Dakar OFF carves out its own spaces of engagement

The biennial implies a “radical re-inscription of the artist-subject as a model of global citizenship and (upward) mobility,” writes Simon Sheikh in his essay The Artist as model Subject, and the Biennial Model as Apparatus of Subjectivity, recently published in the Manifesta Journal. His term ‘biennialized’ – suggests the way in which artists are inserted into …

The biennial implies a “radical re-inscription of the artist-subject as a model of global citizenship and (upward) mobility,” writes Simon Sheikh in his essay The Artist as model Subject, and the Biennial Model as Apparatus of Subjectivity, recently published in the Manifesta Journal. His term ‘biennialized’ – suggests the way in which artists are inserted into global flows of capital; circulated, presented and represented in a complex network in which their subjectivity is easily transformed into commodity, and the local dissolves in favour of the ‘international’ – that prized category. During my visit to Dak’Art, Sheikh’s ideas about stylisation, capitalisation and internationalism kept returning to me, particularly when I tried to understand the relationship that the official biennial and its theme – Producing the Common – had to the sprawling mass of exhibitions which accumulated as OFF.

Perhaps inevitably, this biennial’s focus – influenced by Michael Hardt’s essay on the production and distribution of the common – was concerned with broad ideas: of politics and aesthetics, and “the merits or demerits, if you like, of Universal Civilization in light of contemporary cultural production and globalization.” In its concern with that which is shared, that which transcends locality and specificity, the biennial tugged at the strings that tied it to its own location in the north of Dakar on the Route de Rufisque, a long, busy and dusty road out of the city.

But it is here that the biennial’s messier, louder and more outrageous sibling event, OFF, plugged some of the holes which the biennial, perhaps necessarily, left open. With over 200 exhibitions across the city and satellite events in Saint Louis in the north of country, the Lac Rose, the town of Thies, and Ziguinchor in the Casamance region of Senegal, OFF is overwhelming in scale. Exhibitions were listed in a folder of 7 pamphlets, detailing 230 separate locations and events. Exhibitions were held in the most brilliantly prosaic of locations: the general hospital, restaurants, hotels, bookshops, bars, schools, cultural centres. In the Piscine Olympique (home to CCA Lagos’s roving alternative art school, Àsìkò), zoological parks, and an old biscuit factory. Anywhere and everywhere. But occasionally, the search for OFF felt like an endless chase, designed to lure unwitting foreigners in their folly search for art into the maddening trap of midday heat and traffic of inner-city Dakar.

The scarcity of arts spaces in Dakar means that OFF – if it is to keep its promise to “protect[ing] the spirit of freedom,” as the founder Mauro Petroni told this magazine – has to spread itself across the city, to carve out its own spaces of engagement where it can. As such, it feels driven by a sense of improvisation, and of spontaneity. It is utterly un-precious about art, open and embracing of amateurism and open too to the reality that a lot of the art is bad. “Still,” say Petroni, “it has always been pretty effective at making young people live, work and dream, and there have always been a small number of good shows that restore full meaning to the event.” I’ll resist entering into a discussion of Roger Cardinal’s problematic term “outsider art”, for fear of repeating the many conversations initiated by the Encyclopeadic Palace at last year's Venice Biennale, but OFF’s relationship to IN invigorated similar tensions. Who is on the outside, and who is inside? How does the fringe disturb the canon, and where do we draw the line between the professional and the amateur, particularly in a country where provision for arts education and practical support is almost non-existent?

One afternoon, stumbling around the grounds of the Centre Hospitalier de Fann in search of a screening of animations made by a small group of psychiatric patients, the points of connection and convergence that art can offer – in often strange, sometimes awkward pathways to communality – felt particularly powerful. In a white-tiled roomed set against one of the perimeter walls, a projector, some snacks and a few plastic chairs formed the auditorium for the showcase of works of a collaborative project between the Clinique Psychiatrique de Moussa Diop and a Belgian cultural initiative. The films were elegant. Delicate line drawings assembled into quivering shapes; voice-overs spoke poetic, dark narratives; black paint bloomed and spilled onto glass sheets and fingers smeared symbols and colours into strange, ominous clouds. The words “Lou beauth khayma” were repeated, like a mantra, throughout and although I still have no idea what that means it has stuck with me.

