Em’Kal Eyongakpa: “I learned mainly by exploring and experimenting with different media while guided by my intuition.”

Em’Kal Eyongakpa is the second artist to be featured in C& Art Space.

<p class="p1">Christine Eyene: You studied botany and ecology, what led you to the visual arts?

</p>

<p class="p2">Em’Kal Eyongakpa: I studied life sciences but have always been making art on the side for as long as I can remember. Studying botany wasn't really a choice. But today I feel it was probably part of some cosmic conspiracy as these dots start to connect. Since childhood I have been fascinated by what I imagined the unknown to be. I tried to transcribe what I saw in dreams/visions as well as in my observations. I loved drawing and sculpting, and wrote my own stories from a very tender age. Later my parents forbade me to spend time with crayons and to wire-sculpt my own toys. They wanted me to become a medical doctor at some point. I convinced them to allow me to study plant biology, since that field felt more like a safe haven or, say, a bridge between the arts and what they wanted. Alongside my Bachelor of Science program, I discretely recorded songs/poems, wrote personal diaries and made art to finance recordings. After a Master’s degree in plant biology/ecology, I thought a doctorate in ethnobotany would get me even closer to finding answers to my queries, or to the unknown I sought. I broke off my doctoral studies though and am only now starting to understand why: my paternal grandfather, a herbalist/shaman had just died, and the thought of my maternal grandfather, a respected herbalist/shaman as well, who died a year before my birth, kept haunting me. I had to leave this double life behind, so I “dropped out” and turned to my all-time love, the arts, in a bid to find my own answers. At that point, recording my observations in different artistic media was simply a response to the chaos I found myself in. The grandson of two shamans, whose parents happened to be Christians, kept on living, exploring, failing, growing.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: When we first met, you introduced yourself not as a visual artist but as a sound artist. Could you tell me a bit about your practice in this field?

</p>

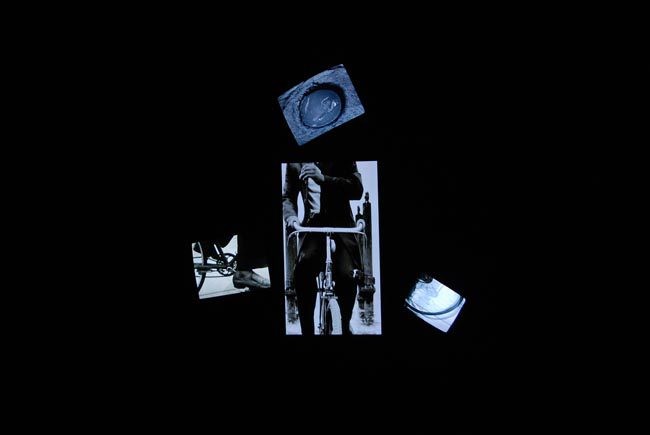

<p class="p1">EE: Strange that I introduced myself that way… probably because I am sometimes more sensitive to sound than to visual input, and that might have been one of those times. During my undergraduate studies I met and spent a lot of time with a griot and percussionist, Yakoubou Oumarou. This encounter shaped my perception, and my intuition guided me to experimenting with unconventional music produced entirely with percussive instruments and to mimicking spoken word approaches inspired by traditional music. Later on, I explored different ways of using my subjective ideas, including collage music or sound works entirely from field recordings. In this way I ended up using what my surroundings offered, and composing based on my perception and subjectivity. Some elements of these recordings are accentuated and you find quite a few repetitions, such as in rituals, which subtly relates to the recurrence of repeated lines in my photography, drawings, and wire sculptures. I currently use both techniques in composing sounds for my multimedia installations. In the recent past, I started experimenting with mapping sounds in space (exhibition spaces for example), as well as creating wire-sculpted maps (based on Google maps). The field recordings (from my sound diaries) were made in these spaces. The result seems to blur the lines between the temporality and spatiality of these media. A suggestion of how the sound is composed is achieved through animations of hand-written text and sound waves. The video animations are subsequently projected onto the sculptures to interact with shadows from the wire-maps. This accentuates both their interwoven nature and my interest in intersecting media.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: What form of training did you get in sound and visual arts?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: I didn’t have any formal training in the arts per se. I did do a two-week training session at the Roundhouse in London, as a VJ for a live music tour, “Bring the noise”. I learned mainly by exploring and experimenting with different media while guided by my intuition. I did research on the Internet every time I had trouble using different media. That was the only place I could turn, considering the nonexistence of specialized art schools in my country at the time. I basically did my own independent research on the arts. Later on, the many workshops and residencies I was granted further deepened my practice. I also expanded my knowledge in informal talks with more experienced artists and some art theoreticians and critics. My expression was more important and the various media I employ only serve as an end to express myself. I always begin with my experiences and observations, and then choose the medium that can best express a thought or chain of thoughts. With time my quest to transcribe observations and dreams led me to interactive mixed-media installations. The interwoven nature of media engages the multiple interests and sources that inform my pieces. I am also interested in the in-between, dream reality, and rituals, as well as the combination of photography, video, sculpture, and drawings.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: The late artist Goddy Leye (1965-2011) held your work in high esteem. What was the nature of your interaction? Has he, in any way, been an inspiration? If yes, how so?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: I am a great admirer of his work, but haven’t been as influenced by it as I have been by his mind and by him as a person. Goddy Leye lives on through his work and what he shared with people during his time here… To me he was a humble warrior who shared a lot with younger artists. I had several short informal discussions with him after the Panafrican Festival in Algiers in 2009 and we were supposed to spend some time together at the Art Bakery. That unfortunately never happened because of our schedules. But I definitely learnt a lot from him during our short encounters. Today I feel both lucky and unlucky to have met him for the first time while we were both exhibiting work at the Panafrican Festival. Lucky because I was already grooming something specific, something stubborn. But unlucky to not have benefited earlier from what we later on shared, or what I learnt from our informal discussions.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: Are there other artists whose work inspires you, or with whom you are engaging in an artistic dialogue?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: A lot of artists, more than I can cite here, and recently artists working on musique concrète as well as on concrete filmmaking. Also jazz and experimental musicians. I barely had access to viewing art in museums and galleries until recently. I am mostly drawn to artists who are no longer alive. But I have recently discussed collaborations with artists like Astrid S. Klein, Emeka Ogboh and Salifou Lindou among others… which I am looking forward to when time and place permits. Later this year I will do a project with the Stuttgart-based artist Astrid S. Klein, Le Dance Floor du Nouveau Monde, together with some artists from Cameroon and Stuttgart. I find the interdisciplinary nature of the project, as well as the interwoven construct, quite interesting.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: You have also produced a collection of texts. Is writing a separate activity or is it something that informs your visual practice or interacts with it?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: I keep a diary where I occasionally record my thoughts, mostly random words. On most occasions these thought energies first meet matter as words, before I attempt a visual transcription. My writing generally informs fully conceptual pieces which I tend to do less these days as I venture more into the unknown. I am looking forward to adding more threads of these words into the weave. That would allow for them to be integrated more fully, as they form an important part of my practice. In the meantime, some of these texts only exist on social media platforms on the Internet, as in"diary of KHaL!A the human" and"Njangaroon pidgin trends", a Facebook group geared at exchanging stories and poems in pidgin English/Camfranglais in many hybrid forms, in response to the increasing creolization and linguistic diversification of Cameroon in general. I continue to connect dots and experiment with how these media could intersect in an honest way.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: Less known are your “light experiments”. Was this an exploratory phase?

</p>

<p class="p2">EE: I have always looked at the camera as a tool and today I feel lucky to have been able to play with it like a kid. The fact that I didn’t have a mentor and wasn’t afraid of failing allowed me to experiment a lot. These “light experiments” are part of this exploratory phase. The experiments continue in my recent works, though in a slightly different form. This is reflected subtly in the She Moves, Naked Routes and Diary of KhaL!a experimental film projects.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: You produce a lot of preparatory sketches when planning your installations. Could you talk about your process and how you conceive your installations?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: As a child, I daydreamed a lot. Little has changed, and these sketches and writings constitute internal fights. I’m mostly caught up between experiencing these thought energies and writing/making sketches to help my dreamy nature. I don’t plan on working on something specific. It happens based on my mood and observations of a situation I find myself in. Then I realise I’m fighting and mostly resorting to giving first matter to these thought energies in words and then sketches, or vice-versa. I later on use these words/sketches in addition to memory as a base from which to plan and execute installations.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: In Njanga Wata, exhibited at the 10th Dakar Biennale in 2012 and later on at the Manchester Art Gallery exhibition We face forward, you use stop frame instead of video. What led you to choose that format?

</p>

<p class="p1"> EE: It all started with a need for expression with moving images when I didn’t have access to a video camera. I was fortunate to be able to purchase a personal photo camera after a tour in 2007. I needed to do videos so I started shooting stop frame. I later loved the result; first because I had very little choice then and second because of the ease with which it expressed the surrealistic, symbolic, paradoxical imagery I was interested in. Since then most of my work that employs moving images has been based on this technique, even after gaining access to more sophisticated cameras at the Rijksakademie van beeldende Kunsten. I stick to it except in rare situations involving performance or in some experimental films, as in the series Diary of KHaL!a.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: You have benefited from a number of residencies: Greatmore in Cape Town; Bag Factory in Johannesburg; Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. How have these residencies impacted your practice and some of your new creative steps?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: Being a self-taught artist, I have greatly benefited from these residencies. I get to talk to people who went to art school, access a library, and with the aid of the stipends and material budgets, I get the chance to experiment more. I had a productive and intense time at these residencies. Thanks to the mostly well-tailored programs supporting research, experimentation, production and presentation, my work is only getting better. At the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten for example, you have most of what you need in one place: a well-equipped library, technical workshops and advisors (art critics, theoreticians, experienced artists), work and production studios. The research I do basically strengthens my intuitive approach and technique. The technical facilities enable me to forge new ways of bringing interaction into my work, such as the use of sensors, whereas in previous projects, interactions were mainly achieved mechanically. I now take more time researching before beginning a piece, while leaving room for chances or accidents to inform the work.

</p>

<p class="p1">.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: Your work is multidisciplinary and also involves a collaborative approach, in the form of KHaL!SHRINE for instance. How did this initiative emerge, what are the objectives and who are the other artists involved?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: KHaL!LAND is a creative utopia, an ideal that has to do with one’s default state. KHaL!SHRINE, an artist-run alternative art space, is a consequence of this utopia, where the ideals of this realm can be experienced in the physical world. At KHaL!SHRINE we focus on lens-based media, sound and multidisciplinary experimentation. We have a small digital collection of lens-based and new media works from a good number of local and international artists. I started the KHaL!SHRINE project in the fall of 2007. It was born out of a basic need for a creative hub where young, practicing artists could exchange and experiment. This is one response to the absence of galleries and art centres in Yaoundé. In addition, we launched an art/wine/coffee quarterly event called “180 minutes at KHaL!SHRINE”, which has had a tremendous impact on the local art scene. This is thanks to my numerous colleagues around the world (Angela Ramirez, Brent Meistre, Erin Bosenberg, Rehema Chachage, Emeka Ogboh, Laura Nsengiyumva, Meghna Singh and others) who agreed to share their work with a community that barely sees video or new media artworks. We have a number of artists living at the space, such as budding poet and photographer Stone Karim Mohamad, Sentury Yob and Penko Simons. We have had informal art residencies and collaborations with Astrid S. Klein and Romuald Dikoume, a painter based in Douala, which ended in cross-disciplinary performances. I am currently scouting locations for a permanent, or moving, and possibly greener space in the near future. I am also educating myself more, especially along the lines of digital programming, in order to better serve my practice and these communities.

</p>

<p class="p1">.

</p>

<p class="p1">CE: What are your next projects?

</p>

<p class="p1">EE: Life! (Laughs) I am working on finalising à suivre, a video installation I started in 2012 and Diary of KHaL!A, an experimental film and a series of poems created between 2007 and 2013. This is in addition to current experiments around Interwoven: in-between, dream-reality & rituals / photography-video-sculpture, drawings and sound, a multimedia experience based on these phenomena and media, and Things we feel, an interactive project based on perception and subjectivity.

</p>

<p class="p1">Christine Eyene is an art critic and curator.

</p>

<p class="p1">

</p>

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas