Our author Dagara Dakin takes a closer look at the retrospective of Hervé Télémaque's artistic body of work.

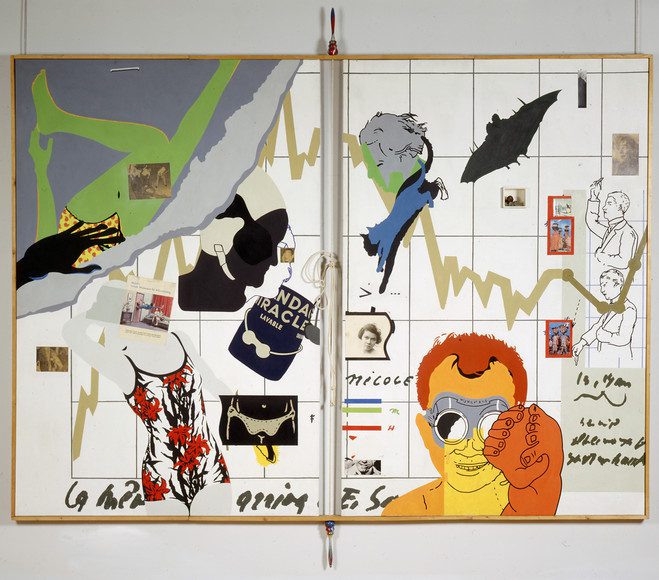

Hervé Télémaque, Convergence, 1966, Acrylic, collage and objects on canvas; skipping rope — 198 × 273 cm Saint-Etienne, Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de Saint-Etienne © Adagp, Paris 2014

Following on directly from the exhibition Haïti, deux siècles de création artistique [Haiti, two centuries of artistic creation], recently shown at the Grand Palais in Paris, the Centre Georges Pompidou presented a retrospective until May 18 of the work of Hervé Télémaque, a French painter of Haitian origin. The exhibition will run at the Musée Cantini de Marseille from June 19 to September 20, 2015. It provides the opportunity for a clear definition of Télémaque’s oeuvre with its characteristic urgency and technical diversity. To quote Christian Briend, who was responsible for commissioning the project: “It clarifies fundamental considerations for the artist, such as the role given to autobiography, the complex relationship between image and language, and the narrative dimension.”

Route

Hervé Télémaque was born in Haiti in 1937. His artistic development occurred mainly at the end of the 1950s in New York in an art scene dominated by abstract expressionism. In 1961 he moved to Paris at a time when that luminous city was losing its aura as the capital of the arts to New York. “Paris attracted me in 1961,” he says, “whereas New York, a city imbued with racism, disappointed me. Confronted with the lack of a critical view of society by American painters from the pop art generation, aside from James Rosenquist, I decided to leave New York and move permanently to Paris.” The artist’s need to relate to the French language he was educated in was an additional motivation for his departure from the United States.

In France he met the main actors of surrealism without actually being attached to the movement. His visual language evolved under the influence of advertising images – which he didn’t hesitate to divert for his own purposes, as in the work Petit célibataire un peu nègre, et assez joyeux (1965) [Little bachelor slightly negro, and quite happy] that was used as the poster for the exhibition. Comics were another major influence, notably those by Hergé; Télemaque appreciated his technique of clear lines. In 1964, in collaboration with the painter Rancillac and the critic Gérald Gassiot-Talabot, he organized the exhibition “Mythologies quotidiennes” [Everyday Mythologies] at the Musée d’Art Moderne of the city of Paris. This event marked the birth of the narrative figuration movement, which was presented as an alternative to abstraction and, at the same time, as a critical perspective on consumer society.

Télémaque’s work uses a great variety of techniques and is notable for its hybrid character. Inspired by American artist Robert Rauschenberg’s combines, the artist inserted objects into his own works (Présent où es-tu ? – [Present, where are you?]), and liberated himself from the classical format (My Darling Clémentine, 1963), and from the exhibition wall (Conquérir, (1966) [To Conquer]). In addition, when he was dissatisfied with painting in 1968 he devoted time to creating objects, and returned to them in 1970, making collages between 1974 and 1980, and assemblages from 1979 to 1996. Parallel to this, he experimented with charcoal drawing (1993-2002).

His more recent paintings (2000-2015) deal with explicitly political subjects that refer to his African roots and current French politics (see Fond d’actualité, n°1 (2002) –[News background No. 1]).

Hervé Télémaque, Le Voyage d’Hector Hyppolite en Afrique, 2000, acrylic on canvas, 162 x 243 cm.

© Paris, musée d’Art moderne / Roger-Viollet © Adagp, 2014

The art of the ellipse

Hervé Télémaque’s works do not reveal their content easily. And, although the artist denies it, there are some similarities with the principle of the “rebus,” a puzzle composed of parts of words or pictures. It is this idea that springs to mind when we look at his art works. For example, the canvases that make up the series Passages (dating back to the 1970s) are dotted with a number of solid figures such as the white cane, the whistle, the scissors, umbrella or the hunting horn. The presence of these diverse and incongruous elements in the same graphic environment may seem strange to the average person’s eye, but from the artist’s perspective: “People have lost their ability to see the latent sense hidden in everyday objects. The strange thing is not that I myself have recovered this sense, but that other people have lost it.” Given the depth of the artist’s reflections, the term “rebus” is undoubtedly reductive. But the works certainly leave a puzzle for the viewer.

It is hardly surprising that, as Jean-Paul Ameline has pointed out, “certain art critics have frequently seen Télémaque’s pictures as an occasion for difficult exercises in interpretation. Others have spoken of the ‘labyrinth’ where the mystery is haughty, hermetic and ironic.”

Referring to the role of language in his work, Télémaque has said, “Being elliptical gives us the chance to enjoy things after the event where we encounter a kind of lived experience again. I go through an analytical process, nourished by dream images and starting from the word or the language, a permanent process of coming and going between the dream and the spoken word, for that is an analysis.”

An autobiographical dimension underlies some of his works (including Présent ou es-tu ? (1965) [Present, where are you?], L’annonce faite à Marie (1959) [The Annunciation to Mary] or Confidence (1965)). This dimension is not counterposed to the hermetic character the work may assume. The composition Confidence – that had to be restored for the exhibition – illustrates this perfectly. It associates several biographical elements such as the orthopedic bandage, a reminder of a hernia the artist suffered at the age of 13, as shown in the composition. The artist explained; “I stenciled the words ‘being a trapeze artist’ and the verb ‘being’ is crossed out. In fact, that accident forced me to give up high jumping, and I had been one of the minor hopes for a medal in Haiti.”

The role of dreams and analysis in his approach to painting has echoes of the approach of surrealist artists. Beyond that, his “sexual vocabulary,” as he himself refers to it, is “indirectly inspired by Marcel Duchamp: sheaths, bra, panties, slips… there is a bit of Duchamp and of La Mariée mise à nue par ses célibataires, même [The Bride stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even] in Confidence, but maybe it is really in my work Caca-Soleil! This involves many more connections.” We can also see this influence in the construction of some specific titles of his such as Petit célibataire un peu nègre, et assez joyeux.

The critical dimension

Télémaque has always regarded the critical dimension of his work as very important. This is evidenced by some of his exhibits and by the fact that the absence of a critical approach among American pop artists was one of his arguments for leaving New York. In addition, beside subjects of an autobiographical nature, he has tackled themes such as racism, colonialism and imperialism.

The works dealing with these issues include La Vénus Hottentote n°2 (1962) [Hottentot Venus No. 2], which relates to the question of colonial racism. The title uses the nickname given to Saartjie Baartman, a personality whose case is famous in the history of the human zoo. On a different note, racial segregation in the southern United States is the subject of Étude pour Deep South, a charcoal on paper drawing dated 2001. It was inspired by a photograph by Elliott Erwitt showing a new fountain reserved for white people and a washbasin for use by Blacks. The artist removed the figure of the Black man from the original image to eliminate any anecdotal aspects.

The triptych Mère-Afrique (1982) [Mother Africa] – a work of mixed technique that combines photography, collage and graphite pencil – reveals Télémaque denouncing the policy of apartheid prevalent at that time in South Africa. It shows a real whip from each side – a sort of ready-made – a photography of a Black nanny walking with a white child along a beach reserved for Afrikaners, and black characters, hilarious images taken from Paul Colin’s famous poster for “La Revue nègre” [The Black Vaudeville]. Violence, irony? What are we laughing at? Who are we laughing at? An absurd situation… Everything is there is this picture.

“Even today,” says Hervé Télémaque, “I’m still an ‘angry’ Black man (…). I have expressed my rebellion against American imperialism time and again. My most significant work of committed art is undoubtedly One of 36000 marines (1965), in which I denounced the United States’ invasion of the Dominican Republic one day in April 1965. Fidel Castro is the incarnation of the Cuban resistance; he plays a very important role in my work of that period. But my greatest feeling of solidarity is for Nelson Mandela.” Referring to his relationship with his origins, the artist affirmed, “I stay close to my origins while always maintaining a critical distance.”

The exhibition ends with a citation from Aimé Césaire’s book, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal [Notebook of a Return to the Native Land] that expresses the artist’s position on these questions.

“My Négritude is not a leukoma of dead liquid over the earth’s dead eye

My Négritude is neither tower nor cathedral

It takes root in the red flesh of the soil

It takes root in the ardent flesh of the sky

It breaks through opaque prostration with its upright patience.”

Hervé Télémaque’s work embodies a latent force that functions in reverse. Even after we have left the exhibition we are surprised to catch ourselves still trying to decipher the meaning of his compositions. The hermeticism he is accused of is indeed real, and his ideas are not easy to grasp. There are certainly many reasons for this difficulty in accessibility. It could be the expression of a strategy that wants to say things without having the breathing space in a context that doesn’t support free expression of certain truths. To paraphrase Patrick Chamoiseau, who spoke in terms of writing, in a certain sense it is like painting in a country under domination. Beyond this hermetic approach, or this sophistication – a term the artist prefers – is also the mark of a spirit whose erudition we don’t have point out: it oozes from his compositions. This is a long way from entertainment. Télémaque may refer to the world of the comic or to advertising, but his references are not meant as any kind of diversion.

Hervé Télémaque, June 19 – September 20, 2015, le Musée Cantini de Marseille, France.

Based in Paris, Dagara Dakin graduated in art history and is a freelance author, critic and exhibition curator.

More Editorial