Evoking Imaginary Spaces

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work? Nicène Kossentini: When Simon Njami invited me to create an artwork on the theme of Dante’s Divine Comedy and more specifically on the theme of purgatory, the …

MMK/C&: The exhibition’s point of departure is Dante‘s “Divine Comedy”. In the run-up to the exhibition, how relevant was it for you to actually engage with Dante’s work?

Nicène Kossentini: When Simon Njami invited me to create an artwork on the theme of Dante's Divine Comedy and more specifically on the theme of purgatory, the first thing I did, was to reread Dante’s work. At this stage, the objective was to delve deep into this work, but without attachment. In other words, I didn’t try to interpret the Divine Comedy of Dante and now I cannot confirm if Dante’s work was the starting point of my creative process or if its influence emerged halfway towards completing the project. Because, when I started working on the project during an artist-in-residence programme in Algiers in 2012, this idea was not originally conceived for the exhibition of the Divine Comedy, and for me, the concept of the project was not directly connected to the exhibition. But when I re-listened to the first story that I got from Algiers, I said (to myself), "here is the sense of purgatory", and I subsequently decided to develop this project and recommend it for the exhibition. I believe that my commitment to the work of Dante consists in trying to create a dialogue and an encounter between this medieval work and my contemporary work, which is created in a very different spatio-temporal context.

MMK/C&: In its merging of Christian beliefs and moral values as well as classical pagan topics, the “Divine Comedy” represents a deeply-rooted Eurocentric concept of society, values and culture. The exhibition aims at dismantling the European prerogative of interpretation and looking at it from a new angle. To what extent do you think this approach can lead to the Eurocentric interpretational sovereignty being generally put into question?

NK: Expanding our horizons and broadening our outlook serve to put one-sided views into question and to subsequently improve our understanding of each other’s culture. I'm a Tunisian citizen with an essentially Arab-Muslim culture, and it is from this perspective – which is a different angle – that I perceive the Divine Comedy. And I should here say that the perception of the Divine Comedy from this different angle could possibly create a new horizon. Actually, the fact that there are multiple and diversified views, sets the stage for multiple and different perspectives and interpretations. A unique one-sided point of view would therefore be a delusion. Building on the theology of the Middle Ages, the Divine Comedy narrates a journey through the three realms of the afterlife that lead up to the vision of the Trinity. Its imaginary and allegorical representation of the Christian underworld is the pinnacle of the medieval view of the world as developed by the Roman Catholic Church. Dante’s fictitious journey exists in Islamic popular literature, and this is one of the themes in which the imaginary Islamic and Christian traditions converge. The journey is illustrated in "The Book of the Night Journey" (Kitab al isra) written in 1198 by Ibn Arabi, the Andalusian mystic and philosopher. It is also portrayed in "The Epistle of Forgiveness" (Risalat al Ghofran) by Al Maarri, the famous Syrian writer (d. 1057). The journey to the underworld or the Night Journey, called "isra" in Islamic tradition, is intended to show the Prophet some divine signs. The ascension to the heavens “Miraj” started from Jerusalem, with the Prophet being accompanied and guided by the Archangel Gabriel. In fantasy and popular Islamic culture, the Prophet travelled on the back of a winged bridled steed named "Buraq" which was a woman-faced, peacock-tailed beast, smaller than a mule and bigger than a donkey.

MMK/C&: In European-North-American art history, the “Divine Comedy” has been interpreted by numerous artists (such as Botticelli, Delacroix, Blake, Rodin, Dalí or Robert Rauschenberg) – what role did this play for you in respect to your engagement with the topic?

NK: Honestly, these different artistic interpretations that I personally admire didn’t play any role in my approach or commitment to this theme.

MMK/C&: How do religion and ethics feature in your artistic practice? And consequently, what do the terms heaven/hell/purgatory mean to you personally?

NK: I think that the concept of religion is not directly conveyed in my artistic practice, although one can notice the influence of mystical thinking in my work. I think religion, as a constituent element of the culture of each person, necessarily influences our perception of the world. It is important to note, however, that the concept or idea of purgatory does not exist in Islam. Thus, unlike Christianity in which the belief in Messiah/ Redeemer brings salvation and eternal bliss and in which purgatory serves as an intermediary state for those destined for heaven, in Islam all actions taken by a person during his/her earthly life shall determine his/her ultimate destiny, whether it is heaven or hell. Personally, I have a fuzzy idea of the two concepts of heaven and hell in my head, despite the various detailed descriptions of these two places of the afterlife in the Quran. I believe in the existence of another life, but I’d rather address life down here, where I can confirm my existence and try to grasp its meaning.

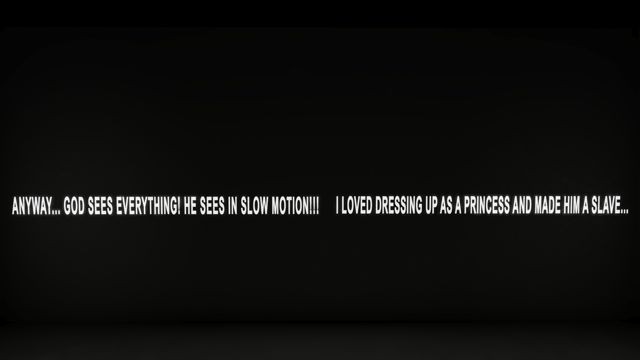

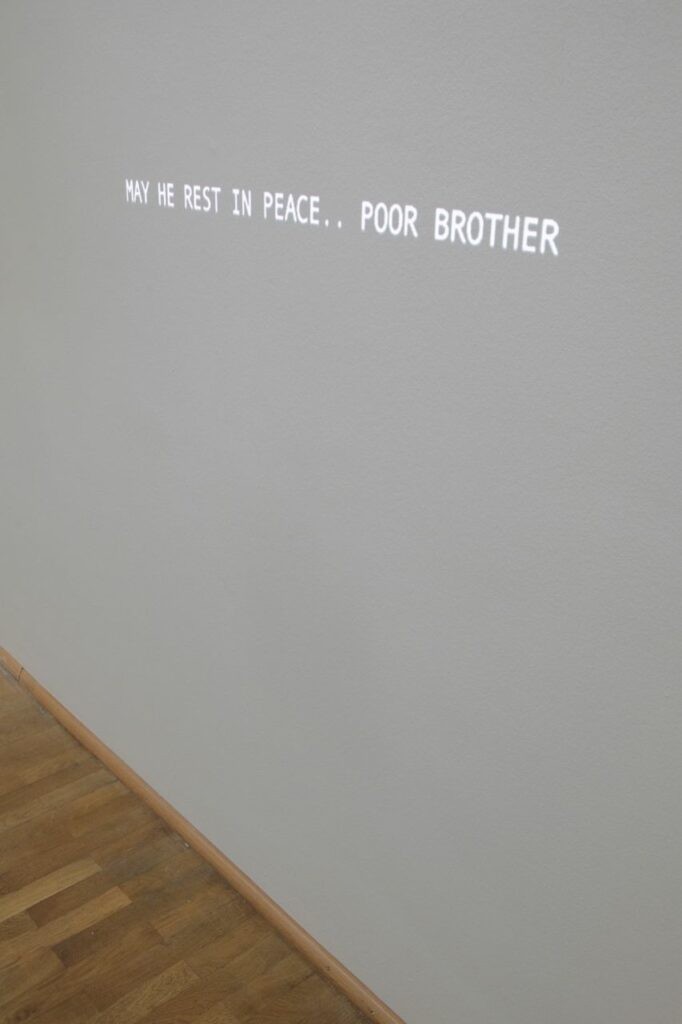

<figcaption> Nicène Kossentini, Spawn and wrack (Frai et varech), 2013, Installation view MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, Courtesy of the artist and the Selma Feriani Gallery, London

MMK/C&: What is the work exhibited at the MMK about?

The work that I present at MMK is an installation of six video projections. The six videos are exempted from figurative representation. The words, whether oral or written, are the unique elements of the videos. They replace the absent images to evoke imaginary spaces. The project is about six stories told by six Algerians. Each person looks back at his or her life and spontaneously relates his or her most important memories. The six stories are told in Algerian dialect which is a mixture of Arabic and French words. They are screened simultaneously, accompanied by a transcript translated into English. The subtitles appear in single lines and proceed following the rhythm of the narrative.

MMK/C&: (If it was commissioned:) How did you go about the creative process?

NK: I was invited to participate in the project for the exhibition of the Divine Comedy five years ago. Having such a relatively long period of time gave my work the chance to evolve and go into the desired direction. Actually, the creative process of this project required a long time. And, as I said earlier, the project was conceived during an artist-in-residence programme in Algiers. At first, the project was a personal journey. I set off in search of my own history of long ago but also the present. A few centuries ago, my great-grandparents left Constantine, Algeria and settled in Tunisia. Today, there is no tangible trace that binds me to this origin, which is uniquely indicated by my surname: Kossentini (i.e. originating from Constantine). I wasn’t interested in the country's history as recounted in books, so I went to track the origins of the country’s past through the different stories lived by ordinary people in Algeria. The quest was not easy because Algerians are very reserved and introverted. During the first twenty days of my residence, no one wanted to talk and to record his or her own story. The first woman who agreed to tell me her story was "Keltoum". I met her by chance at a Berber jeweller in the street in the centre of Algiers where I was staying. She was having an argument with the jeweller about the war in Algeria, and as she turned to ask me my opinion on the subject, I told her that I did not know the story and that I was there to find out about it. As I briefly introduced the project to her, she agreed to recount her life story. I met most of the people who agreed to tell their stories by chance and in different circumstances, often in public places in Algiers. These ordinary and anonymous people whom I had met by chance agreed to recount their stories during very brief meetings of a few hours, the time required to make the recordings and for them to tell their stories spontaneously, without any instructions on my part. As simple as they are profound, those stories are tiny fragments of the true history in which the true meaning of things is hidden.

The exhibition The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Hell, Purgatory revisited by Contemporary African Artists curated bySimon Njami,MMK / Museum für Moderne Kunst, 21 March - 27 July 2014, Frankfurt/Main.

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas