A non-linear history of Dak'Art

Taken from the C& Print issue No.1 – Here The first Dakar Biennale is generally thought to have been held in 1992. Less remembered is the festival that brought together artists from around the world in 1990. It seems that the event held that year and dedicated to literature has been completely forgotten. …

Taken from the C& Print issue No.1 - Here

The first Dakar Biennale is generally thought to have been held in 1992. Less remembered is the festival that brought together artists from around the world in 1990. It seems that the event held that year and dedicated to literature has been completely forgotten. The 1990 festival was the debut of the Biennale of Arts and Letters, which was originally planned to alternate every two years with a festival devoted to visual art. Senegalese artists and intellectuals had called for an event that would promote their creative output and publicize their work on a large scale. Changes to the theme muddled the question of when exactly Dak'Art was born. The tenth anniversary of the event was celebrated in 2002, revising the timeline to exclude the 1990 gathering.

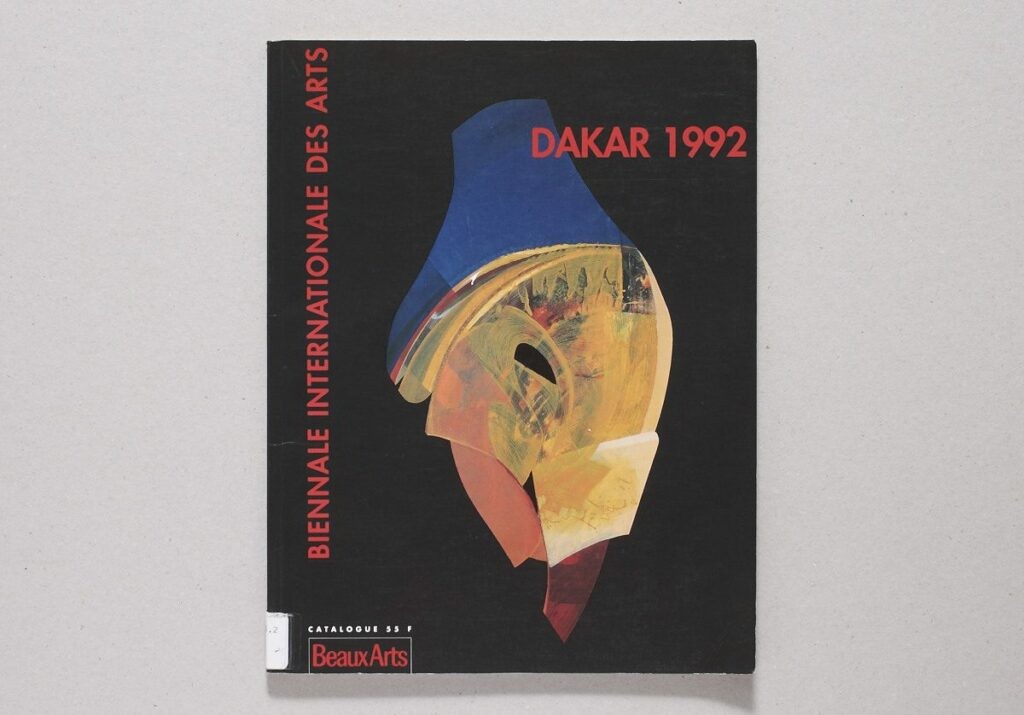

<figcaption> Courtesy: Stuart Hall Library at INIVA

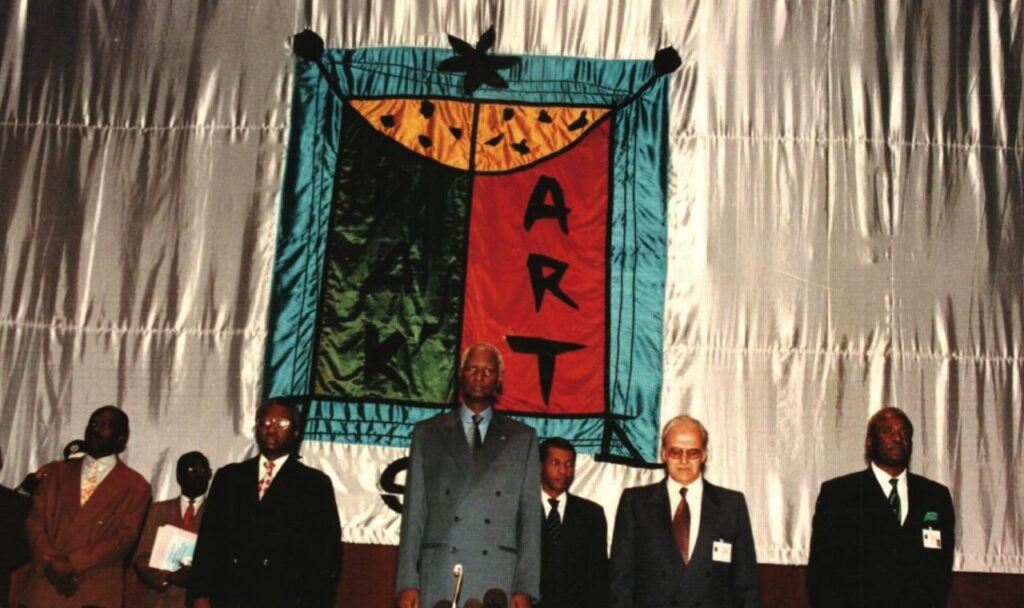

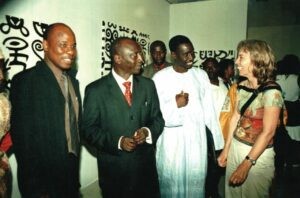

The second Dak'Art in 1996 repositioned itself as the „Biennale of Contemporary African Art“, a change which would have a decisive impact on the future of the series. This was a kind of rebirth in a sense, but it was also a crucial step that distinguished the event within the increasingly crowded competitive landscape of biennales. The new trend across Africa towards large events demanded an appropriate new organization that could weather out a period of trial and error. From then on, the current model completely remade the event into a creative platform, both for the artists who were selected and for the young curators chosen to take charge of artistic direction.

<figcaption> Opening Ceremony of Dak’Art 1996, Daniel Sorano Theatre Dakar 1996. President Abdou Diouf is standing in the middle, courtesy of Dak’Art Biennale Secretariat

<figcaption> Courtesy: Stuart Hall Library at INIVA

A biennale's sense of its history is characterized by a strange trio of forces: continuity, amnesia and disruption. In Dakar, frequent references to the first World Festival of Black Arts (1966), which has been invoked from the start, introduce another variable to the mix. This is a convenient way to claim continuity with a prestigious cultural event from the past and to situate the modern exhibition within a purely African genealogical context. Be that as it may, it would be overly simplistic to draw a straight line from the 1966 Festival to Dak'Art, given the differences in the two events' mission statements, challenges and structures.

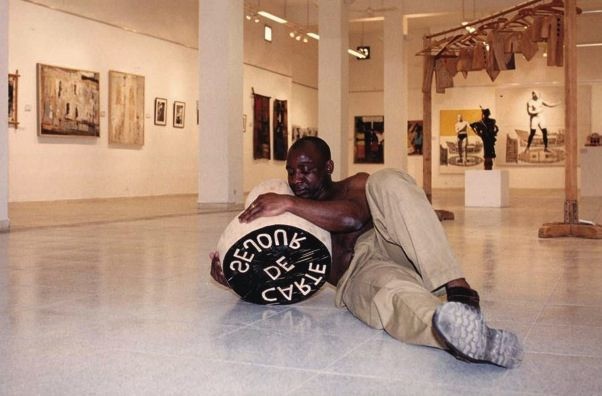

<figcaption> Courtesy: Stuart Hall Library at INIVA

As contrived as this claim of kinship may be, it at least allows Dak'Art to reflect on itself within a narrative rooted outside of the Venice Biennale, which scholarship on the subject takes to be the basis for all biennales. A more disjointed and less linear storyline, yet to be written, would call attention to exhibitions that were forgotten or never made it past the planning phase. Of the various planned biennales that were forgotten, but whose challenges Dak'Art still faces today, let us consider one that was presented in the pages of the journal ICA Information in 1977. Records of the event are limited to that article, but what we do know bears a striking resemblance to the Dakar Biennale, a comparison that is rather telling for the history of that exhibition. In 1976, the executive council of the ICA (Institut Culturel Africain, or African Cultural Institute), based in Dakar, expressed interest in organizing a biennale dedicated primarily to fine art and rotating among member states. This exhibition would lend vigor, effectiveness and impact to the institute's program, which, when it came to art, was mostly limited to organizing a competition to award each year's Grand Prix ICA. The journal article describes a project whose agenda of planned undertakings was clearly ahead of its time. The organizers had meticulously identified the challenges facing such an exhibition. These included the need to promote an interchange of artists and artwork, to foster meetings among artists, and to publish catalogues – but above all, the project approached the biennale from a long-term view, advocating the establishment of modern art museums in order to stimulate a market for existing museums to purchase artists' work. These last points are particularly important, as they highlight a structural problem still encountered at Dak'Art.

<figcaption> Dak’Art 2006’s official exhibition opening, courtesy of Dak’Art Biennale Secretariat

<figcaption> Courtesy: Stuart Hall Library at INIVA

The city of Dakar completely lacks a contemporary art center where exhibits can be organized on a regular basis. Such a space would enable artists to broaden their horizons much more than a biennale could on its own and would also help train local curators. These museums could then take responsibility for organizing the exhibition on a professional basis. Neither did the ICA Biennale's organizers neglect non-artistic questions such as tourism and education. The biennale was thus intended as an ambitious tool for developing the art scene in ICA member states. It aimed to launch a pan-African association of fine art, which would explore the status of the African artist and develop national associations to network fine artists in participating countries. That way the selection of artists could steer clear of political influence on the part of the respective countries, a lesson the organizers seem to have learned from prior experience. Last but hardly least among their requirements, the organizers worried whether they could realize international quality standards for the gathering. This project was in the same vein as the noteworthy „Incubator for a Pan-African Roaming Biennial“, initiated during the Manifesta 8 European Biennale (2010), which invites curators to contemplate how the model of the roaming biennale could be adapted to Africa.

<figcaption> Courtesy: Stuart Hall Library at INIVA

Although the ICA's Biennale bore the recognizable influence of Léopold Senghor, the project's initiators wanted to distinguish themselves from the World Festival of Black Arts by specializing in visual art. The ICA Biennale may only have survived as the prestigious big brother of its modern derivative and stand-in, but it also offers a foretaste of the future emergence of Dak'Art. In 2016, there will doubtless be another round of references to the legendary 1966 festival, thereby neglecting less prominent projects (some that never actually materialized, but channeled energies nonetheless). These could and should be remembered alongside those two major events of the Senegal cultural scene.

<figcaption> A section of Dak’Art 2012 with guests milling around the performance piece by South African artist Lerato Shadi © Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi

Cédric Vincent is an anthropologist, postdoctoral fellow at Centre Anthropologie de l'écriture (EHESS-Paris), where he co-curates the "Archive of Pan-African Festivals" program supported by the Fondation de France.

Senegal

Still a Powerful Platform for Critical Dialogue around Art, Ecology, and History

OFF Biennale Dakar 2024

60th Venice Biennale: National Pavilions of Benin, South Africa, Senegal and Ethiopia

Exhibition Histories

documenta 11

Tendances et Confrontations