From the hospital, I took a taxi across the city to the Plateau, in search of the legendary Senegalese artist Issa Samb’s open studio on Rue de Jules Ferry, which he’s kept and filled with objects, art works and frankly, stuff, for over 40 years. The space feels like an open sketchbook – not dissimilar to Sir John Soane’s quixotic crypt to memory and architectural research in London. A carton of orange juice long ago forgotten sits opposite unfinished canvases propped against crumbling walls. A web-like mass of objects hanging from strings and ropes form the centrepiece of the space, decorated with dolls, bits of metal and chain, snippets of exposed film, and strips of ragged material. A makeshift shrine to an unknown man smoking a cigarette finds a pedestal in Bruce Bernard’s Century: One Hundred Years of Human Progress, Regression, Suffering and Hope, a fitting title for this space. Beside it hang hand-painted posters made for a public performance Plekhanov plays in the 1970s, which members of the artist collective Laboratoire Agit-Art had performed in, and of which Samb was a founding member. The collective’s aim, to agitate existing institutional frameworks, and to “critically promote the development of cultural and artistic endeavours, whose goals were to blur disciplinary boundaries and to propose the experience of a ‘total art’ […] influenced by vernacular cultures and languages” felt very much re-activated by OFF’s ethos. In fact, Samb’s atelier could be a microcosm of OFF itself – messy, seemingly impulsive, but pertinent, at times beautiful, and provocative as well.

.

<figcaption> Senegalese artist Issa Samb’s open studio on Rue de Jules Ferry.

.

Various hunts across the city, from the dense Plateau to the wide, blustery Corniche uncovered more unexpected and rewarding finds. In an upmarket restaurant I awkwardly made my way around lunchtime diners sipping chilled white wine to see Mamady Seydi’s sculptures. Minotaur-like figures made from cast bandages bucked and jumped in the corners of the room, in poses both sexual and droll. Nearby, Barkinado Bocoum’s large-scale paintings combined a pixelated and vivid geometric style with figurative intrusions on the canvas, a cut-and-paste approach to painting echoed by a number of other artists exhibiting in OFF, perhaps referencing the rise of internet and digital technologies in Senegal and across the continent. This contrasted with the paintings of Cheikhou Ba exhibited at the Villa Racine on the next street over, which returned to a familiar style, strongly referencing Basquiat (as did many others), in a more abstract, recognisable manner. Judging by the number of red dots beneath the works they proved popular with collectors. Downtown, at the Restaurant Big Five, photographs of the colossal Mbeubeuss dump outside Dakar hung above tables set for dinner service. The images showed the smoking, seething mass of waste upon which many women and children work. The uncomfortable reminder of the excesses of consumption were not lost on the owner, who smiled ironically at his ad hoc exhibition space. Up by the city port, at the Eiffage headquarters – a major Senegalese construction company and the main sponsor of OFF – Ousmane Sow’s giant figures sat, squatted and reclined lazily in the building’s central court, their rough dark-mud skins appearing brilliantly alien against the smooth tiled floors, while clerks and besuited men scrambled around them. Incongruity was the hallmark of OFF.

