How art deals with the carving of a continent

30 November 2014

Magazine C&

6 min read

Berlin has managed to reconstruct itself, break down its borders, and build up a reputation as a dynamic, vibrant international cultural capital. This is reflected in the multiplicity of artistic perspectives represented in the exhibition Wir sind alle Berliner: 1884-2014, a reflection and response to the historic Berlin conference. The 12 participating artists are Kader …

Berlin has managed to reconstruct itself, break down its borders, and build up a reputation as a dynamic, vibrant international cultural capital. This is reflected in the multiplicity of artistic perspectives represented in the exhibitionWir sind alle Berliner: 1884-2014, a reflection and response to the historicBerlin conference. The 12 participating artists are Kader Attia,Theo Eshetu, Satch Hoyt, Cyrill Lachauer, Henrike Naumann, Katarina Zdjelar, Bili Bidjocka, Thabiso Sekgala, Sammy Baloji, Filipa César, Mansour Ciss, and Nadia Kaabi-Linke, the majority of whom have established their creative home in the German capital.

Here, Berlin's status as a cultural, political, and historical center also raises many questions of collective memory. The inscription of Germany's colonial past in the collective imagination and its strategic role as epicenter during the Berlin Conference remain mostly unexplored. How fitting, then, to take possession of these walls as a space of transformation and to delineate positions adopted in contemporary art practice as a way to invite reflection on the epistemological space of memory. Such are the stakes of this exhibition: to “propose a space for deliberation” retracing the consequences of this conference, both in the historical expression of a nationalist and racist Europe and in the current socio-political situation regarding Europe's immigration controls, the strengthening of its geographic and cultural borders, and the increasingly disturbing populist parties encouraging ever more complex forms of exclusion. The exhibition's introductory statement reinforces this element in no uncertain terms: “What hasn't been said explicitly about this conference is that, while it altered the contours of the African continent, it also changed Europe!”It is therefore a shared history that must now be inscribed in memory through a collective reflection sustained by mutual dialogue. By reminding us that history is written in the present, Berlin's independent art scene has boldly set out to acknowledge this history and speak out.

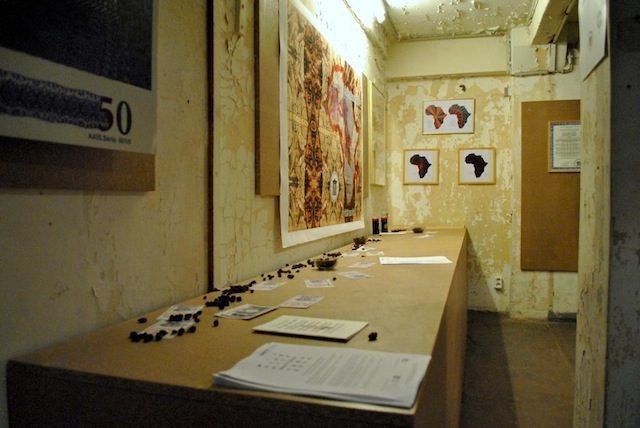

Laboratoire de Déberlinisation, installation by Mansour Ciss © Photo Chiara Cartuccia, 2014

.

One enters the exhibition intrigued by this atmosphere of engagement. There is no explicit trajectory for interpreting the questions posed by the ensemble of works, for the Savvy laboratory's physical layout is circular, negating all possible hierarchical strategies for installing and hanging art. The signature of the curator is also suppressed to make room for the collective idea embodied by the project. On the night of the opening, curatorSimon Njami withdrew to the booth installed by Laboratoire de Déberlinisation (laboratory of deberlinization) to sell the imaginary pan-African currency, the “Afro,” becoming both a participant and worker in the installation by Mansour Ciss, whose project encourages us to reflect on the right to political and financial self-determination by way of interrogating the (speculative) value of art. Responding to the Berlin Conference, the Laboratoire denounces a colonial expansion whose damaging effects are at the origin of the contemporary political and economic crises on the African continent. Engaged in this postcolonial perspective, the viewer enters an isolated room whose precarious interior houses a large-format video projection by Kader Attia entitled "Oil and Sugar #2", depicting a close-up of a sugar cube structure being dissolved by a blackish liquid, presumably oil. As the title indicates, the video portrays the sluggish progress of a chemical process contrasting solid and liquid matter, emphasized by the saturation of black and white. Beyond the formal characteristics of the piece and the sensations it generates, the conceptual framework proposed by the exhibition statement stresses the metaphorical value of the artist's approach. By assembling minimal shapes and playing with the typical representation of cultural objects, the artist questions the relationships between art, economics, and power. Thus sugar cubes may bring to mind the cubic form of the Kaaba, the holiest site of Islamic worship, and the oil may be taken to symbolize Western societies' economic interest in North African and Middle Eastern countries. Finally, the sugar might evoke the ravages of the colonials' exploitation of sugar cane fields. By entering the next room, the home of Savvy's documentation center, one can supplement the visual experience by exploring, for example, the documentation presented by a side project of the exhibition:Colonial Neighbours, a public archive of everyday objects bearing the narrative traces of the history of colonialism that connect Germany's colonial past to the contemporary cultural landscape.

Mémoire, photomontage series by Sammy Baloji © Photo Chiara Cartuccia, 2014.

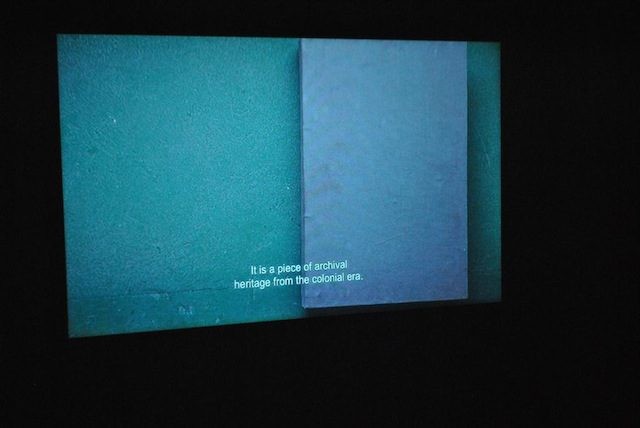

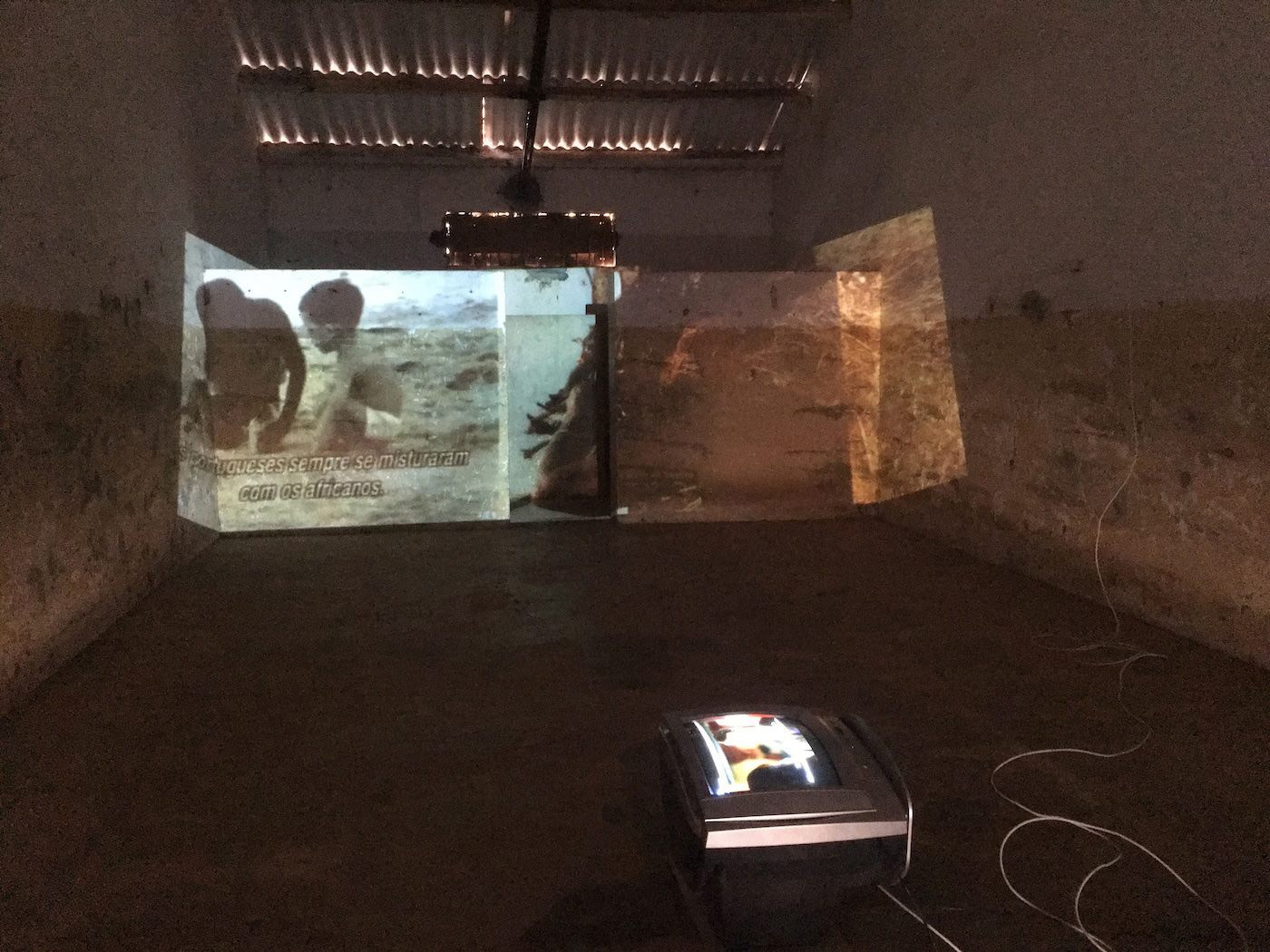

One continues to reflect on the close links between the cultural, industrial, and colonial legacy with Sammy Baloji's series Mémoire, which also bears the imprint of memory at the heart of this exhibition. The series of photomontages is composed of appropriated black-and-white archival images of subjugated colonial populations superimposed upon color photographs the artist took of devastated industrial landscapes in his native region of Katanga, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Manipulating historical stories and archival imagery in order to question the modes of production of memory is also what Filipa César does in her video The Embassy. The creative gesture dissolves through a static overhead sequence shot in the point of view of the narrator, archivist Armando Lona, as he comments on an album of photos taken by Portuguese colonists in Guinea-Bissau between 1940 and 1950. Through her cinematic gaze, Filipa César becomes an intermediary between two contemporary realities, interrogating the effects of history's inscription on both the viewer in Berlin and the Bissau-Guinean archivist.

The Embassy, video projection by Filippa César © Photo Chiara Cartuccia, 2014.

These twelve artists’ contributions are all engaged in reactivating historical memory by re-appropriating story, imagery, and coded cultural representations, inviting us to reflect on contemporary society. If Berlin is a laboratory for the continual exchange and flux of ideas, we must remain focused on ensuring visibility for the various cultural expressions mobilized here. Neither this article nor any piece of art criticism are sufficient means to support artistic creation that attempts to subvert the amnesia of Eurocentric politics. This work compels us to recognize the necessity to (re)think, renew, and mobilize. And that is precisely what the exhibit intends: to showcase the mark African perspectives have made on art, forming an integral part of the social fabric in Berlin and Germany at large – and that is nothing new!

The Embassy, view on video projection by Filippa César © Photo Chiara Cartuccia, 2014

Wir sind alle Berliner: 1884-2014, SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin - November 15, 2014 - January 11, 2015

Elsa Guily studies art history and is an independent critic living in Berlin. Specializing in the relationship between art and policy, she is currently writing her thesis on the concept of how history is rewritten in contemporary art through the reappropriation of archives.

Read more from

Post-colonial

Cabo Verde’s Layered Temporalities Emerge in the Work of César Schofield Cardoso

What’s Behind Decolonial Movements in Brazil?

Osei Bonsu: A Curatorial Lens on Photography as Identity and Tradition, Counter-Histories and Imagined Futures

Read more from

Kader Attia

Marie Hélène Pereira: “I’m very fond of conversations that take you out of the over-intellectualization of things”

12th Berlin Biennale Announces Artistic Team