Emmanuel Iduma’s Archive Attempts to Hold All That Is Intimate

02 August 2023

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Joseph Omoh Ndukwu

7 min read

The artist has created a participatory digital archive around the tenderness in photographs, refusing temporal linearity by drawing out a kinship.

After describing The Bondo Culture, a photograph of a woman with closed eyes bearing on her head a bowl wrapped in a shawl, Emmanuel Iduma asks: “What is this balance, this serenity, this inner vision?” The photo, by Hickmatu Leigh, is featured in Iduma’sTender Photo, a Substack of photographs by African photographers currently working on the continent.

Iduma’s question reveals something of the essence of his Substack. In his curation lies a striving for balance between what a photograph is and what it is expected to be – a yearning for serenity and tenderness, a vision that disrupts merely aesthetic or critical concerns.

<figcaption> Hickmatu Leigh, The Bondo Culture. Courtesy the artist.

Iduma began Tender Photo in February 2022 as an archive of the work of early to mid-career photographers. So far, over sixty-five photographs from around Africa have been published on the platform, many of which are made by young people. They are photos of our time (almost none are older than five years). The fact that they are so near to us in history and subject make this a rather unusual archive. It is built from the material of the present and grows with the ebb of the living moment.

Each entry generally follows this structure: the photo is presented at the top with its title as the header. Then comes a short paragraph by Iduma, describing and reflecting on the photo. After that comes a short text by the photographer, offering additional details, such as where and when the photo was taken, the motivations behind it, and the photographer’s practice. Then, of course, there are options (more like encouragements) to comment, share, and subscribe. At some point, Iduma conducted polls to engage greater critical discussion. From March - May 2023, guest writers are invited to contribute micro-essays on any three photographs in the Substack. It is a digital and remarkably participatory archive.

The photos work by understatement, through a harnessing of absence. They hold what is not present within the frame by retaining its suggestion and echo. History is enfolded in the present. Political and social reality are seen through the personal. Sometimes we see this directly, such as in Nneka Iwunna Ezemezue’s Theresa, where a woman almost entirely outside the frame holds up an old photo to the camera. At other times, we see it implied in the objects within the frame, such as the skyscrapers in a South African city built on years of miners’ labor, or the site of an abandoned compound and the long legacy of violence and displacement it calls to mind.

<figcaption> Nneka Iwunna Ezemezue, Theresa. Courtesy of the artist. "I was the first wife of my late husband and this is the only picture I have left to remember him. The second wife burnt all the other pictures. She had the support of the villagers because she carried out the traditional mourning rites. My refusal to do it led to my being frustrated out of my late husband's house with nothing."

Of the first photo, Abeokuta Bridge Workers by Ifebusola Shotunde, Iduma writes: “The scene seems quiet, but the men in hard hats – and another who seems to be bent over a wheelbarrow – suggest otherwise. It is a setting of loud, constant noise.” Iduma’s amplitude as a writer and critic is implied here. How much tension is contained in a tender photo? How much can it hold of the soothing and unsettling? Above all, in the photos selected, there is a faith in a vision of life that never surrenders the place of the tender and intimate. They are never obliterated by brutishness or despair, however palpable.

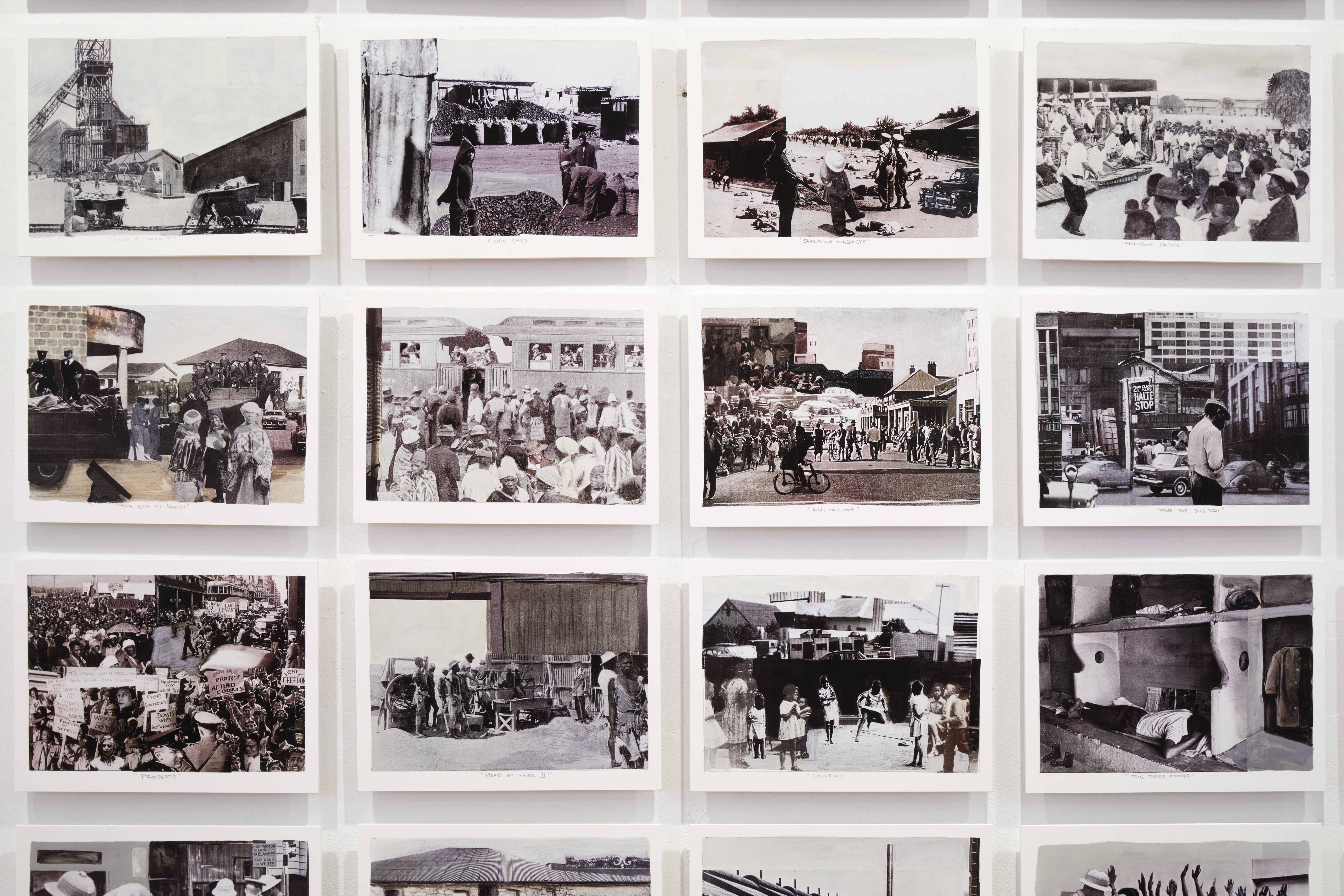

A great many photographs taken of Africans in the colonial era functioned more as studies than as photographs. Their aim was not to record beauty, dignity, personal memory, or social history; they were simply ethnographic documents, and sometimes, something a little more crude: studies in African physiognomy. Iduma has written about such photography a number of times, showing the irreducibility of the African gaze and presence. Contrary to what was intended for them, contrary to the spirit behind their production and archiving, he has found faces and people in these photographs with whom he is kin. He has, through narrative that stays faithful to an essential truth, perceived their stories and identified himself with them. In his photo essay “The Colonizer’s Archive Is a Crooked Finger,” he says: “I look at you. I remain with you.”

I feel this sentiment generally when going through Tender Photo. There is a close identification with the subjects as well as a feeling for the histories and evocations of each photograph. In drawing out kinship, the flow of time is refused linearity. In every single photo, present and past are interwoven. And through this weave shines an intimation of the future.

<figcaption> Ifebusola Shotunde, Abeokuta Bridge Workers. Courtesy the artist.

Tender Photo is a personal archive that is being built with the public. The space is generous. It allows us in and rewards us with an intimate moment. In this moment we are likely to discover something about ourselves. And even when we don’t, we find affirmation for things we may have suspected or felt. In her micro-essay on three photographs in the archive, Iyanuoluwa Adenle writes that “nostalgia is a kind of mercy.” Alvin Pang writes in his: “We who are history stand apart from history’s gaze.” Alice Zoo asks of Blessing Atas’ photograph of several feet in mid-dance: “How is it that we can tell that even these feet are joyful?” And then answers: “Such is the potency of this photograph, that a portrait without faces can tell us so much.” Some viewers of the archive are reminded of laborers, of lost love, of the tenderness of photographs, of the joy of movement; others think of what it means to witness another, of what empty spaces once held, of the affirmation in a touch or gesture, of the gift of having one another.

The work Tender Photo sets for itself is refreshingly uncommon. Public archives of African photography, besides being historical records, often serve markedly political or sociological functions. In other words, they are addressed more to an outside reality than to an interior one. Necessary as that is, it has become important to look to work that positions the archive for a different function, in ways that are not chained to the desiccation of history or the unending struggle and fatigue of politics. Iduma is doing this kind of work – and asking pertinent questions. Can a public archive privilege, not necessarily visibility, but a kind of self-knowing, a kind of being with one’s kin? Can it address itself primarily to all that is intimate?

To be sure, photographs in public archives, like nearly all photographs, possess something of the intimate. But for the most part that intimacy is only incidental, for one comes to the archive for different reasons – often for research, for a certain truth of history. Iduma’s Tender Photo makes the intimate more palpable, more central to what it is doing. An archive as a way of witnessing and holding each other. As the contemporary moment unfolds, Iduma’s curation asserts a confidence that there is a way to be free of history’s imprisoning frames while we remain within its tender gaze.

tenderphoto.substack.com

Joseph Omoh Ndukwu is a writer and editor living in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Read more from

Introducing the C& Cyclopedia

The Art of Dialogue: Living Archives, Memory and Practice

C& Builds a Living Digital Archive

Read more from

Can African Critics Rewrite the Story of African Photography?

History is contemporary, and is happening now