Bodies Speaking: A Generation of Feminist Artists

The exhibition Body Talk that ran at the Wiels center for contemporary art in Brussels, and is currently showing at Lunds Kunsthall in Sweden, brings us into a discursive space where we are asked to consider the mobilization of the body through the works of six artists, Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Marcia Kure, Miriam Syowia Kyambi, Valérie …

The exhibition Body Talk that ran at theWiels center for contemporary art in Brussels, and is currently showing atLunds Kunsthall in Sweden, brings us into a discursive space where we are asked to consider the mobilization of the body through the works of six artists,Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Marcia Kure, Miriam Syowia Kyambi, Valérie Oka, Tracey Rose, and Billie Zangewa. Two issues are at the core of this group exhibition. The first is to present a generation of female artists, trained in the late ’90s, who use the body as a medium of expression in their art, but also as a vehicle for their activism. These topics update the questions of feminism as well as the concepts of identity surrounding sex and gender. The second objective is to make visible contemporary African art in relation to the cultural diversity of the continent, with a large number of different artistic statements, including the Diaspora as a factor in its own right. The curator,Koyo Kouoh, asks us, “What is a female African body? How did it become and continue to be perceived socially, historically, and politically as an object, a body (over)exposed, abused, and used?”

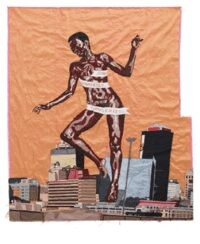

Billie Zangewa, The Rebirth of the Black Venus, 2010.

Tapisserie de soie 127 x 130 cm. Collection privée.

Entering the exhibition, we come face to face with the two-dimensional work of Billie Zangewa, The Rebirth of the Black Venus. This “silk tapestry,” as the artist calls it, is inspired by Botticelli’s ‘The Birth of Venus’ and the tragic story of the Black Venus ‘Saartjie.’ These two examples of the body as object illustrate, by their asymmetry, what promotes an imperialist, universalist, socio-normative, and racist discourse in western representations of images of feminine beauty. Written on the cloth that covers the genitals of the depicted body is the statement, “abandon yourself without reservation to your own complexity.” This reinvention of the self-portrait positions the artist between the collectivity of the entire history of representations of the body and the affirmation of her own personal narrative. She questions and reverses the basic fundamentals of identity that allow one body to be seen, while making others invisible. The artist invites viewers to question their own culturally constructed realities, which are still rarely criticized in terms of the mystification the history of art maintains about the esthetics of the body and its issues. Appropriation stands out immediately as a central theme of the exhibition. It is the starting point for a critique of the norms of recognition that are too often accepted as natural. If performative acts seek to change reality rather than to describe it, following the argument of Paul B. Preciado, then it is through the reappropriation of performativity that we can reconstruct subjectivity (1).

<figcaption> Miriam Syowia Kyambi, Fracture (i), 2011. Multimedia-installation / performance. Photo: Marko Kivioja, Terhi Vaatti en Anni Kivioja, Kouvola Art Museum Poikilo, Finland. Courtesy of the artist.

Subscribing to this logic, the first part of the exposition underlines the importance of performance as a mechanism for dissent. With her multidisciplinary installation-performance piece Fracture/Rupture, Miriam Syowia Kyambi uses her body to act out repetitions of a social ritual, showing how individual identity is shaped through norms. The artist embodies a contemporary character, named Rose, representing the figure of the female consumer realized in Kenya. This character evolves throughout the piece in an installation built up of various objects that refer to aspects of her own personal past. The performance takes shape through manipulation of objects, a meeting of animated body and immobile body, between present action and a narration of the past. By reinforcing Rose’s social identity, Kyambi exposes the performative power that legitimizes it by totally concealing historicity. The performed body is seen both as a provocation and a trigger. The mirror, a recurring object in Kyambi’s work, reflects the viewers’ perspective, integrating them into the installation and inviting them to take a stance.

Valérie Oka, Body Talk Deshumanisation, 2014. Installation, La cage and performance, En sa presence . Avec l'aimbale autorisation de l'artiste.

Valérie Oka conceives of her art as an appeal. She makes the exhibition into a space for dialogue. With En sa présence and Cage, switching between performance and installation, the artist tries to sensitize the audience to the idea that removing identity from oneself can reconstruct the subjectivity damaged by dominant performativity (2). The spectator first comes across a dinner table. He or she sits down, picks up the headphones and watches a screen placed between the plates. The screen shows how this scene is constructed by the guests who play a part in it. During the opening of the exhibition, the dinner took place at the same time as the performance Cage, and together they created a discursive alternative to the question: “How is the Black woman represented by the White man?” Red neon writing on the wall asks, “Do you really think that because I’m Black I fuck better?” All through this debate there is constant dialogue intended to analyze and deconstruct the clichés and stereotypes imposed on the black female body in the collective imagination as products of colonial fantasy.

Tracey Rose, Tracings (detail), 2015. Installation. Courtesy Dan Gunn, Berlin and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg. Photo: Joke Floreal.

Bodies under examination are also shown in the video projection Tracing by Tracey Rose. Confronted with the work at the end of the long, narrow corridor in the middle of the exhibition, the viewer is tossed around in a game of twisted perceptions and scales. The performer’s body is, at different times, monumental, close, far away, and distanced, shifting between an intimate conversation and an intimidating face-to-face confrontation. The sound from the video reverberates through the entire exhibition, sometimes loud, with the artist nearly screaming, sometimes thin and exhausted, almost detached from itself. Pushing her voice to the extreme, she goes beyond the limitations of her body, of power itself. The various camera perspectives shift from the artist, in the midst of her performative pilgrimage, to the overall shot of the total ritual being enacted. At the foot of the tomb of the Belgian royal family inside the church of Notre-Dame, the artist condemns the horrors perpetuated by colonialism in Africa. The scream here is central to the body’s performance. Physical exertion symbolizes very aptly the act of subversion/empowerment that Audre Lorde identifies in her poignant text “The Transformations of Silence into Language and Action.”(3).

Through these artistic and contemporary cultural actions of body, gender, and politics of sexuality, Body Talk is a call for collective resistance against the invisibility of female artists from Africa and from the Diaspora. Art is presented here as a tool for reenactment that can spread ideas, inspire action, and raise consciousness to a new level. Perceptions and the flow of representations of the body vividly involve each of the artistic processes shown here in a dynamic, mobile, and interactive dialogue. It is, however, very important to point out that violence not only channels through the forms of representation, but exists also in the way we look at, perceive, and receive these forms. That is why we owe it to ourselves to take the impact of these standpoints as a corollary of their reception.

The exhibition BODY TALK - FEMINISM, SEXUALITY AND THE BODY IN THE WORK OF SIX AFRICAN WOMEN ARTISTS runs until September 27, 2015 at Lunds konsthall , Lund, Sweden

Elsa Guily studies art history and is an independent critic living in Berlin, specializing in the relationship between art and policy.

(1) Paul B. Preciado, [in French] “Force d’attraction de la rupture". 29/08/2014

(2) Idem.

(3) Audre Lorde. “The Transformations of Silence into Language and Action.” In Sister Outsider. The Crossing Press, 1984.

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission

Paris Noir: Pan-African Surrealism, Abstraction and Figuration

Review

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

Werewere Liking: Of Spirit, Sound, and the Shape of Transmission