How Berni Searle Contemplates the Weight of Loss

A retrospective carefully explores Berni Searle’s main subjects – ruins, residues, and loss as a uniquely legitimate site for meditating on liberation.

In the Norval Foundation’s atrium stands a dense two-part piece: a pile of paper stacked on a wooden palette, carrying the weight, or rather the lightness, of a tiny stone charred with black pigment resting on a sheet of glass. In front of this centered slab of stained white paper is a suspended fragmented picture of University of Cape Town’s Jagger Library – depicted in a wrecked state following the devastating 2021 fire that destroyed parts of the university. Right in the center of the installation appears to be a human body clad in gold cloth whose shine reflects and is subsumed by the vast gold wall it leans against. This scene and this hauntingly defamiliarized figure signals Cape Town-born artist Berni Searle’s preoccupation with ruins and residues.

<figcaption> Berni Searle, Having but little Gold, 2023. Installation view at the Atrium, Norval Foundation. Photo: Vusumzi Nkomo

In the Norval Foundation’s retrospective exhibition of Searle we encounter works from the last twenty-five years, expansive in scope and ranging from video and photography to installation and sculpture. Thematically, guest curator Liese van der Watt has combined works that explore questions of race, identity, history, gender, labor, wealth, colonialism, trauma, violence, memory, migration, loss, extraction, and dispossession. The exhibition features Searle’s more well-known works, including pieces from the Colour Me (1998–2001) series as well as Snow White (2001). Recent works in the show include prints titled Mantle I (2021), pieces from the Into the dark series (2014), and the installation Shimmer (2012–13), comprised of video projections, sculpture, and audio. The show reveals an artist grappling with concepts and mediums, continually evolving, while something recognizable about her practice remains constant at both ideational and affective registers.

<figcaption> Berni Searle, Snow White, 2001. Installation view at Norval Foundation. Photo: Vusumzi Nkomo

It is interesting to consider points of convergence and divergence between Snow White and Into the dark. The tension is easily spelled out by the respective references to “dark(ness)” and “white(ness)” in the works’ titles; to me they seem to suggest, in a Fanonian sense, a certain irreconcilability in their structures of articulation while invoking a reliance of one on the other. In the latter title, the preposition “into” indicates that darkness is a place that one goes to or enters, even though it is not too clear whether we, the audience, are called upon to go into the dark or if the dark is a place exclusively inhabited by the artist’s body, subject, and self. In the two-channel video Snow White, the capitalized “W” suggests that what is under scrutiny concerns a historically specific subject position, and its overrepresentation of itself as sovereign or Man, to borrow from Sylvia Wynter, rather than a mere color. The work is indicative of a certain kind of cold cruelty and excess enjoyment that is dependent on Black suffering. In the photographic series Into the dark the subject remains silent, passive, and supine in its deathliness; we only learn about the destruction of the body (and psyche) retrospectively as we read about the work’s subject: the Marikana Massacre of 2012. By contrast, in Snow White the violence is current and insistent and seems to descend from an unspecified and indeterminate place, as the artist’s body is covered in falling flour. In Lacanian psychoanalytic terms we might call it the locus of the big Other that, on the left screen projection, gazes at the subject from a bird-view perspective. It overwhelms and subsumes the body. Even the moments of transgression and refusal, Searle seems to suggest, are conditioned by this space of (white) violence and (white) onto-epistemological order.

