Ensuring that we see ourselves

Our author Magnus Rosengarten talks to California-based artist EJ Hill about Trump, activism and the restorative potential of using the body in art

Renowned artists who have lived in the US for decades told us they are seriously considering not returning to the US as long as Donald Trump is in power. An influential curator from New York emailed us the day of the election, still completely in shock: “Winter in America. It’s certainly tough here. But folks feel ready to fight!“ We have received many similar statements by artists, curators, academics, writers – emotional, powerful, concerned reactions to the current status quo. In the new series “Don’t Mourn, Organize!” our question to them during the next couple of weeks and months will be: How can we form a creative perspective, how do we react by not solely concentrating on the uncertainties and crises but instead transforming ideas into platforms and strategies for change?

.

C&: James Hetfield, the front man of Metallica, recently said in an interview that the vote for Trump would not change anything about his work because he did not want to give this new government the power to influence his artistic work. What is your perspective on this in terms of your art? Will the vote impact your work?

EJ Hill: This vote will most definitely impact my work, but I am not sure to what degree. David Hammons once said that he doesn’t really like art at all, that he is more concerned with symbols, and art is just one context for engaging with, or challenging, the power of symbols. This election isn't about one man or his administration. This is about everything he and his supporters symbolize, what they represent. And let's be honest, what they represent is as old as America itself. So will the results of this election impact my work? Yes, undoubtedly, but I imagine the impact to be similar to that of November 7, 2016. Or like, any other Monday prior.

C&: What is your perspective on America's current condition, your perspective as a citizen, as an artist? After all, is it really that new and unprecedented?

EH: Exactly, no, none of this is new at all! And I think that's what's been the most frustrating part about all of this for me. The fact is that a lot of us – Black people specifically – have been living within this reality for a very long time, and fighting against it for just as long, but now that so-called left-leaning white people feel threatened, there seems to be a particular kind of urgency, a certain trend toward action. And it's difficult sometimes not to view this all as some bizarre tagging-out-of-the-ring, you know? Part of me is thinking, "Where the hell have you been?", but the other part of me is saying, "Okay, your turn."

.

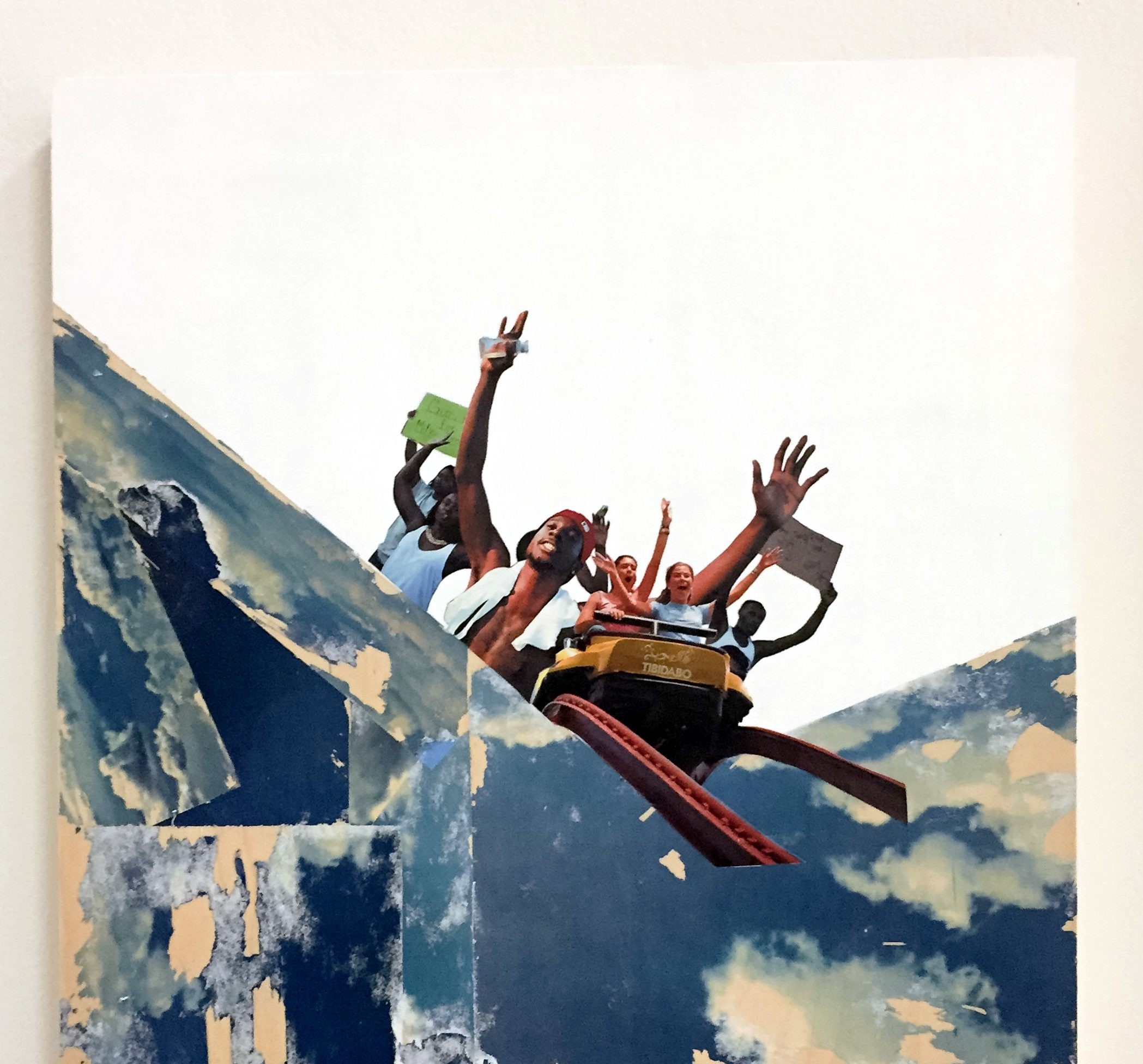

<figcaption> EJ Hill, Summit, 2017. Photo transfer and wood burning on birch panel. Courtesy of the artist and Praz-Delavallade

.

C&: As a performance artist, what role does your body play in your practice? What is your relationship to it?

EH: For me, performance is grounded in the attempt to negotiate the constant push and pull between presence and absence. And when you exist in a body that is rendered invisible by racist, heterosexist, misogynist, classist, or ableist structures, hyper-visibility becomes the paradoxical rule. It’s almost like, "You see me everywhere because you're trying so hard not to", and so, much of my performance work is in direct response to this. It's important for me to insert my body into physical or ideological spaces where I may not be warmly welcomed, to ensure that I am seen, but perhaps more importantly, to ensure that we see ourselves.

C&: Do you see any healing or curative potential in performance art or practices that involve the body as an immediate instrument? Is there potential for more immediate contact with audiences?

EH: Yes, performance is almost medicinal in that way. Any time we're dealing with our bodies, we're dealing with every scratch, bump, and pulse that it has ever experienced—we carry all of our physical and psychological echoes in our skins, our bones, everywhere we go. And if we don’t release some of that every once in a while, or transform it in some way, we might actually be a little worse off.

As far as contact with audiences goes, I don't think my presence or action in the museum or gallery or art contexts in general, is that effective or immediate, as these spaces are generally operating within the same prohibitive power structures as many other institutions in contemporary society. Action around the dinner table with family, action at the grocery store, gas station, on the sidewalk, or on the subway – where the people are – that's where the gold is. That's where the potential for presence to resonate exponentially is the highest.

.

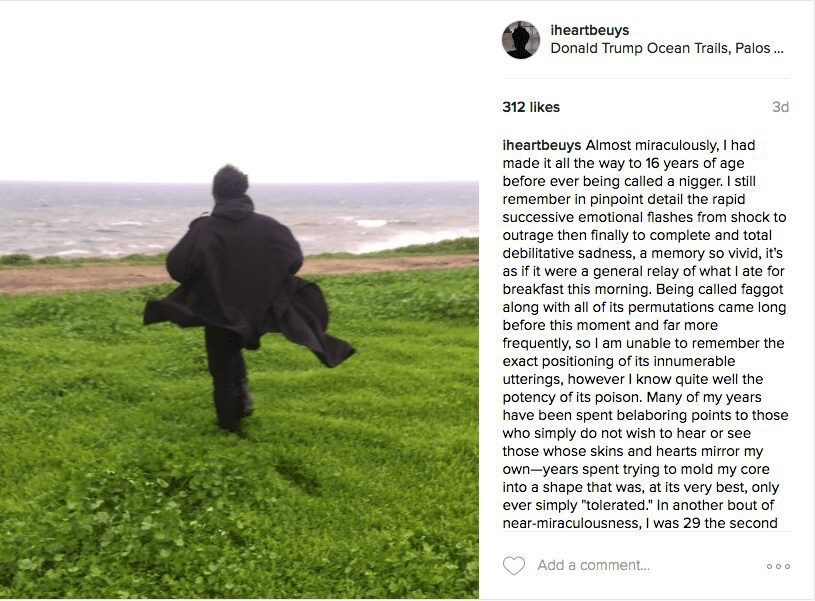

<figcaption> A screenshot from EJ Hill's Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/p/BPhMk0dga0G/. Photo by Peter Tomka

.

C&: What is sexuality to you? How does it inform your art?

EH: I could literally spend the rest of my life elaborating on this question! But following up on your previous question, sexuality might actually be the most healing and restorative space. People forget that sexuality doesn't necessarily have to include sexual acts. It's also the space of desire, attraction, fantasies, repressions, and traumas. And all that manifests in different ways. So when we share ourselves intimately, it's like a tacit request to be cared for and to hold or regard all that we bring with us as valuable. We're entrusting others to help undo what has been done to our bodies. But sometimes they further reinforce what we're trying to get away from, and that risk is all part of the healing process. It takes huge amounts of courage to continually readjust the dials on our desires, and to tweak our dosages in an attempt to find that perfect remedy, that bliss.

C&: As Toni Morrison reminded us recently, this is the time to get back to work as an artist. What will you be working on specifically in the coming months, and years, perhaps?

EH: I like to meditate on a certain mantra or theme when I'm producing a body of work. Last year, while in residence atThe Studio Museum, I had a piece of blue painter's tape on an inconspicuous part of my desk and on it I had written the words: "A monumental offering of potential energy." It eventually became the title for the work I showed in our exhibition Tenses. Now, I have a sheet of paper taped to my studio wall that reads: "The necessary reconditioning of the highly deserving." I'm not sure if it is a titular move just yet, but I'm definitely approaching new works (sculptures and paintings mostly) that nod to elevation and the imperativeness in so many of us to be able to see ourselves way, way up.

.

ejhill.info

.

Magnus Rosengarten is a filmmaker, journalist and writer from Germany. He lives in New York City and currently works towards his M.A. in Performance Studies at NYU

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

In Conversation

The Deconstructive Lens of Ngadi Smart: From Drag to Climate Change

On Ghosts and The Moving Image: Edward George’s Black Atlas