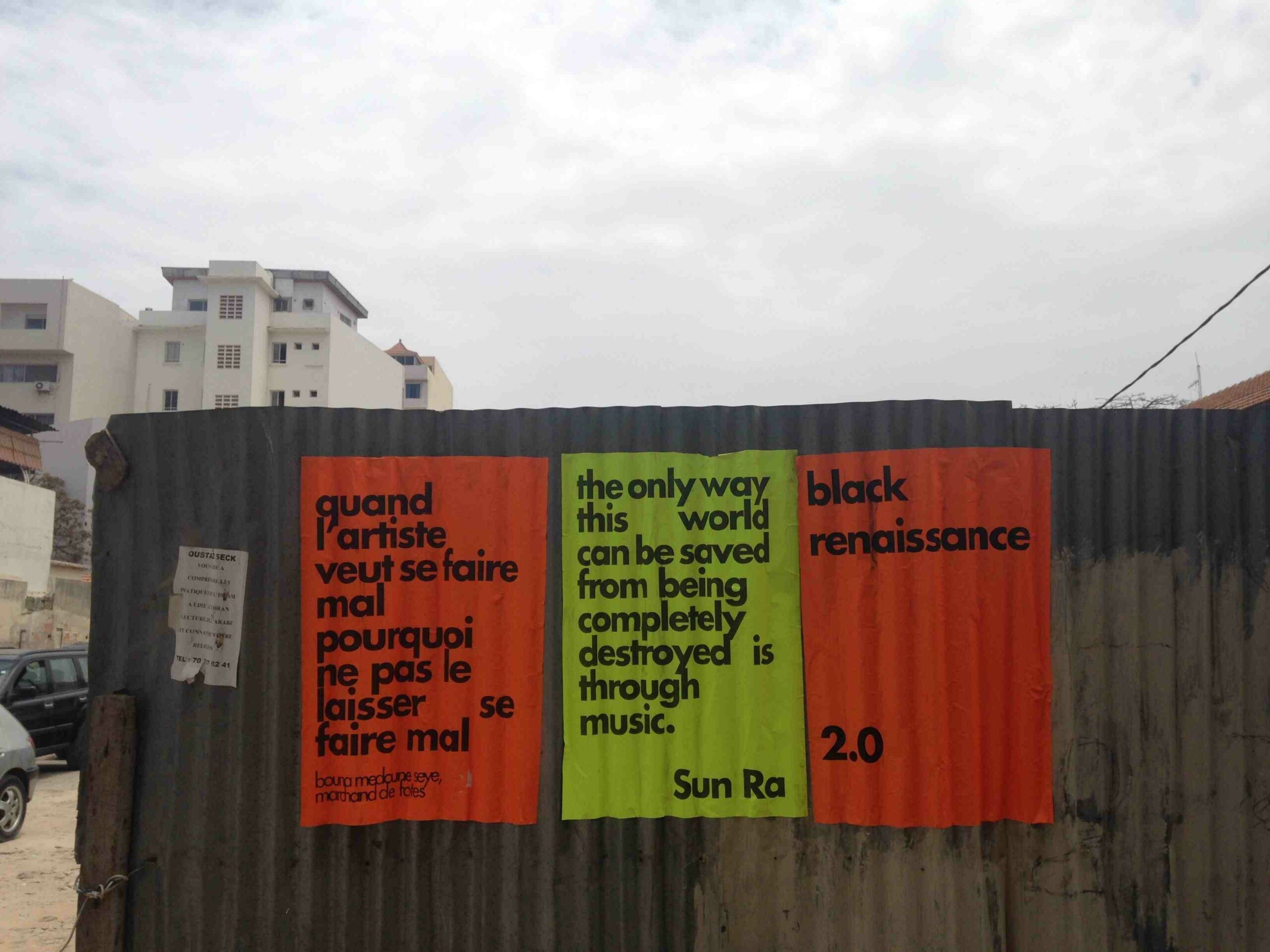

Other highlights were found further afield. In La Biscuiterie, an old biscuit factory now home to artist collectives, clubs, and a 3D cinema three exhibitions in a giant hangar departed from the ubiquitous offerings of painting and sculpture. In MoreHuman, small documents, photographic works and an Afrofuturist manifesto decorated the walls. A beautiful text-based work printed on a fine, opaque paper by Joel Andrianomearisoa was pinned delicately to the brick wall, bleeding English to French and pop phrases to poetry: The project was based on the "Afrikadaa Street Publication" and involved the Senegalese public by making segments from the publication visible in common areas of the city. Next door, the dinner table as a microcosm of relations between the individual and society were theatrically explored in Maimouna Guerresi’s M.Eating series of photographic polyptychs. An adjacent exhibition by the Les Ateliers Sahm artists from Brazzaville displayed resourcefulness and visual flair. In Francis Koudia’s photographs, women and children hold baskets above their heads, their faces covered in dappled, grid-like patterns, their eyes upturned to the sky. Doctroveé Dansimba’s Dem Dikk, Morceaux de verge (2014) used shattered glass from city buses to form a vague map-like territory scattered across the cement floor.

At Raw Material Company, Precarious Imaging: Visibility Surrounding African Queerness asked about the consequences of visibility when it incites violence against a gay minority. When I visited, the lamps and facade had been vandalised during the night, and shards of plastic and plaster had been collected in small piles outside the entrance, making the exhibited works by Kader Attia, Zanele Muholi, Andrew Esiebo, Jim Chuchu, and Amanda Kerdahi all the more urgent. A little way across town, Kër Thiossane – a multimedia centre set up in 2002 to provide local artists and musicians with access to digital and multimedia tools – was home to Afropixel 4, a digital festival running workshops on sampling, video mapping, open source software and testing the ground for an alternative currency prototyped locally by Mansour Ciss.

I could mention much, much more. But part of OFF’s charm was the sense that you could only ever access a small part of it; that despite long days in search of the bright blue signs which announced an exhibition, you could only scratch the surface. The questions OFF asks, about the position that untrained, or unconventionally trained artists have to the small, but growing market of African art, and what the value of their parallel but separate position to IN might be, remains unresolved. Perhaps OFF is the anti-biennial, priding itself on magnanimous inclusiveness, but bordering on carelessness. Perhaps it’s a working manifesto for ad hocism. Frustrating, overwhelming, but a powerful provocation: OFF’s spirit of improvisation is a vital counterpart to Dak’Art, and one which extends the engagement of art out of the gallery into the dustiest corners of the city.

Basia Lewandowska Cummings is a London based editor, writer and film curator.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission