Cultural Development Policy

6 November 2019

Magazine C&

6 min read

“Fifteen years of international exchange of contemporary art,” reads an exhibition flyer I am holding in my hands in amazement. I am at the Bundesarchiv Lichterfelde, just now becoming aware of the scope of the tasks that the East German Zentrum für Kunstaustellungen (center for art exhibitions) had to cope with. Between 1973 and 1988, …

“Fifteen years of international exchange of contemporary art,” reads an exhibition flyer I am holding in my hands in amazement. I am at the Bundesarchiv Lichterfelde, just now becoming aware of the scope of the tasks that the East German Zentrum für Kunstaustellungen (center for art exhibitions) had to cope with. Between 1973 and 1988, around two thousand exhibitions were created in cooperation with over ninety countries, the leaflet reports–some of them abroad in the so-called brother countries, most of them at home in the GDR.

The founding of the Neue Berliner Galerie – Zentrum für Kunstausstellungen der DDR in 1973 replaced the provisional exhibition group that had previously worked on conceptualizing an exhibition system for the GDR. Other key exhibition venues would include ethnological museums, art academies, the Galerie am Weidendamm, and the Galerie am Fernsehturm. According to art historian Romuald Tchibozo, the reason official exhibitions were not held regularly until the 1970s is that the GDR’s foreign relations were initially characterized primarily by political and economic factors.

