“I like the analogy between heaven and the artist’s creative process.”

16 April 2014

Magazine C&

4 min read

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work? Zoulikha Bouabdellah: Although the Divine Comedy is an emblematic work of Western culture, it contains universal themes: questions surrounding punishment, death, and the body and its absence …

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work?

Zoulikha Bouabdellah: Although the Divine Comedy is an emblematic work of Western culture, it contains universal themes: questions surrounding punishment, death, and the body and its absence are obsessions shared around the world.

MMK/C&: In its merging of Christian beliefs and moral values as well as classical pagan topics, the “Divine Comedy” represents a deeply-rooted Eurocentric concept of society, values and culture. The exhibition aims at dismantling the European prerogative of interpretation and looking at it from a new angle. To what extent do you think this approach can lead to the Eurocentric interpretational sovereignty being generally put into question?

ZB: There is an ever-growing intellectual movement, supported by thinkers and artists from places other than the West, that is advocating a decompartmentalized approach to the world. This exhibition is part of this movement. I subscribe wholeheartedly to this vision. It is so much more interesting to connect cultures with each other and to study their positive contributions.

MMK/C&: In European-North-American art history, the “Divine Comedy” has been interpreted by numerous artists (such as Botticelli, Delacroix, Blake, Rodin, Dalí or Robert Rauschenberg) – what role did this play for you in respect to your engagement with the topic?

ZB: I am familiar with the artists you mention—and I am convinced that every artist owes it to him or herself to study them—but their influence on my work is indirect. I offer my piece, Silence, in the hope that it will add to the understanding of Dante’s work by bringing to it the point of view of a woman of dual heritage.

MMK/C&: How do religion and ethics feature in your artistic practice? And consequently, what do the terms Heaven/Hell/Purgatory mean to you personally?

ZB: Religion as such doesn’t interest me; it’s what people do with it that makes me ponder. Silence evokes the way in which women can find a place in sacred space—the prayer rug—while keeping one foot in profane space—the hole with the high heels. It is this complementary duality that recalls how heaven, hell, and purgatory are very close together and that it doesn’t take much—sometimes nothing at all—to shift you from one to the other.

MMK/C&: The over 50 art pieces in the exhibition are assigned to the areas heaven, hell and purgatory. What realm of the afterlife does your work belong in? How did this allocation come about?

ZB: Silence was chosen for inclusion in the heaven section. In Dante’s work, heaven is the culmination of a quest, the end of the soul’s voyage toward the light and eternal life. I like the analogy between heaven and the artist’s creative process, in which the latter brings warmth, gives light, instills meaning, and, as it were, delivers a piece of eternity.

MMK/C&: What is the work exhibited at the MMK about?

ZB: Silence is an installation made up of prayer rugs with circular cut-outs that reveal the floor underneath. Golden stilettos are positioned in the cut-outs. The Muslim religion requires worshippers to take off their shoes before taking their place on the rugs, thereby demarcating the sacred space of prayer. Into this space I introduced a second, profane, space, represented by a hole. It is this absence, this missing piece of cloth, that allows for a consideration of the place of the woman in these two spaces, sacred and profane.

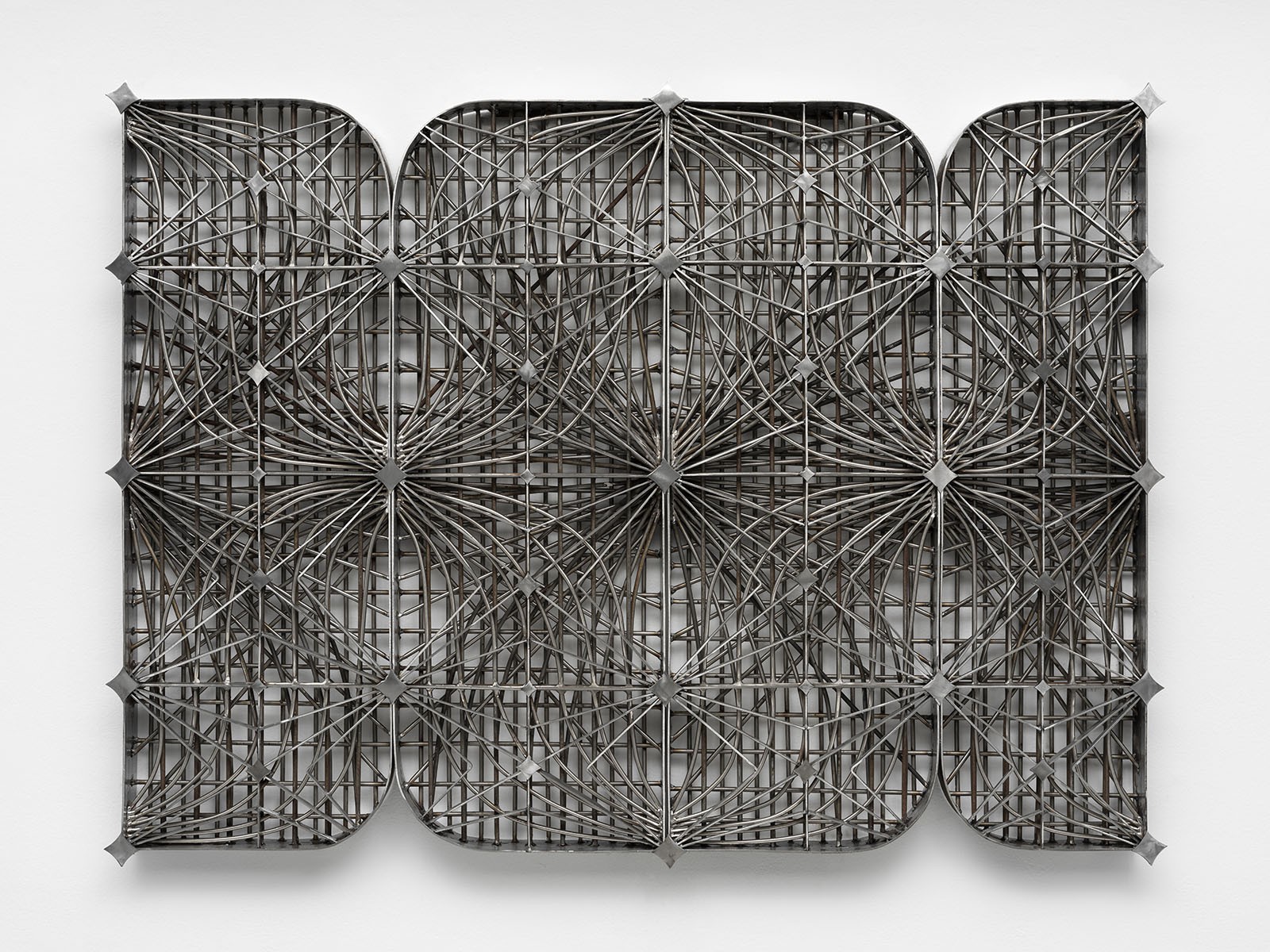

Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Silence, 2008-2014, Installation: 24 prayer rugs, 24 pair of shoes

300 x 560 cm. Courtesy: the artist © Zoulikha Bouabdellah

The exhibitionThe Divine Comedy: Heaven, Hell, Purgatory revisited by Contemporary African Artists curated bySimon Njami,MMK / Museum für Moderne Kunst, 21 March – 27 July 2014, Frankfurt/Main.

Read more from

Installation

Jesús Hilário-Reyes: Dissolving Notions of Group and Individual

(RE)COUTURE