Jean David Nkot’s work examines the human condition and its place in a dehumanizing period. Here the artist tells Dagara Dakin more about the two works he exhibited at the SUD triennial

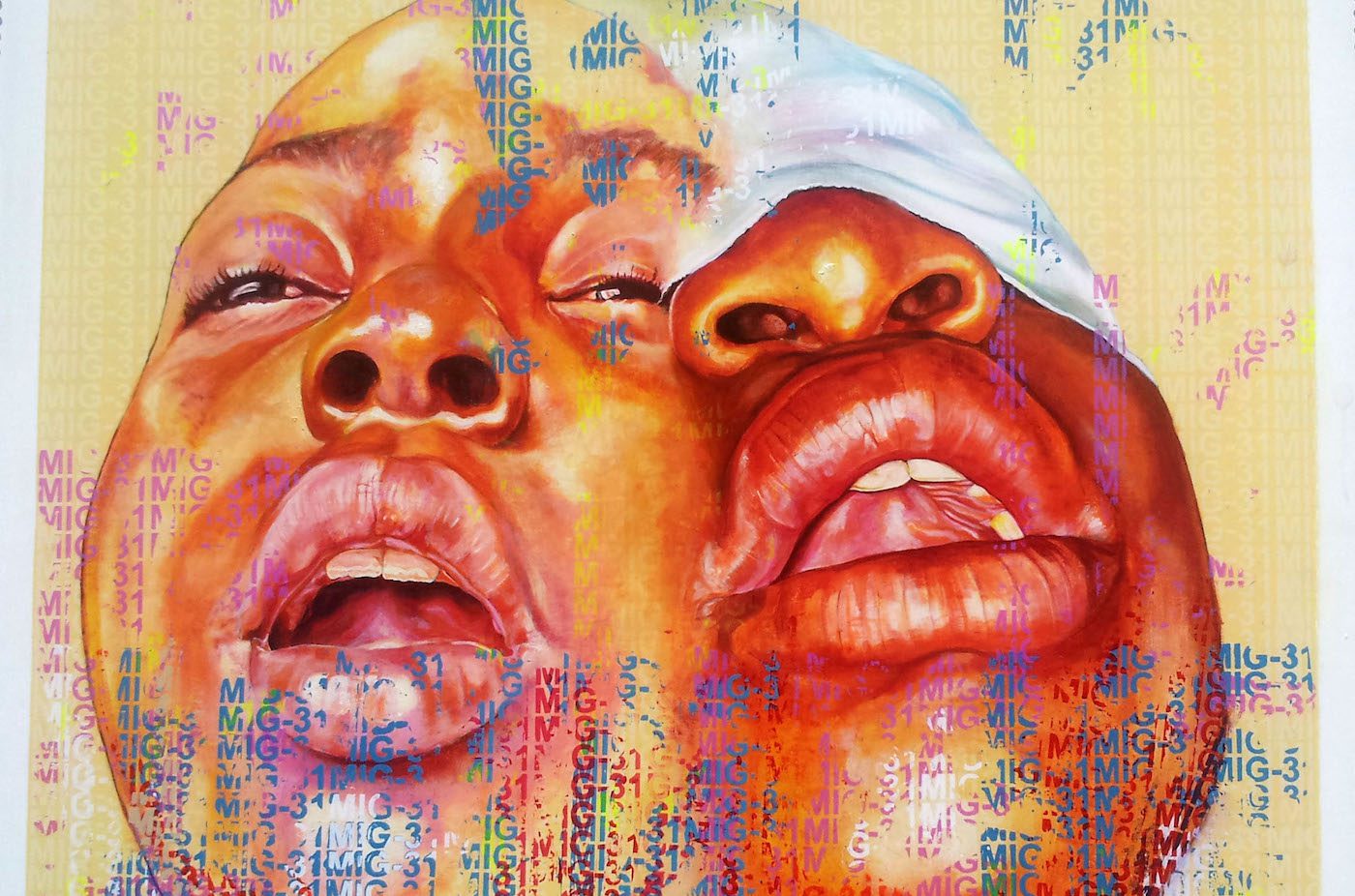

Jean David Nkot , www.kolofata.it (Detail), 120x120cm, mixed media, 2015. Courtesy the artist

Dagara Dakin: What would you say is the inspiration behind your artistic calling?

Jean David Nkot: As the saying goes, we don’t choose art; art chooses us. Things happened quite naturally and it was out of pure passion that I embraced this work. It has been a great help in my life, which wasn’t at all easy when I was a child. Practicing art gives me a sense of freedom, pleasure, and above all spiritual wealth. I think that my artistic calling is the result of various frustrations in the family — namely, the absence of expression, violence, and a lack of understanding. All of which pushed me toward this work, which allowed me to exteriorize things I had in my heart. There have also been encounters with other artists who had more or less the same preoccupations.

DD: Was this the first time you have participated in the SUD triennial? How is this event different from the other biennales taking place on the continent that you’ve been involved in?

JDN: I would say it was my first official participation. Aside from this, I exhibited work during the third edition of SUD on the theme of metamorphosis, but this was in the Off program together with the artist Salifou Lindou, with whom I had done an academic internship as part of my bachelor’s in visual arts, specializing in drawing and painting. But this year was the first time I’m featuring in the official selection. I submitted a project to the jury, who found it interesting. I’ve been a professional artist for four years but I’ve been part of this milieu for seventeen years now, and this was the first time I’ve been selected for an event of this size. I had the opportunity to take part in some discussions, some exchanges with a number of other artists who’d been selected. I also attended the conferences that were organized during the preparation phase for this triennial, and before that I took part in the Dakar Biennale, although this was still in the context of the OFF program.

DD: Which project did you present at the SUD triennial last year?

JDN: I showed a public work that I’ve called Les Dits Et Les Non-Dits, which was divided into two parts. The first part was a spatial installation of a false façade realized on metal and measuring 8.5 by 2 meters. It symbolized a place of remembrance that is none other than the family house of the nationalist Ruben Um Nyobé, an important figure in Cameroon’s struggle for independence. There is often a lack of awareness today about the history and actions carried out during this period. This façade showed the speech Um Nyobé gave to the UN on December 17, 1952. The distinctive feature of this work is the highlighting of fragments of this address, which speaks of the human dimension, the theme of the triennial. The second part, in turn, was a newspaper that I have titled Les Archives Du Cameroun, inspired by Alain Foka’s program Les Archives d’Afrique, which deals with the contemporary history of Africa through its great men. The difference is that Foka’s archives are audio, while mine are written. It was a way for me to tackle the issue of archives in my country and their accessibility. One of the questions I asked myself was whether it might not be necessary, and useful, to have a newspaper dedicated to the memory of Cameroon, which points up its history via its great people. I think there are so many things we don’t know about our country and there’s too little clarity about the history of the period prior to independence. In my opinion, this could be one way of paying homage to these people who have made our country what it is.

All in all, it was a project that invited us to reflect on the need to rehabilitate the memory of people, the places of memory.

DD: Before you participated in the triennial, was the question of human rights an integral part of your thinking or your artistic approach?

JDN: Yes, because my work on the question of violence and its normality in our age pushes me to examine the human condition and man’s place in a dehumanizing period, where people are only regarded as important when they are synonymous with financial gain, and where capital matters more than social issues. My whole artistic approach is concerned with the human condition and the place that it occupies today. I want to condemn modern-day rivalries and controversies, be they political, religious, or cultural in origin. I would like to foster a fundamental awareness of these kinds of dehumanizing practices and encourage people to break free of them.

Dagara Dakin is a freelance writer and curator based in Paris.

Translated from French by Simon Cowper.

This Interview was first published in our latest Print Issue #8. Read the full magazin here.

More Editorial