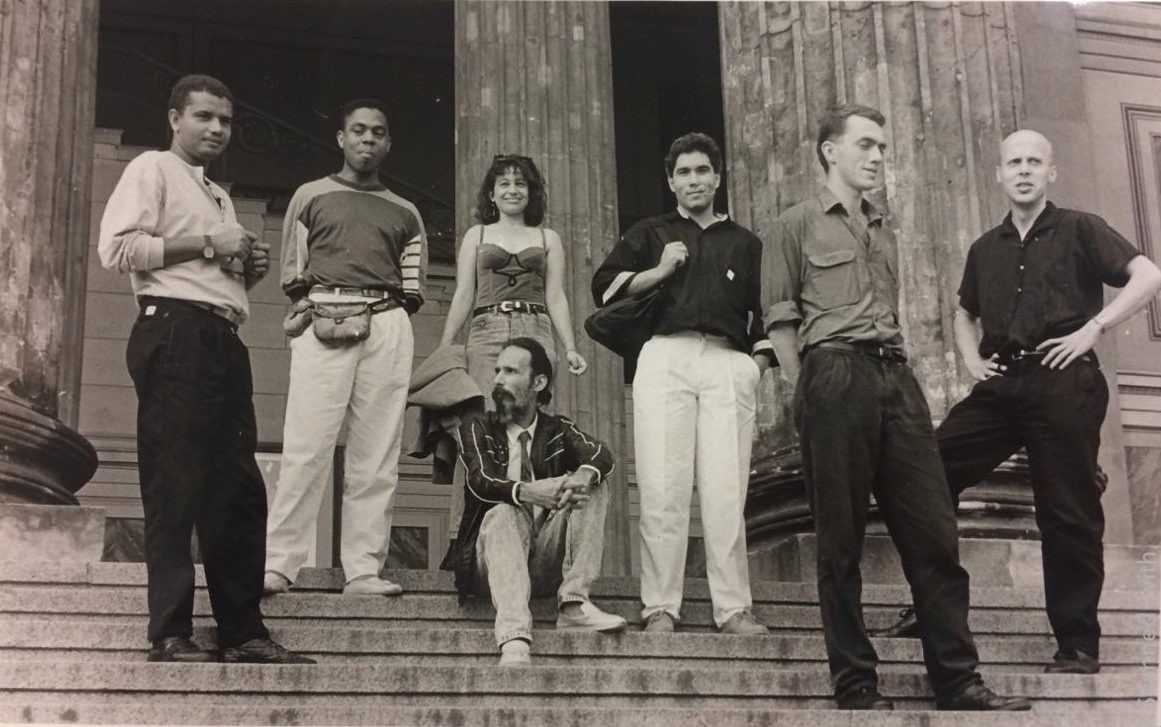

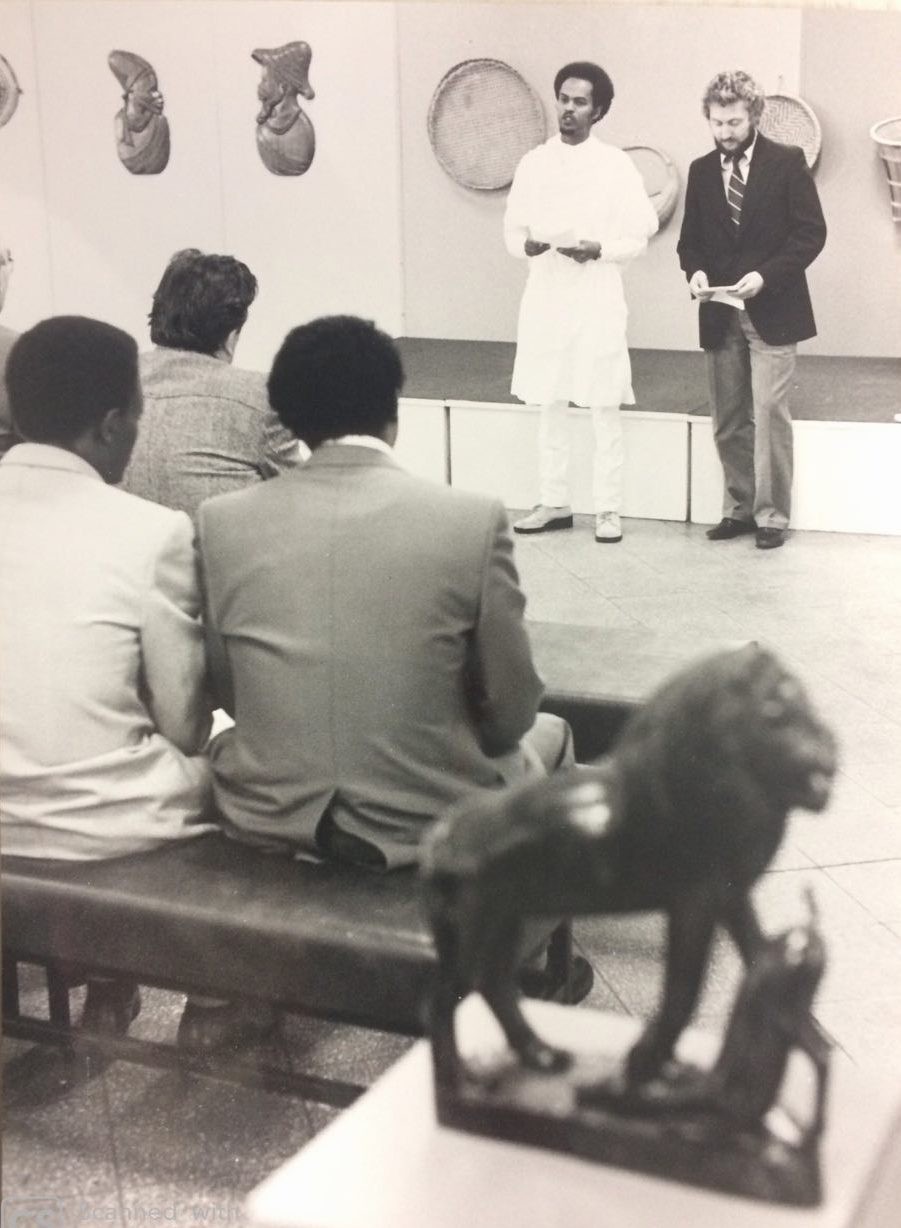

Opening of the exhibition Fine and Applied Art from Angola, Ethiopia, Madagascar and Mozambique, 1980. Photo: Wolfgang Schönborn. Courtesy of the Bundesarchiv Lichterfelde

At first, the aim was to gain stability and international recognition, especially in competition with the capitalist countries, above all West Germany. A report by the Central Committee of the ruling East German Communist Party on the period from 1963 to 1971 sheds light on attempts to establish relations at the cultural level:

“In most cases, this development is combination [combined] with the effort to eliminate the art-hostile influences of Western countries. Cultural foreign relations must follow up on this and, in conjunction with information about cultural development in the GDR, give these countries effective support in their efforts to overcome the colonial legacy in the cultural sphere and the influences of modernism that are detrimental to the development of their own national culture. In this context, West German activity can also be effectively countered. Positive experiences gained in this respect in the UAR [United Arab Republic] must be purposefully applied in other countries as well.” 1

