Art between the dimensions

The Gallery of African Art in London (GAFRA) is showing “Global African Profiles”, an exhibition by Angolan artist Daniela Ribeiro and her Nigerian counterpart Ndidi Emefiele. With Oris Aigbokhaevbolo, a participant of C&’s critical writing workshop that took place in Lagos last year, they discussed living between continents and how their works relate to each …

The Gallery of African Art in London (GAFRA) is showing “Global African Profiles”, an exhibition by Angolan artist Daniela Ribeiro and her Nigerian counterpart Ndidi Emefiele. With Oris Aigbokhaevbolo, a participant of C&’s critical writing workshop that took place in Lagos last year, they discussed living between continents and how their works relate to each other.

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo: How do you see your work connected, in what ways do you find the GAFRA pairing apt?

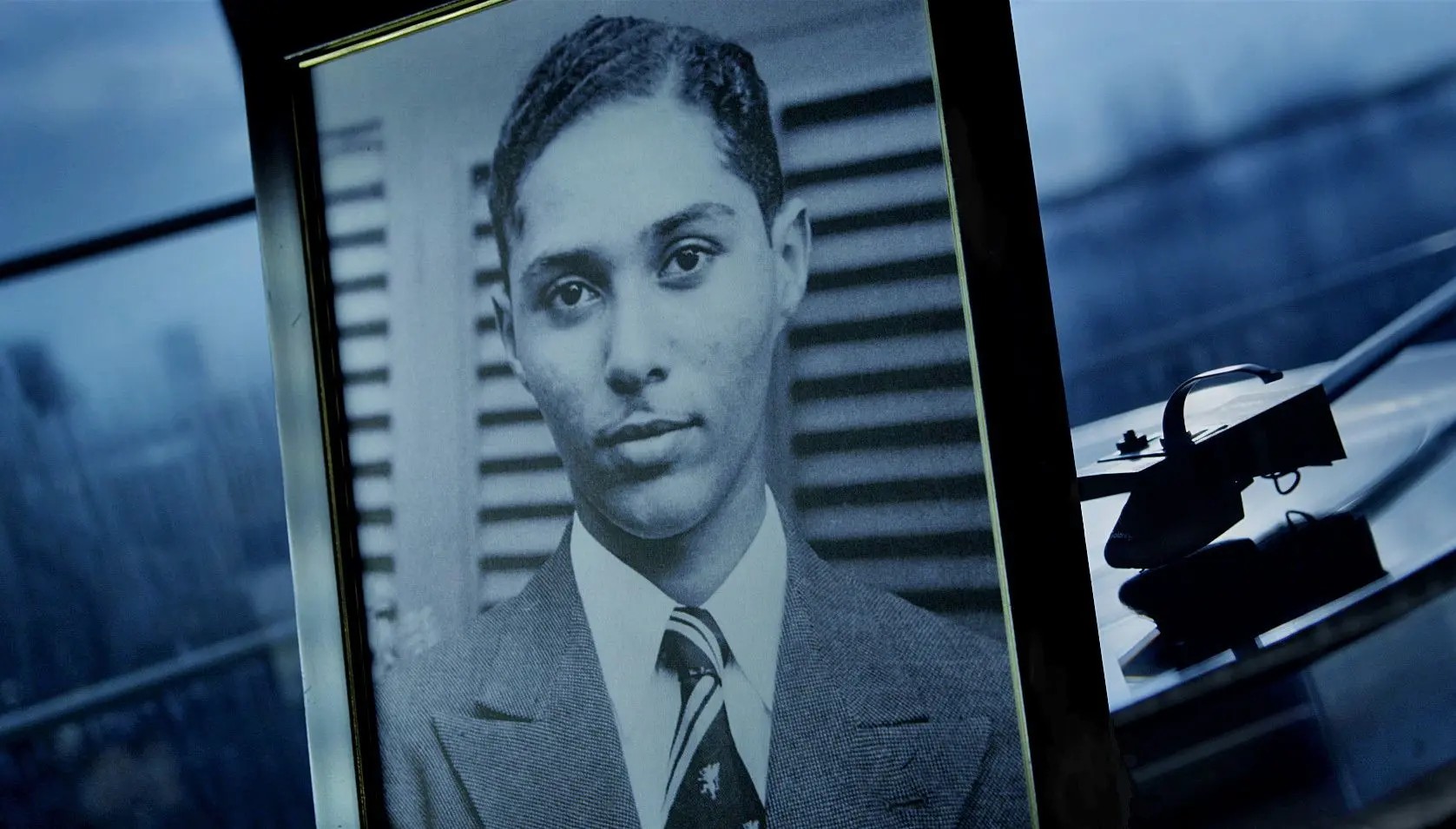

Ndidi Emefiele: My work raises questions on how culture, tradition, family, and gender form the identity of a person. I’m using the female body to represent roles of the male through clothing, gestures, and other bodily features. I thereby try to deconstruct fixed notions of identity that are prevalent in the northern part of Nigeria where I was raised. This has kindled my interest in items closely associated with the body and that's where collaging comes into the process of making, as I use them to find solutions. I see a relationship with Daniela's works in how she uses collages, although quite differently. In her work there is also a focus on identity, but on transformation by external components like technology; the question of how culture responds to technology is essential.

OA:Daniela, your work has elements resembling the future imagined by science fiction. Could you comment on the pop culture influences in your images?

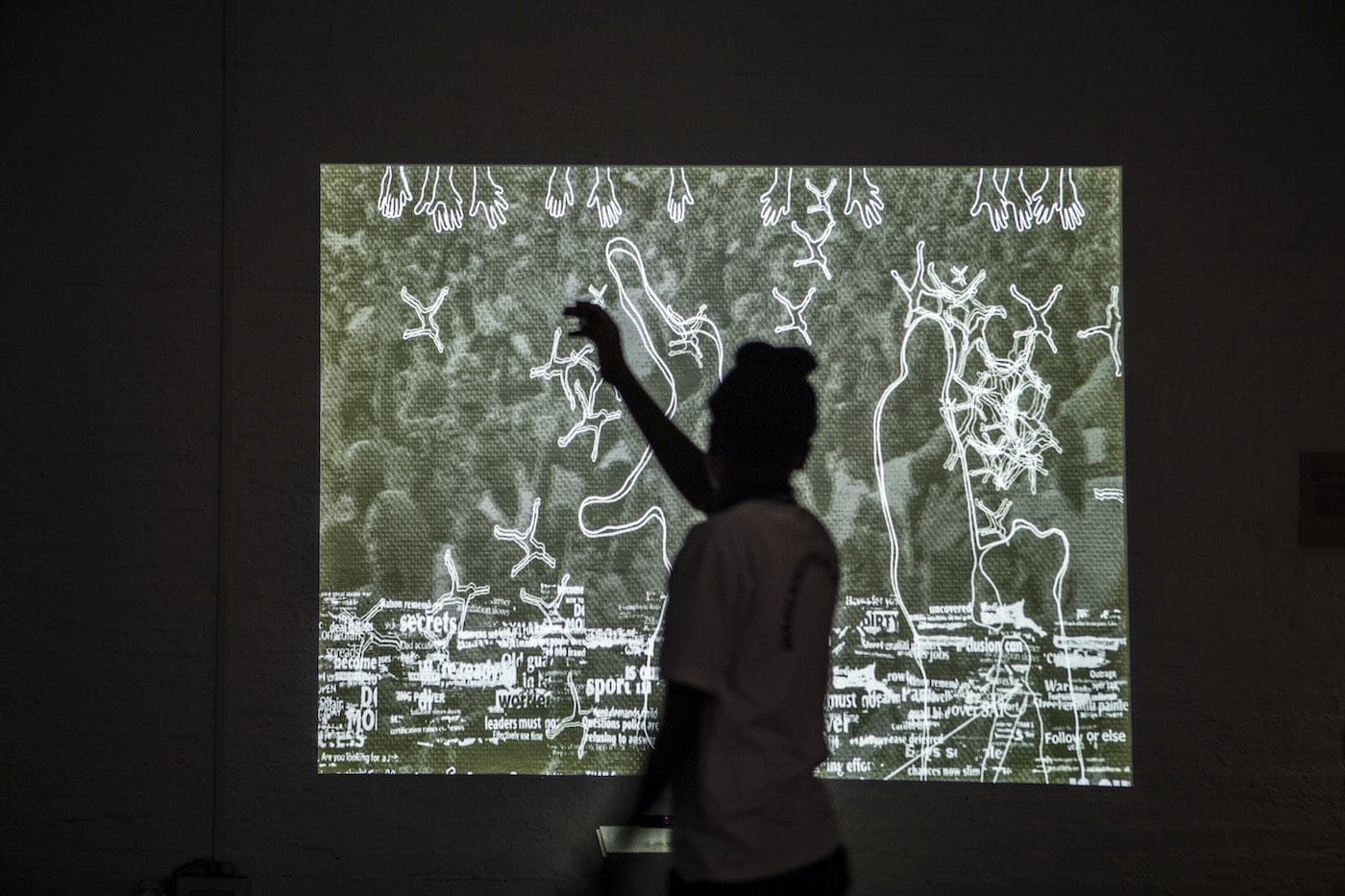

Daniela Ribeiro: My characters seem to come from a supernatural future, incarnating the stigmas of technology but with the additional strand that binds them to the natural world and humanity itself. They also contain science fictional elements, historical fiction, fantasy, and magical realism with cosmologies. At a first glance, they appear to have elements of the pop imaginary framework, but it is far from my intention to be associated with that. My work is based on science, not science fiction.

.

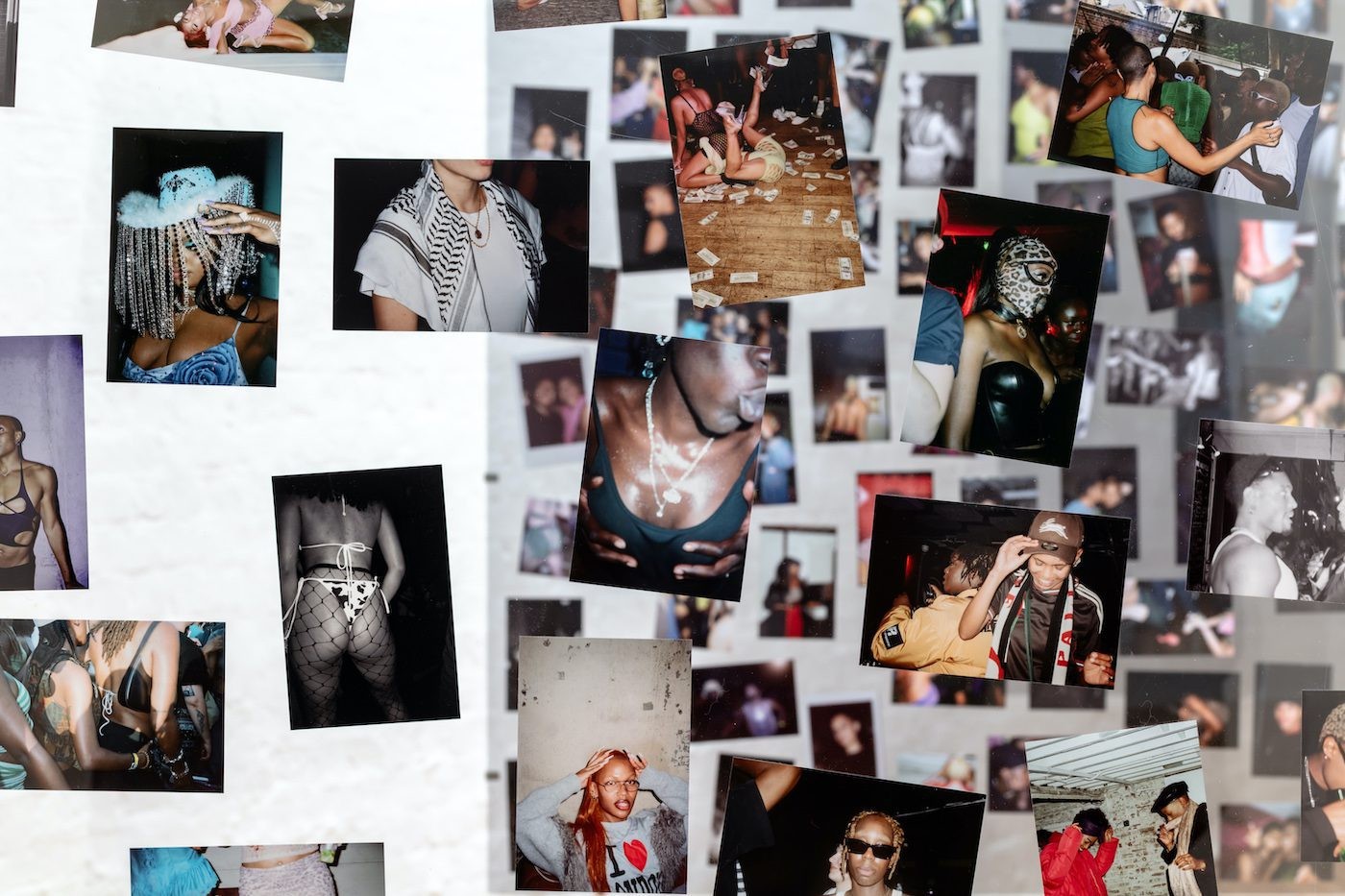

<figcaption> Daniela Ribeiro, Social Soul. Photo, resins, video, 2015. Courtesy of GAFRA

.

OA: And Ndidi, you have said that fashion is one of your influences. Could you elaborate on that?

NE: There's an incredible amount of inspiration always lurking around if one’s eyes are open to see them as viable material. I have always been attracted to things that give pleasure to touch or appeal to my eyes, hence the need to incorporate them into my work. There's also the emotional attachment to that space of creativity. At the time I was creating work in my bedroom and I literally began to look at every item lying around as a potential tool. It is related to making do with what is in the immediate environment, which gradually leads to using other elements, to other ideas and encounters.

