What Collective Remembrance Is For

25 October 2019

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Peggy Pirsche

4 min de lecture

Anniversaries are a chance not only to remember but to reevaluate history, writes Peggy Piesche.

Anniversaries and jubilees allow for a momentary memory, while also giving occasion for the collective mentality to be rearranged and realigned. In these moments, a renegotiation and re-legitimization of orientations and values becomes possible. The German majority society is currently undergoing an extended phase of collective remembrance. It began in 2018 with a retrospective view of fifty years post-1968.

In Germany, the years around 1968 are remembered as a time of transformation, as a young, internationally oriented awakening, shaped by the process of coming to terms with National Socialism. But what is underappreciated in the majority remembrance of 1968 are the revolutionary and emancipatory Black and People of Color (BPoC) movements which made the events possible in the first place. These include the liberation and independence movements on the African continent and the revolution in Cuba. They must be transported into the memory of 1968_for the majority, but above all for the BPoC communities themselves.

This year, the fall of the Berlin Wall will be commemorated collectively. November 9, 2019, marks thirty years since the opening of the border and the reunification of two states whose forty- year political division was symbolized by the wall. The culture of remembering this is marked by a linear narrative that is usually reduced to images of national success, but the history of the opening is in fact a complex process without a start and endpoint. It cannot be reduced to a heteronormative and nationally constructed perspective. The politics of remembrance therefore needs to be capable of more. They need to actually shift the perspective. Remembrance must not only take the majority society into consideration but also bring to the fore BPoC actors, places, events, and discourses of the time who fought for cultural, intellectual, and political self-determination. When German national issues became increasingly important after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the GDR, the already marginalized perspectives of migrant/BPoC struggles for equality, self-determination, and political participation were rendered even more invisible.

Right-wing extremism in the context of the opening of the Berlin Wall tends to be associated with developments in the so-called Neue Bundesländer (new federal states—that is, former East Germany). But even before the reunification of the two states and parts of Berlin, there were violent right-wing attacks on both sides. Then, the increasing social acceptability of discriminatory discourses as well as racist agitation and violence in the early 1990s resulted in a very tangible narrowing of public space—both on an individual level and for political migrant/BPoC movements.

In the collective memory of these movements, however, reunification also meant a new space in which projects and sociopolitical practices across communities could became possible. Even before 1989, there had been isolated contact between marginalized actors from West and East Berlin. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, a multitude of debates, actions, and networks were able to emerge. This year’s anniversary gives cause for a collective mentality to be negotiated in the present and legitimized for the future. BPoC communities must also be able to identify themselves with this memory, because remembering becomes a violent act when groups are written out and their collective identities whitewashed in order to create a societal universalism. Intersectional remembrance work is inclusive and resolutely asks for the missing pieces.

Peggy Piesche, born and raised in the GDR, is a Black German litarary and cultural scientist and transcultural trainer for critical whiteness reflection in academia, politics and society. She has been part of the Black (German) movement and a co-woman of ADEFRA e.V. (Black Women in Germany) since 1990, and an executive board member of ASWAD (Association for the Study of the Worldwide African Diaspora) since 2016. Her research and teaching focus on the fields of Diaspora and Transcoloniality, Spatiality and Coloniality of Memories as well as Black Feminist Studies and Critical Race and Whiteness Studies.

This text was initially published in the 10th C& Print Issue Another 89. Read the full magazinhere.

Plus d'articles de

Sampling the City: Tristany Mundu’s Cypher with Linha de Sintra

The Entanglement of Migration, Indigenous Peoples, and Colonialism

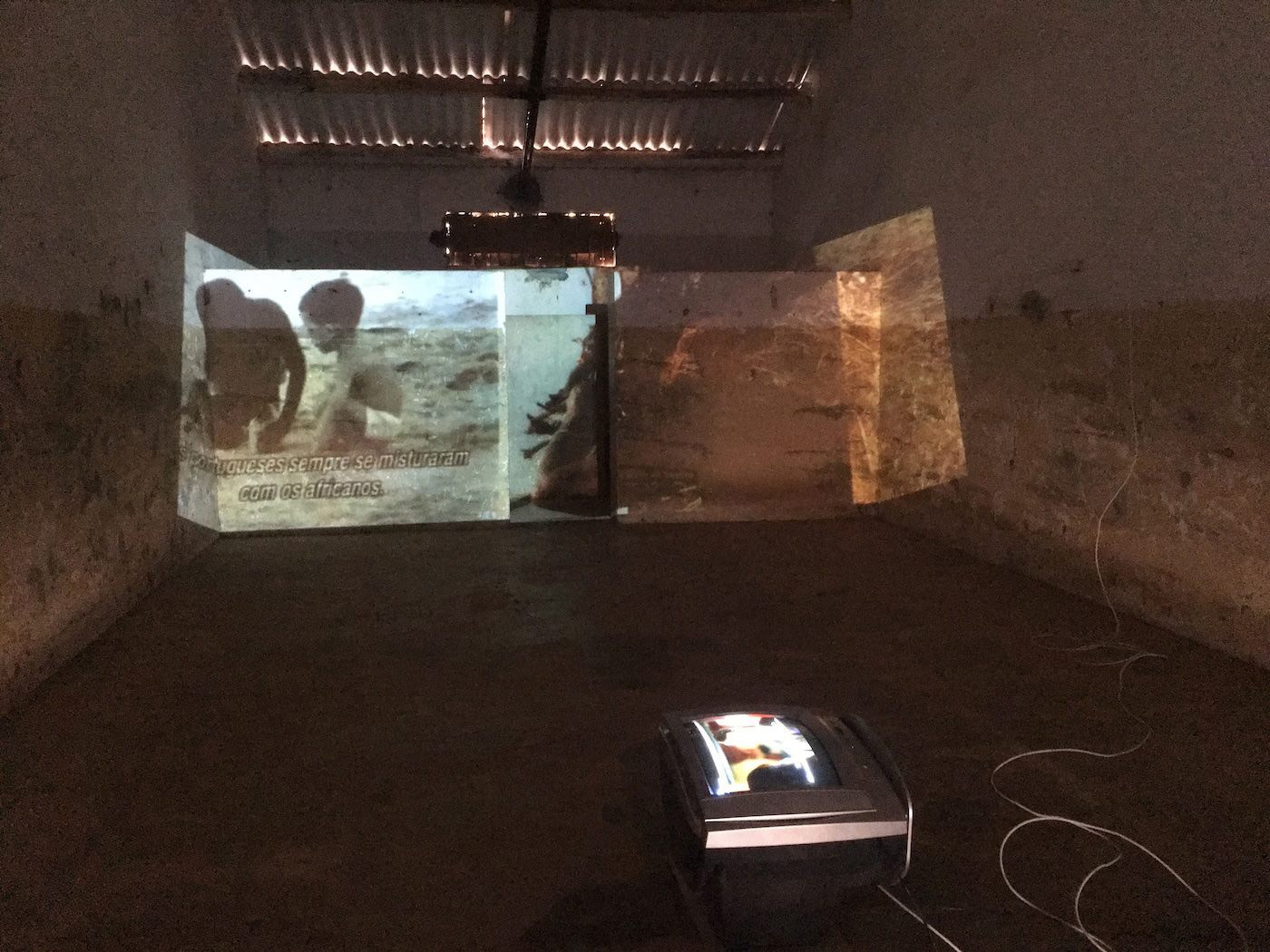

Cabo Verde’s Layered Temporalities Emerge in the Work of César Schofield Cardoso

Plus d'articles de

The Re:assemblages Symposium: How Might We Gather Differently?

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones