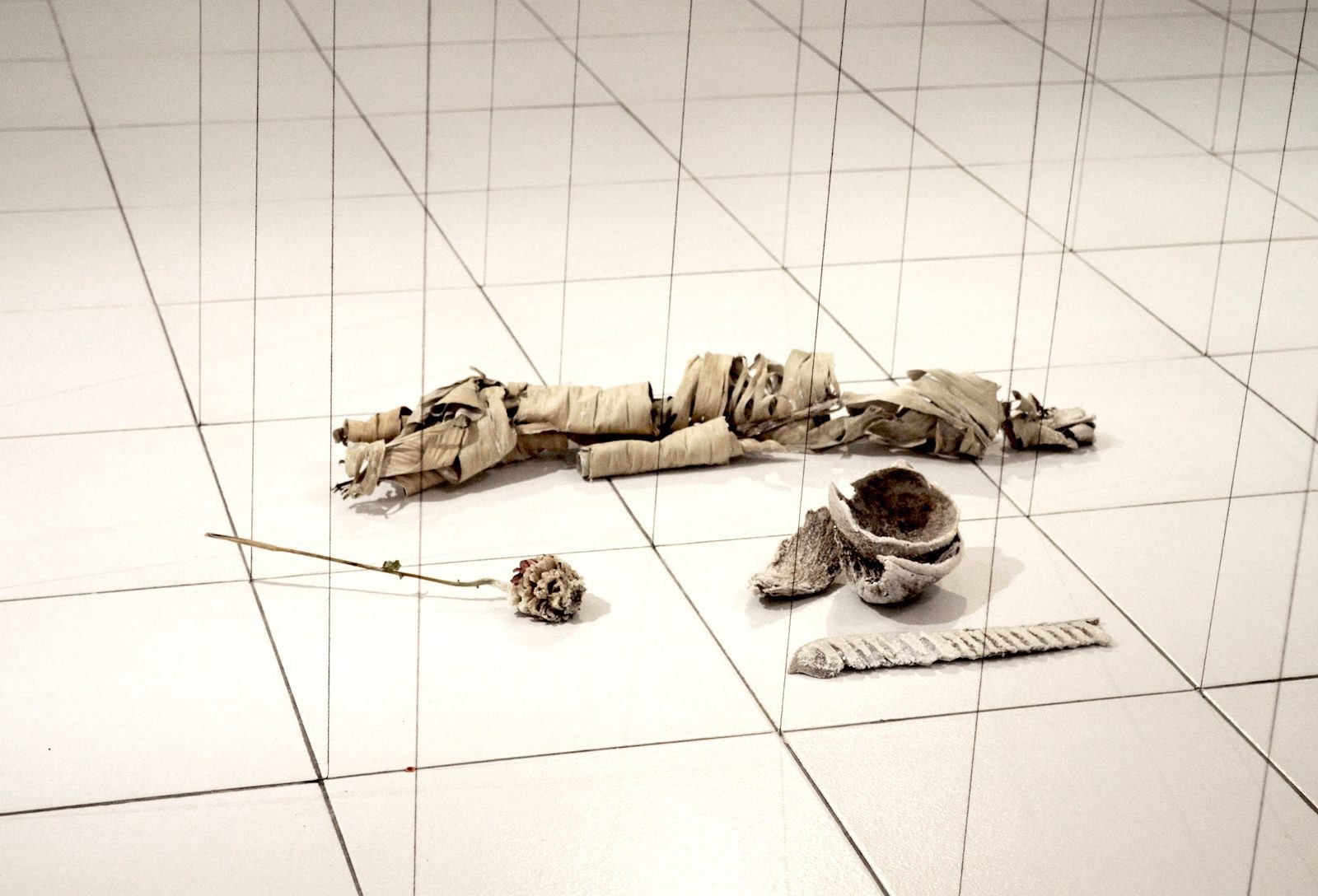

SiEntaXis (sex sintaxis) Minia Biabiany, Cráter Invertido, México DF, 2015. Installation with wood, ink transfers, plastic bag, water, photographs on transparent paper. Courtesy the artist.

C&: Together with Madeline Jimenez and Ulrik López, you conceived a series of four publications to re-print and examine selected texts by Édouard Glissant, Frantz Fanon, Antonio Benítez Rojo, and Kamau Brathwaite as educational material. What was the perception in the Mexican context?

MB: Those four publications have been conceived as pedagogical support for the Semillero Caribe, an experimental artistic seminar based on an interest in theories of Caribbean thinkers. It took place in early 2016 in Mexico City with eight public group sessions thanks to the support of Crater Invertido. We named it “semillero” (seedbed) instead of “seminario” (seminar) – a Spanish play on words – because what interested us was to create a non-traditional approach to theory by using body and drawing. As the three of us are Caribbeans living in Mexico City (Madeline is from the Dominican Republic and Ulrik from Puerto Rico), we asked ourselves how could we introduce concepts like the Glissant’s relation with the body in a place like Mexico City, where body codes generally function differently from in the Caribbean. We made a big effort at translation (all texts are in Spanish, English, and French) and divided our approaches into four general themes: the relation, body and orality, internalized colonialism, and territory. The Semillero Caribe was engaging in a political conversation about otherness, colonization, the importance of language and imaginary in the Mexican context, were those debates are often invisible despite its obvious manifestation in everyday life.

I was invited by Diego Teo to join him during his teaching in La Esmeralda art school in Mexico City after he read the publications of the Semillero Caribe. We decided to continue experimenting with body and learning processes together with his art students. We discussed opacity, silence, and idleness while questioning clichés in art studies like the idea of originality or always finding a valid discourse to justify the things you create.

C&: Finally, as a Black Caribbean woman in Mexico City, can you share some thoughts on the extremely complex and still nearly invisible issue of Afro-Mexican history and present experience?

MB: Even if Black people have been present in Mexico since long before the invasion of Abya Yala, many Mexicans ignore the existence of Afro-Mexicans even today. They are still fighting to be included in the Mexican Constitution. This issue of identity is marked by the urgency of preserving traces of Black Mexican culture and mixed with a spontaneous re-appropriation of body practices coming from YouYube dance videos, for example. The work of Casa Refugio Hankili África, rap artists like Macandal or Betún Valerio, and Beto Paredes are slowly breaking the silence about their resilience. Today, in Mexico, new Black groups are formed by the communities of migrants from Haiti who are stuck at the northern border and slowly finding their ways to establish themselves and adapt to this new place.

Read more from

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Irmandade Vilanismo: Bringing Poetry of the Periphery into the Bienal

Read more from

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones