Mebrak Tareke takes a closer look at Jean-Michel Basquiat's personal and artistic archive shown at the Brooklyn Museum.

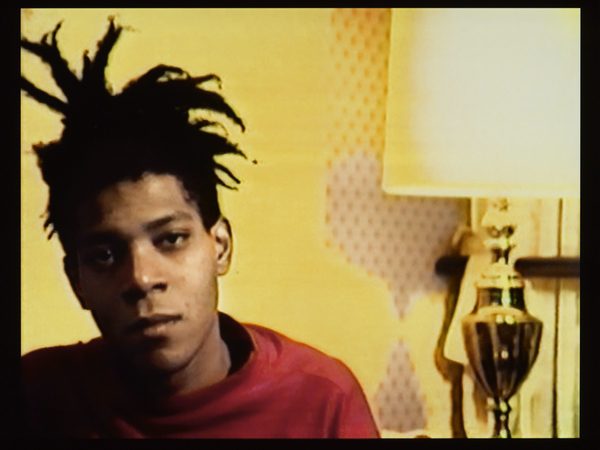

Tamra Davis, Still from A Conversation with Basquiat, 2006. 23 min., 22 sec. ©Tamra Davis. Courtesy of the artist. By permission of the Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, all rights reserved. Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum

The Brooklyn Museum’s current exhibition Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks, which runs until the end of August, features eight notebooks that contain previously unseen words and drawings from the 1980s made by Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), alongside some larger works containing text, drawing, collage and painting.

Although it has been nearly 30 years since Basquiat finished these notebooks, at first glance, they appear strangely new. These inscrutable works on paper look rough, miniscule and irrelevant. Nowadays we might be inclined to skim through them on our iPads, barely even bothering to take a closer look. They appear to be missing from a larger jigsaw puzzle, offering us a rare glimpse into the life and times of one of New York’s most intriguing young artists. By the 1980s, Basquiat had delved into Pop Art, the Punk era, Hip Hop and the city’s roaring art scene. He went on to create some of the most iconic Neo-expressionist works of the decade.

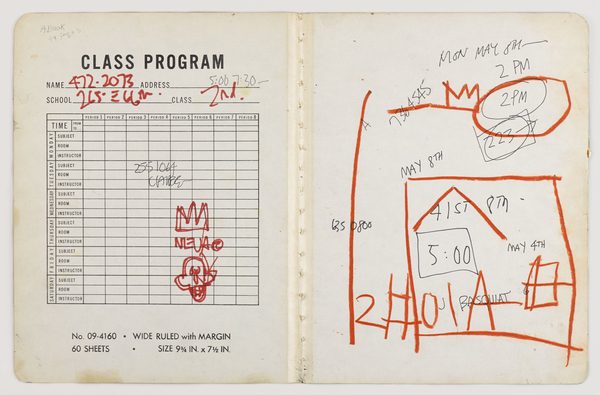

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled Notebook (inside cover), 1980?81. Mixed media on board, 9 5/8 x 15 in. (24.5 x 38.1 cm). Collection of Larry Warsh. Copyright © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, all rights reserved. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum

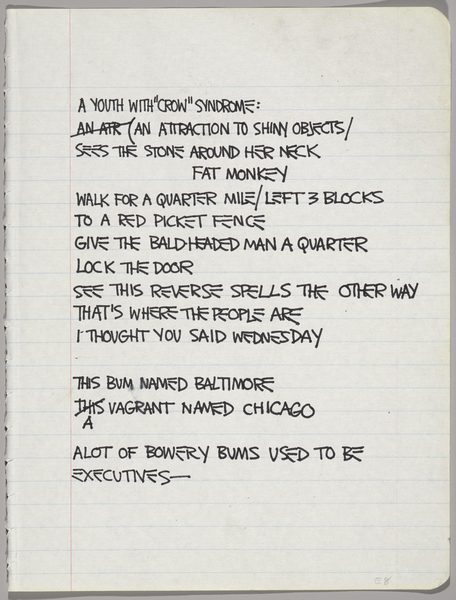

These notebooks look like pages torn out of a book. They are either encased in glass cabinets or pegged to white walls. A closer look reveals at least two things: firstly, how Basquiat constantly relied on disjointed words and haphazard drawings to create a fractured narrative, and secondly, how lone words on paper can be either a fragment of a whole or stand as independent works. Using disjointed words, Basquiat intertwined anatomy, Hip Hop and ancient history to create a narrative collage about his angst, science or racism. Constantly exploring the idea of text being radically reduced, these notebooks make us realize that words such as Landmines, Our doing or Millionaire can mean a number of different things depending on the time or place, or, whether they function as lone texts or as part of other words on a wall.

For Basquiat, language and drawing were inextricably linked. His artistic practice was just as much about language as it was about drawing. He constantly blurred the lines between writing and drawing as well as between drawing and painting. The intricate relationship between art and writing can be traced in these notebook through the function and meaning of words and, by blurring the line between fact and fiction. In Untitled Jimmy Best (1980), a set of three untitled works built around a fictional African-American character, Basquiat uses code words, repetition and ‘restrained narrative’ to blur fact and fiction. As well as being esoteric and half-told, the words in Untitled Jimmy Best are glaringly visual, lyrical and sonic. Such a staccato of words gave Basquiat the power to orchestrate a new visual language with which to defy and define meaning.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled Notebook Page, 1980?-1981. Ink marker on ruled notebook paper, 9 5/8 x 7 5/8 in. (24.5 x 19.4 cm). Collection of Larry Warsh. Copyright © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, all rights reserved. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum

Basquiat died in 1988, young, rich and famous, of a heroin overdose. His tragic death alone has made the artist and his works even more desirable. Above all, Basquiat was an anomaly: he had gone from being a homeless Haitian-American street artist to a young prodigy, furiously scrawling his iconic words (SAMO, for instance) and images across walls, paper, people and even on himself. His works are still raw and brutally honest: they turn ordinary people into unsung heroes as in Tuxedo, Untitled (1982-83) and Famous Negro Athletes (1981). We constantly see black heroes, in the sketch for Famous Negro Athletes and the epic Untitled Crown (1982) for instance, reappearing throughout Basquiat’s notebooks and in his larger works.

Peering at Basquiat’s notebooks today can feel a little intrusive and unsettling. However, it also helps us understand the minutiae of how he would go on to draw and write the beauty and horrors of the world within and around him. In Untitled, he does this on a much larger scale: drawing, words and painting merge to form a life-size collage, thereby re-writing language to deconstruct the origins of time and place.

Basquiat stands out as an unrivalled artist of his time, primarily because he could juxtapose his inner world and the outer world, abstraction and figuration, ancient history and current affairs as well as the influence of African masking traditions and Post-modernism. He created a new subversive language that gave the fight against racism, inequality and capitalism in North America a human face: one that seems just as relevant today. Basquiat obliterated and then re-wrote the history of time and place with his amalgam of Neo-expressionism.

The fact that disjointed words scrawled in a notebook can morph into a stoic act of defiance, sets Basquiat apart, even by today’s terse standards on art and commerce.

Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks, April 3 – August 23, 2015, Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Mebrak Tareke is a writer, editor, curator and an independent media & communication professional. She has written for: Under The Influence magazine, Kilimanjaro and Another Africa on art, politics and culture. Mebrak, is also co-founder of TURF, a curatorial project that explores the arbitrary notion of Africana in the digital age.

More Editorial