The cultural sector was clearly being assigned a task here. Despite a proclaimed resistance to the colonial legacy through art and culture, the rhetoric used is strongly reminiscent of missionary ambitions. The aim was to help other countries achieve “socialist progress” by spreading the GDR’s “cultural development.” And although the report speaks of self-determined “development,” we know that GDR officials expected artistic production to have a socialist style. In general, official GDR exhibitions abroad were intended to offer insights into either everyday life in a socialist setting or the country’s artistic production. Zanzibar, the first goal of the GDR’s “commitment” in East Africa, for example, hosted an exhibition on Käthe Kollwitz in1967.

Inside the GDR, exhibitions ranged from surveys of contemporary artistic positions to ethnologically inspired retrospectives of so-called ancient art. The 1980 exhibition Kunst aus Afrika, showing visual and applied arts from Angola, Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Mozambique, represented an attempt to combine the two. Most exhibitions focused on a specific country and occasionally a specific medium, as for instance in Künstlerische Fotografie aus Mosambik (1983). There were also some group exhibitions, such as Junge Künstler der DDR und Kubas (1989).

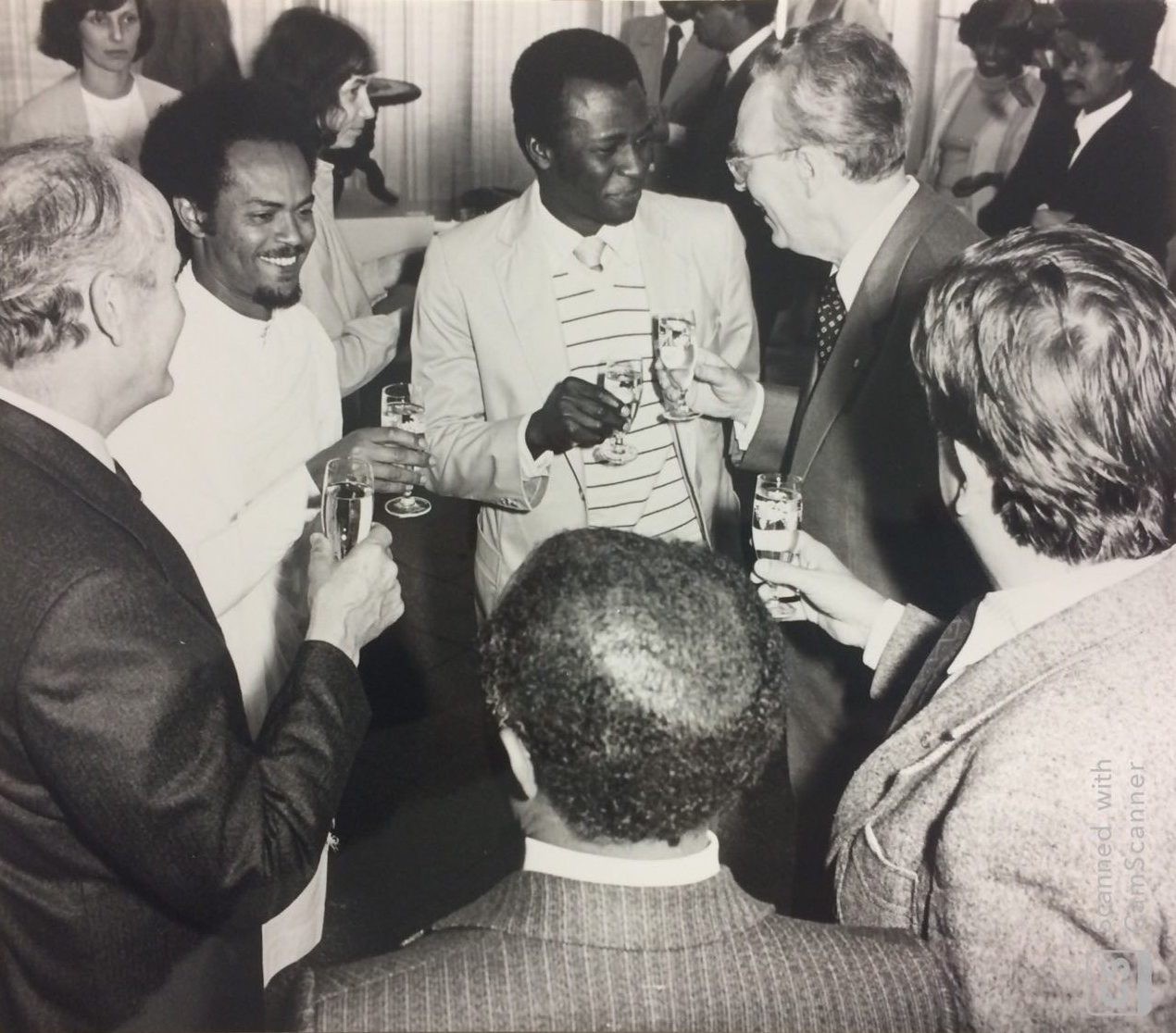

Individual exhibitions were rarely organized, but two retrospectives of Mozambican painter Valente Malangatana Ngwenya, in Leipzig and in Berlin in 1986, received much attention. Ngwenya became an icon, known not just for his artwork but also for his political activism–above all for his incarceration in 1964 because of his membership of the liberation front FRELIMO2. In the accompanying catalog, the exhibitions were described as a highlight in the friendly relationship between the GDR and Mozambique. His works were meant to contribute to a better understanding among the East German population of the struggle against South Africa’s apartheid regime, including the political developments in Mozambique and their own country’s involvement. The GDR supported FRELIMO in the struggle against RENAMO3, an anti-communist resistance movement in the newly independent socialist state which was supported among others by the South African apartheid regime.

The reception of Valente Malangatana Ngwenya points at the significance of the GDR’s exhibition practice. The wooden sculptures made by the Makonde people are another example of the linkage between art and politics; their themes can be understood in close connection with the political philosophy of Ujamaa4, conceptualized by the first president of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere. Nyerere advocated a socialist model of society that included the collectivization of agriculture and the nationalization of banks and industries. Commissions from FRELIMO commissions also gave Makonde wood art new inspiration, creating satirical representations of Portuguese colonial rulers. As the GDR advocated struggle against the imperialist powers, Makonde sculptures thus became popular exhibition objects there.

Opening of the exhibition Fine and Applied Art from Angola, Ethiopia, Madagascar and Mozambique, 1980. Photo: Wolfgang Schönborn. Courtesy of the Bundesarchiv Lichterfelde

The political objectives of the exhibition system also become apparent in the traveling exhibition Traditionelle Kunst aus Äthiopien, which opened in Berlin in 1986 on the twelfth anniversary of the Ethiopian Revolution. It was subsequently shown in the cities of Dresden, Minsk, Warsaw, and Moscow and was intended to strengthen and expand Ethiopian ties to the Eastern bloc.

The material I found in the archive testifies to the regular correspondence between the diplomatic missions. These include requests for internships from young Ethiopian students, as well as reports of paintings lost at Schönefeld Airport.What strikes me, however, is that there is often a lack of evidence to show how those involved were affected. I would like to learn more about the participating artists and their perspectives, and about moments of actual interpersonal exchange.

One thing, however, has already become clear to me through my involvement with the exhibition practice of the GDR: it’s worth researching archives. Obviously, archives provide a mediated account of historical experience. Nevertheless, they provide opportunities to revise the established canon of historiography, to facilitate changes of perspective, and above all to make visible the forgotten actors.

By Jule Lagoda.

1 SAPMO-BArch, Schlussfolgerungen für die Kulturellen Beziehungen zu den jungen Nationalstaaten, SED ZK, p. 34, quoted in Romuald Tchibozo, “L’Art d’Afrique dans l’ex-République Démocratique Allemande: Entre influence idéologique et légitimation,” Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal 1, no. 1 (2014).

2 Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Mozambican Liberation Front).

3 Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (National Resistance of Mozambique).

4 Ujamaa is Swahili for family or community spirit.

from

Essay

The Museum of Black Futures

Caribbean Sounds: The Connective Possibilities of Radio

Black Canadian Print Cultures: Of Quiet and Enduring Legacies

from

Political art

Art in Support of Political Change

Hungarofuturism and its Parallels with Afrofuturism