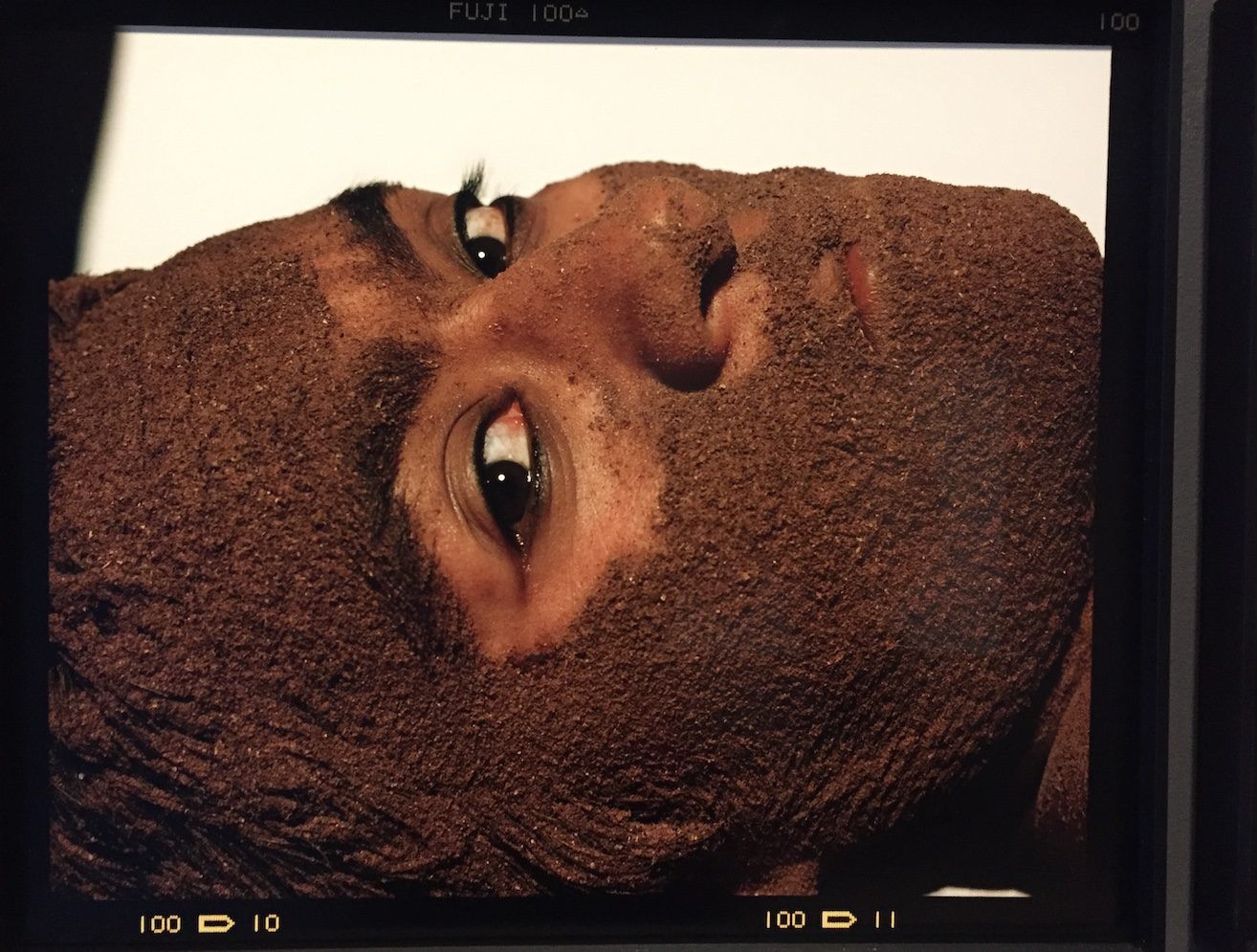

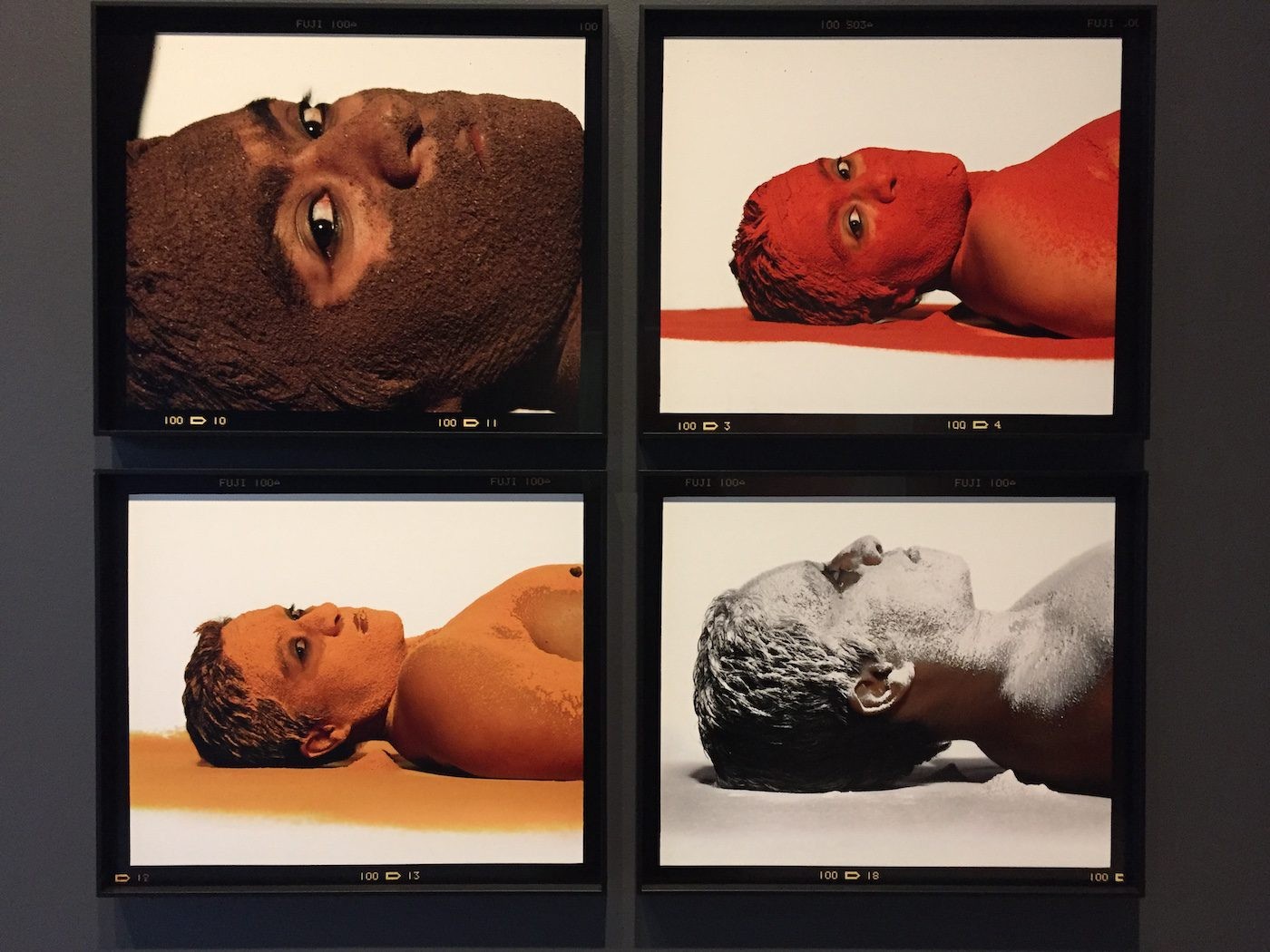

<figcaption> Berni Searle, Untitled (red, white, yellow, brown), 1998. Installation view at Norval Foundation. Photo: Vusumzi Nkomo

Throughout the show, the body, or more precisely, the artist’s body, is marked by highly pronounced meanings and is constituted as what Desiree Lewis, professor of women and gender studies, called, in a text on Searle for Agendajournal in 2001, “objects of the gaze.” Or, quoting film theorist Laura Mulvey, Searle’s approach could be read as a “to-be-looked-at-ness.” In Untitled (red, white, yellow, brown) (1998), from the Colour Me series, a still and supine Searle stares dead silent at the perceiving subject; this muteness reverberates throughout the retrospective, reminding me of Lewis’s caution that Searle’s figures are caught in a web of violent meanings that are “extremely difficult to dislodge,” that signals a “legacy of scrutiny.” Searle’s looking weighs on you; it may be what philosopher Lewis Gordon calls a “form of illicit seeing” that reaches at you, beckoning you to bear witness. However, both Lewis and the late artist Mgcineni “Pro” Sobopha have argued for some transformative potential in Searle’s work, Sobopha asserting in Agenda in 2005 that Searle “demystifies and fractures our understanding not only of colour, but she also creates new meanings.”

<figcaption> Berni Searle, Mantle I, 2021. Installation view at Norval Foundation. Photo: Vusumzi Nkomo

The muteness in the show is most productive in a dual-screen video installation fittingly titled Mute (2008), where the subject, Searle, is not still or apathetic but bereft of speech and sound. Her face is flooded by tears as she struggles to control her emotions, triggered by whatever she is looking