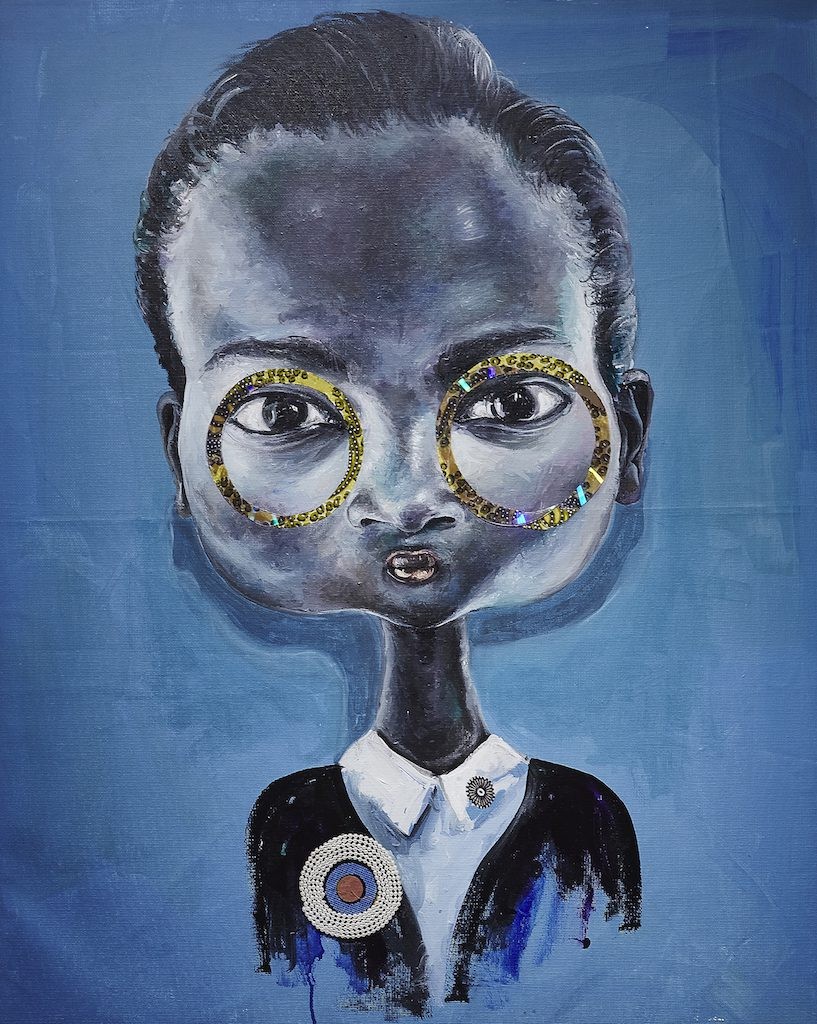

OA: A lot of your work is about the face.

NE: Yes, because you cannot tell what a person is experiencing until you look at their face. It is where communication is likely to begin. I enjoy making forms where the gaze is able to pierce the viewer and cause them to stop and pay attention, even though I try not to give out too much information. I want the observer to be able to get something out of their own interaction with the work.

.

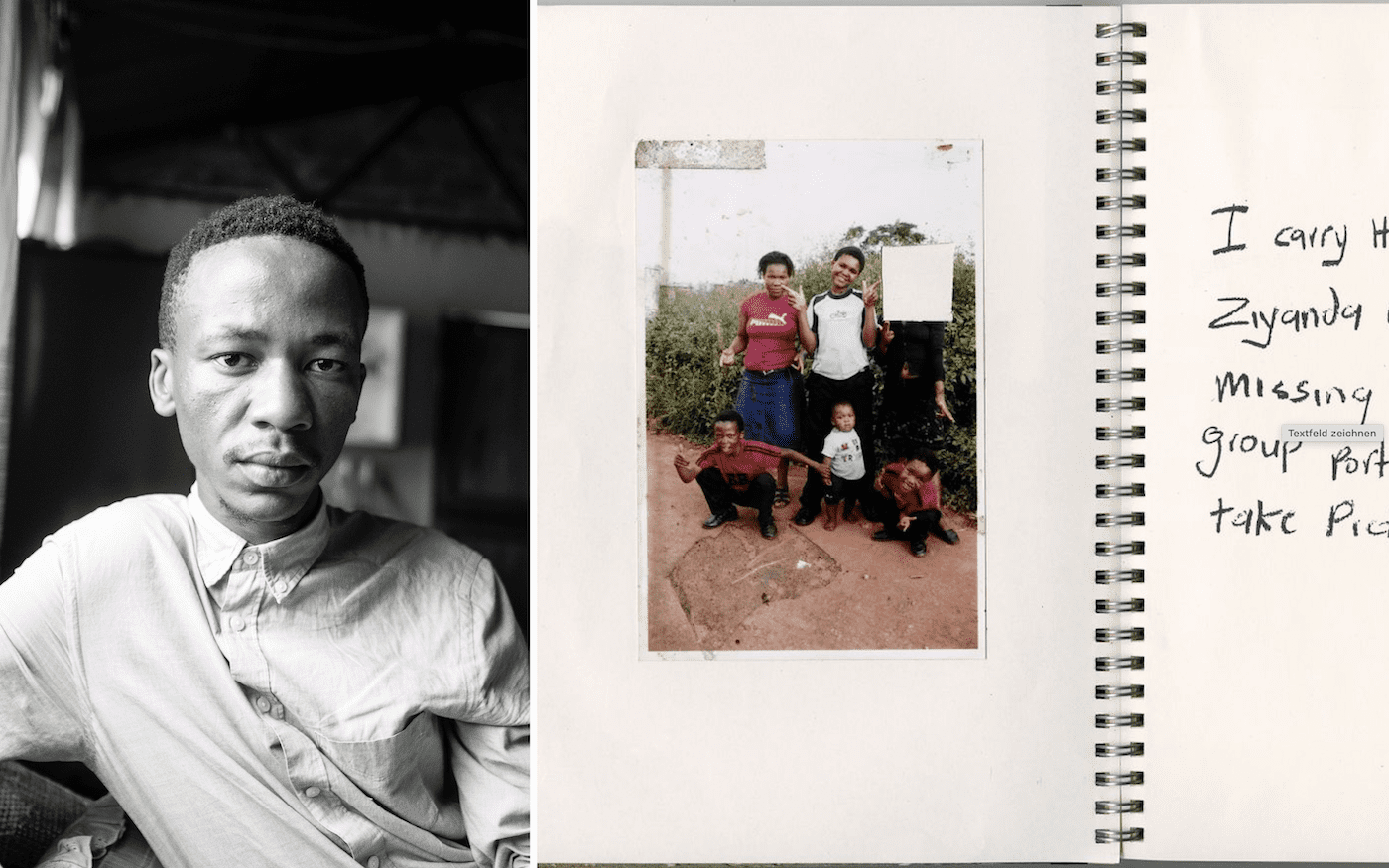

<figcaption> Ndidi Emefiele, Untitled I. Mixed media on canvas, 2015. Courtesy of GAFRA

.

DR: I can relate to that. My intention is to draw attention to a serious civilizational error where man is creating a world of rational artificial intelligence and forgetting about humanism. There is no evolutionary intelligence without genuine emotion. Destroying humanism is destroying intelligence, whichever form that intelligence may take.

OA: Both your work does not fit with the conventional notions of Africa, that vast continent taken for a country and sometimes even for a city. Is your flight from the African pop motif a conscious one?

NE: It amazes me how anyone would intentionally or unintentionally take a continent that comprises 54 countries for a single one, especially when each one of them has a name. I didn't set out to make work that did or did not ‘look like Africa’. My experience of living in Nigeria is reflected in different aspects of my work, from places visited to books read and other encounters. As well as foreign influences as I continue to experience different cultures.

DR: In general, African art is centred on the difficult task of recovering tangible tracts of a complex history and an obliterated past. The continent’s energy is still consumed by the search for its history, including legacy, memory, archive, and identity. My work, on the contrary, is a preliminary vision of a future, but a future set in a much wider context on a global scale.

.

<figcaption> Ndidi Emefiele, Rainbow Brigades 9. Mixed media on canvas, 2016. Courtesy of GAFRA

.

OA: In what ways has living between Europe and Africa informed your work?

DR: My work is all about the principle of existential duality. Living between two spaces, different time frames, multiple perceptions. I travel from dimension to dimension and it all happens at light speed. Yet, home means everything to me. The West in general has lost what for me is essential. It is dehumanisation, not poverty that saddens me the most. My home country provides me with what feeds my imagination and creativity: humanism.

NE: Going to different art schools on two different continents was interesting, but the experiences overlapped. My undergraduate programme in Nigeria was focused mainly on making work and just on some written theoretical courses. Having cultivated the habit of consistently making work in the studio prepared me for the Slade School of Art in London, which is very studio intensive and also encourages engagement in conversation, critique, research, and other art programmes that enrich one’s practice. London also boasts a large number of galleries, museums, and arts centres — where I'm able to discover and encounter amazing work. Some of which I had encountered in art history books before coming here.

Oris Aigbokhaevbolo is a Nigerian writer and culture critic. His writing has received the All Africa Music Awards prize for Entertainment Journalism.

Identity

Kombo Chapfika and Uzoma Orji: What Else Can Technology Be?

In Conversation with Lubaina Himid: The Artist Set to Represent the UK at Venice Biennale 2026

, so I dream: An Ode to Stuart Hall

London

Bernice Mulenga’s LMK WHEN U REACH

Lindokuhle Sobekwa Wins the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2025