Honoring Ben Enwonwu at Tate Modern with the international conference “Positioning Nigerian Modernism,” facilitators Kerryn Greenberg and Bea Gassmann de Sousa and their guests discussed the vulnerabilities of established theories, politics and coloniality, as well as the disappearance and sudden resurfacing of certain paintings.

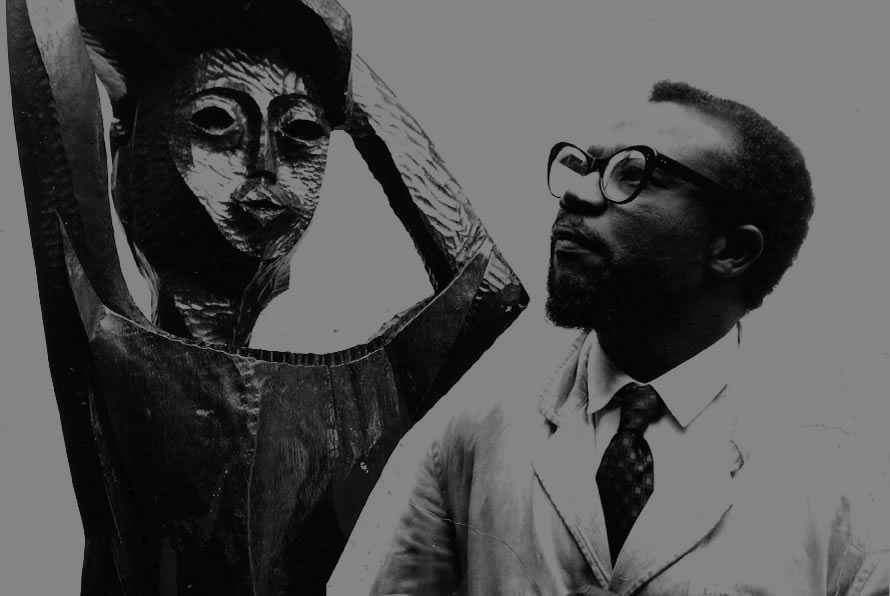

Ben Enwonwu © The Ben Enwonwu Foundation

On the occasion of the centenary of Ben Enwonwu, one of Nigeria’s most notable artists from the early modernist period, international scholars from Nigeria, the US, and Europe converged at Tate Modern. They gathered to address issues around the formation of post-colonial identity, the preservation of history in West Africa, as well as the impact of transnationalism and decolonization in arts education, art criticism, and museum collections today. Supported by Yvonne Alexandra Ike and Aigboje and Ofovwe Aig-Imoukhuede, two prominent Nigerian collectors, and with Chika Okeke-Agulu as keynote speaker, this conference also included contributions from a younger generation of scholars who addressed the history of Nigeria’s modernism and the legacy of its proponents in multi-dimensional ways.

During the course of the conference primary sources were closely examined and examples of past scholarship scrutinized. Okeke-Agulu focused on Ben Enwonwu’s most striking sculpture, Anyanwu (1956), a major symbol for Nigerian Independence. And Oliver Enwonwu, son of the artist and head of the Ben Enwonwu Foundation, divulged new insight into the importance of spirituality in African art. Audience members included renowned academics like John Picton, who served as the first director of the National Museum of Lagos in 1957, Charles Gore, Neil Coventry, and representatives from all the major auction houses.

Ben Enwonu, Anyanwu, 1956, bronze statue, National Museum Lagos, Nigeria, Photo: Bea Gassmann de Sousa

The most striking outcome, to say it in Emmanuel Iduma’s words, was that not only vulnerabilities of established theories were laid bare but also of personal doubts and questions about cultural details, source material, and omissions in historical accounts. Isabelle Malz from K21 called it “double-lack,” referring to women artists in worldwide collections but also to the works of notable Nigerian female artists which had simply disappeared. In the second day’s closing session, a conversation between Isabelle Malz and two representatives of the Fisk University Galleries in Nashville, Jamaal Sheats and Nikoo Paydar, revealed that three of the “missing” paintings by Clara Ugbodaga Ngu were in fact part of the Fisk University Galleries’ collection, courtesy of the Harmon Foundation collection. It was noted that another painting is located at Birmingham University in the UK. The whole event was peppered with such revelations and was framed by Chika Okeke-Agulu’s powerful appeal to Nigerian and global institutions and academics to pursue, value, and respect thorough, accurate, and detailed scholarship above all.

Politics and coloniality were at the heart of a number of the contributions referencing transmodern and transnationalist theories. It was discussed how the Biafran War – with Matthew Lecznar linking Appadurai’s “scapes” to Ben Enwonwu’s works from the war era – colonial indirect rule, liberal and neo-liberal capitalism, and auction markets all have an impact on the terms “African” and “modernism” as signifiers. Ozioma Onuzulike from Nsukka University added his sharp observations of Micheal Cardew’s attempt to “improve” the highly developed modernist Nigerian ceramics during the colonial era, confirming that Nigerian scholarship is also shaping the transnational debate from within.

Ben Enwonwu, Storm over Biafra, 1972, oil on canvas, collection of the National Museum of African Art – Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Copyright Ben Enwonwu Foundation

Another first was the re-tracing of links between the African and Black American civil rights struggles and the archivally documented connections between members of the Harlem Renaissance and African modernists during the 1930s, brought into focus by Christian Kravagna. He shed light on the relations between Black and White American artists during the segregation era and the development of a far more globally inclusive lineage of art references at the heart of Hale Woodruff’s mural The Art of the Negro at Howard University.

The discussion also raised questions about institutional integration and infrastructure, addressed both historically by Alinta Sara in her lecture about Négritude and the Ecole de Dakar, and from a contemporary perspective in William Rea’s suggestion of digitization and online archives to circumvent infrastructural problems of museums in Nigeria. The conference was brilliantly summarized by Nigeria’s future generation of artists. Folakunle Oshun, the curator of this year’s first Lagos Biennale (14 Oct.-22 Nov.), asked whether Nigerian artists actually still wanted to be identified as African rather than global citizens. Hopefully the years to come will provide us with the answers to this and other questions.

Bea Gassmann de Sousa is the founder of the Agency Gallery, London and an independent curator and researcher. She curated the exhibition A Portrait in Fragments: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (1951-82) with works from her archive. Since 2015 she has been researching manuscripts at the family archive of The Ben Enwonwu Foundation, Nigeria.

More Editorial