As you all know we are celebrating the launch of our first C& Book. On the occasion of the C& Party with amazing tunes we were featuring one of our favourite artists: Afro-Mexican Rapper Macandal

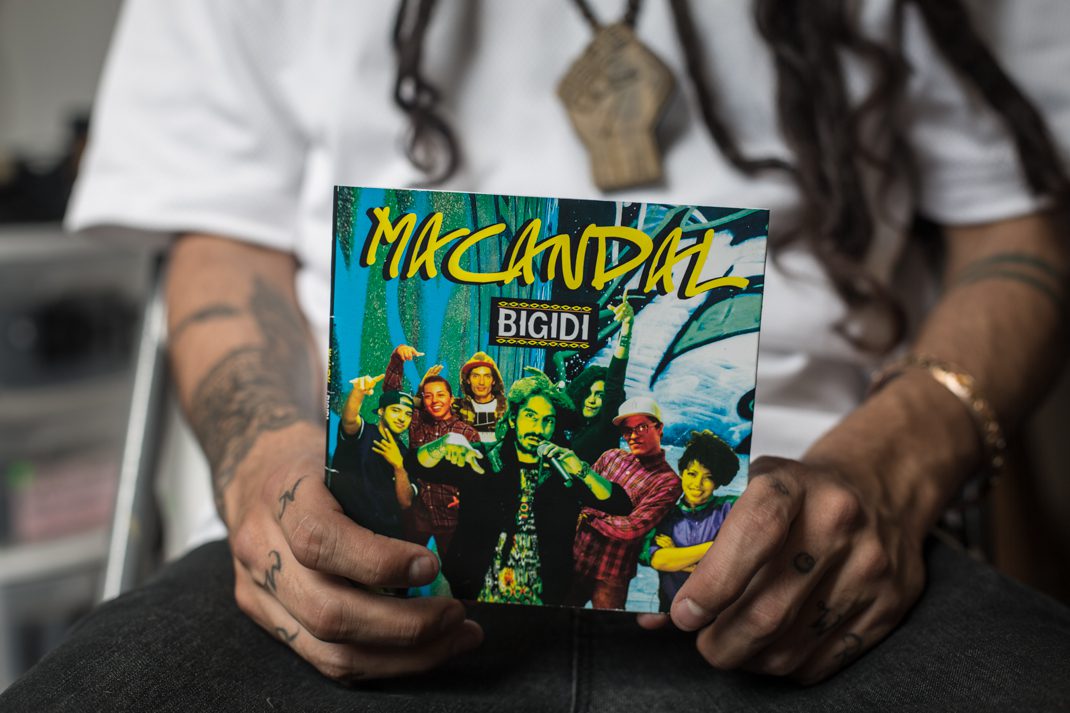

Macandal's album

Background

“Before 2009 I was working with the Rastafari community in Mexico. My life was completely Rasta and Rastafari has always been an anti-colonial resistance movement. In 2012, in the middle of the political events at the time (presidential elections in Mexico), I became interested in certain Latin American philosophers and in certain musical groups that represented those critical reflections on colonialism.

I wrote Moretnidad between 2010 and 2012. My personal growth meant that it was impossible not to be influenced by the political situation, there was a national fever. The lyrics are based on current events.

Starting with what the colonial situation was and what decoloniality was, it was simply about reading, analyzing, and if something flowed from me it was because of my time with the Rastafari movement. In Moretnidad, I was relearning a lot of things, thinking about them from a more critical perspective. Bigidi is a recent work, another process in my life, one of much learning, of more transcendent critical thinking.”

Heriberto Paredes: In Mexico, it seems like recognition of the Third Root or Negritude is growing each day. Do you agree and do you think it has influenced your work?

Macandal: Obviously, we live in a creole nation with very white values. Racism always becomes more sophisticated, institutions are very sophisticated in this sense. Nowadays we start to speak out about Africa and the Third Root, festivals wanting to reclaim and make this visible are being organized but not at all to empower, that is also problematic. It is not that people do not hear about it, it is just that the way they hear about it is very folkloric. Something distant from us. We are living an identity full of creolisms, of a white mix that completely excludes negritude. It is important to find responsible ways to bring attention to and empower those discourses. Today, people are beginning to feel closer to Africa, but we have to look for more effective methods, so that people are able to identify with the discourse I am talking about. On this album, Bigidi, I am upholding this discourse and also inviting people to dance, it’s an album you dance to. I am looking for a way to empower Africa and indigenous peoples.

HP: Where does the name and concept of Bigidi come from?

M: Bigidi comes from the “Semillero del Caribe” [Hotbed of the Caribbean] (developed by Minia Biabiany, Madeline Jiménez and Ulrik López in February 2016 in Mexico City). I did not know about bigidi, but learned it is a dance from the island of Guadeloupe, where the dancers seem to fall or be intoxicated. Obviously, I do not have the cosmogony to be able to understand in depth what bigidi is but I can say bigidi made me think about balance from another point of view, beyond duality, which is the Western perspective where we must always be balanced. In bigidi, balance is different. We are always in crisis: economic, emotional, existential, identity. Speaking personally, realizing there are different types of balance was a great relief. At the time I was producing Bigidi, many things were changing in my life and I understood it was not an imbalance, but another kind of balance. That is why I named the album Bigidi. Besides this, there is a connection with the earth. When dancing bigidi, you are connecting to and exalting life.

HP: You spoke about this album being a work that motivates dance, that this is one of its central characteristics. Can you tell me about the development of this album and what other characteristics it has?

M: The beats, from the beginning, were intended for instrumentals that would allow the body to move, that would invite you to shake your body, because that is exactly my positioning. Above all, decoloniality talks about corporal reappropriation, so dance is a corporal reappropriation, a few minutes of glory, even if subjective. Besides, dancing is ageless. The lyrics talk about personal issues, but obviously I understand that what is personal is political. From a critical perspective to a social critique of what we see and what we are living in the panorama. But I am trying to be responsible with each line, wanting to invite the development of critical thinking, it is not that I want to teach something. The lyrics talk about having respect for the legacy of our indigenous peoples and invite the audience to analyze the gaze towards ourselves and towards the periphery. There is a colonial placebo in our psyche, we have been programmed to look at ourselves from the same colonial perspective and obviously at those above us as well as periphery populations. It is an invitation to examine this, because perhaps we continue thinking like the plunderer.

HP: This is about a musical project with various individuals participating throughout…

M: It was really a meticulous selection, I wanted to invite people I identify with and whom I have worked with, people who also inspire me, and people I found meeting them was very relevant . There is Rebeca Lane, whose work speaks for her; also Nativa from Costa Rica, who has a very important project there and whom we had the chance to organize an event with; and Imma Soul from Chetumal, Quintana Roo, who has a project with Bocafloja and is currently releasing an album called Sur. Imma Soul and I have run into each other at various events, her work is also decolonial, and we listen to each other’s music. Elton from Leones Negros is also part of the project, he is a member of a Queretaro sound system and ska group and they make decolonial music, strongly reclaiming the roots of indigenous peoples. Finally, Alma Beat is part of a rap group from Mexico City called Son Fino, and I like the quality of their music.

I know most of the people who produce: Dany B from Quilombo Arte; Neutra, with whom I worked on Fuera de Servicio; Facto, the majority of beats are his; and Best Quality.

HP: Could you tell us a bit more about this seminary, or “Semillero,” that provided you with new perspectives and proposed elements of reflection you had not yet considered?

M: The Semillero showed me a very interesting perspective on rap. Bigidi was something very interesting. Afro-Caribbean thinking invited me to think beyond the words and lyrical meter, the voice and intention of my words, to assimilate my voice like a drum, that as a rapper I did not understand. There is a more libertarian question in so much cimarron rebelliousness. I prefer to identify myself with this perspective than with anarchy. Although similar, these concepts are different in context and historic processes. There is a hunger to develop critical thinking. This was what had the strongest impact on me from the Semillero.

.

Heriberto Paredes is a Mexican Journalist and photographer examining resistance histories.

More Editorial