Aiming for the Stars

Zambian artist Stary Mwaba is currently showing work at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. Titled Life on Mars, his solo exhibition of paintings and sculptural installations explores aspects of Zambia’s recent history, including a 1960s space mission conceived in the optimistic aftermath of independence and the country’s more recent experience of Chinese business interest in the …

Zambian artist Stary Mwaba is currently showing work at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. TitledLife on Mars, his solo exhibition of paintings and sculptural installations explores aspects of Zambia’s recent history, including a 1960s space mission conceived in the optimistic aftermath of independence and the country’s more recent experience of Chinese business interest in the copper-rich country. Mwaba, who lives and works in Lusaka but is currently a fellow of the KfW Stiftung in Frankfurt, speaks to our author Magnus Rosengarten about his new exhibition.

Magnus Rosengarten: You move a lot between the realms of imagination and reality in your creative process. How does it enhance your creative process?

Stary Mwaba: I totally agree, I am always moving back and forth. At the moment I am very interested in dealing with archival materials. I am coming from a background where most of the history has been orally translated to the next generation. I think there are a lot of gaps, and I fill in the gaps with imagination.

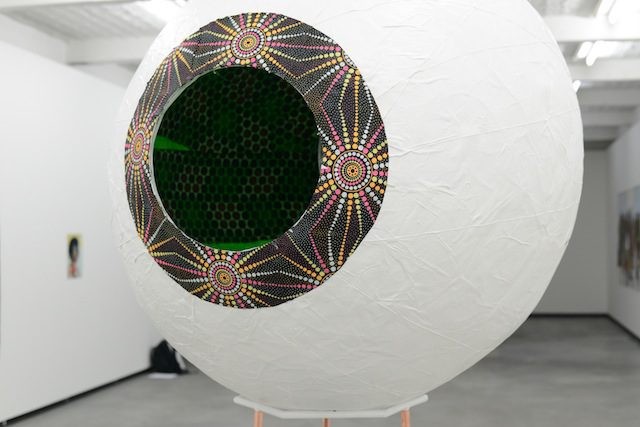

Stary Mwaba, Installation view of D-KALO 1, 2015. Courtesy of the artist

MR: Your exhibition Life on Mars includes a sculpture titled “D-KALO 1”. It is named after the spacecraft developed by the late Zambian science teacher Edward Makuka Nkoloso who in 1964 founded the National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy, an unofficial space academy . He wanted to send a spaceship to Mars. Is your work informed by the concept of Afrofuturism?

SM: Yes. During the period of Zambian independence (1964), there was this connection between freedom, independence and space. When you look at the recent history of Zambia, our mines literally collapsed a decade after independence and the economy went down. [Between 1974 and 1994, per capita income declined by 50%, leaving Zambia the 25th poorest country in the world.] We had to look back into history when people were so enthusiastic, very positive about the future. And Nkoloso is one of those people who had this huge dream of going into space. If you look into the man’s life you understand the enthusiasm that characterised the period of independence.

MR: You went into archives for this project as well. How does “documented history” play out in your creative process?

SM: A lot. When I went to the National Archive in Zambia there was very limited information about Nkoloso. At some point he became more of an intelligence figure and was very close to President Kenneth Kaunda. He also sat on the board of African National Congress, South Africa’s current ruling party who were then still banned and operating in exile from Lusaka. I found a lot of pictures and also got a very short video. It shows Nkoloso training. He talks about where he is planning to launch his spaceship. It also shows Martha Mwamba, the girl who Nkoloso was planning to send into space for the first time.

MR: A woman going into space in the 1960s?

SM: Amongst the group of cadets at Nkoloso’s Zambia Space Academy was a 17-year old girl named Matha Mwambwa. I think it is really interesting because there are things you really need to understand. There are a lot of issues around gender inequality now. I think back then women had a more prominent position.

MR: A more contextual question. Who is your work addressed to?

SM: I come from a background where I do a lot of social work. The story around Nkoloso sounds like a fiction, for example. And I did a small workshop where I showed a video to young girls. In that group we started imagining what Mars is like? “Let’s create Mars!” That’s a different audience and I make work with them. And I think being here in Germany, the work really addresses the ongoing misconception of the African continent and its people. It is also for me to talk about my inspiration. This was a race: USSR and the US were both competing to go into space. It was a big thing and we were in the race too. It really talks about my inspiration, as an African, as a Zambian, and as an artist.

MR: What does the current presence of China in Zambia mean to you?

SM: Two things: On the one hand China is offering options to Africa. We did not have so many options before. Our economy is growing because China is there. There is so much talk about economic colonization, but I think that was in place already. China is not the one introducing it; China is simply coming to Africa for the same reason Europeans came. On the other hand, I am not sure if you can trust them. They are grabbing a lot of land. They treat workers badly. My work is about asking long-term questions. Are we going to be ripped-off, like always, or are we going to benefit? But I think it is really up to us, Zambians, to choose which direction to go.

Stary Mwaba. Courtesy of the artist

MR: Your exhibition includes a series entitled “Chinese Cabbage”. What does cabbage symbolize to you?

SM: I never really knew the vegetable growing up. We ate other vegetables. But it is there now and it has changed the vegetable landscape. In a lot of places, you only need to say, “I want Chinese,” and it is understood that you want cabbage. You have this vegetable, which is good for you, but it is also a foreign plant – it probably introduces certain pests. It really is a material that reflects what is happening in Zambia. My work is framed around a simple primary school experiment to do with how plants absorb minerals and water? The cabbage works really well. It is unbelievable how it absorbs the different food colours I put it into the water. For me the “Chinese Cabbage” series represents the Chinese presence in Zambia and many parts of Africa, their absorption of the minerals.

MR: How has your residency in Berlin affected your practice?

SM: It has been an amazing time to see a lot of art around from everywhere, but also the African artists in the diaspora, just seeing what their work represents. There is a model, you have this system, somehow you have to fit in according to the demand, what you are expected to say. It also helped me to think about what I do, and why I think my work is important.

MR: Why is your work important?

SM: For so many reasons, even if I struggle sometimes with the issue of audiences. My work is sometimes displayed not as art but more as an educational tool. I am really happy I can educate viewers, but it is good to withdraw it and place the work in a space where a completely different audience sees it. It shifts the message in a way.

Stary Mwaba, Life on Mars, March 6 - March 29, 2015, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin.

Magnus Rosengartenis a filmmaker, journalist and writer from Germany. He lives in New York City and currently works towards his M.A. in Performance Studies at NYU.

Feature

We're Still Here: Thero Makepe’s Visual Jazz

C& Highlights of 2025

Maktaba Room: Annotations on Art, Design, and Diasporic Knowledge

Afrofuturism

‘Apprendre à Flamboyer’: Collective Joy in Practice at Palais de Tokyo

C& Magazine’s Highlights of 2023 You Might Want to Read Again