at, which to us appears to be a screen of still photographs on the opposite panel of the wooden booth where the work is mounted. We learn from the vinyl wall text that Searle is responding to the 2008 xenophobic (or more accurately, Afrophobic) attacks by South Africans against foreign nationals, primarily of African descent. Mute reveals a chasm in language; an unbridgable gap that marks the space between the articulable and the inarticulable. Searle, her body and gestures engulfed in smoke and interspersed by floating and burning black crosses, stares at moving images that move her to break down and cry. Failed by words, it seems that whatever terror she is looking at (because she can’t look away) can only be approached by way of tears. However, the title, Mute, is suspicious to me: it could easily slip into being problematic and ableist in its suggestion that those who can’t speak, either because they lack the faculty of speech or can speak but do not have the words, are both “mute”; this seems to collapse the distance, which constitutes a difference, between these two subjects.

Lastly, Searle continues to be concerned with a historically particular problem: that of a structural loss that she maps and traces from Cape Town to Marikana, Congo to Belgium, in Mauritius, Saudi Arabia, in the Strait of Gibraltar between Spain and Morocco, or in the former Gold Coast of Africa. For Searle, the space of psychic, personal, and political loss is, in our troubled times, the only legitimate site upon which any meditations on liberation might take place.

Having but little Gold: Berni Searle runs at the Norval Foundation in Cape Town from 15 February 2023 to 13 November 2023. Vusumzi Nkomo is a writer based in Cape Town.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission