Maria Ines Plaza Lazo bears witness to Catlett's artistic skill and commitment to social justice in the late artist’s most comprehensive show to date.

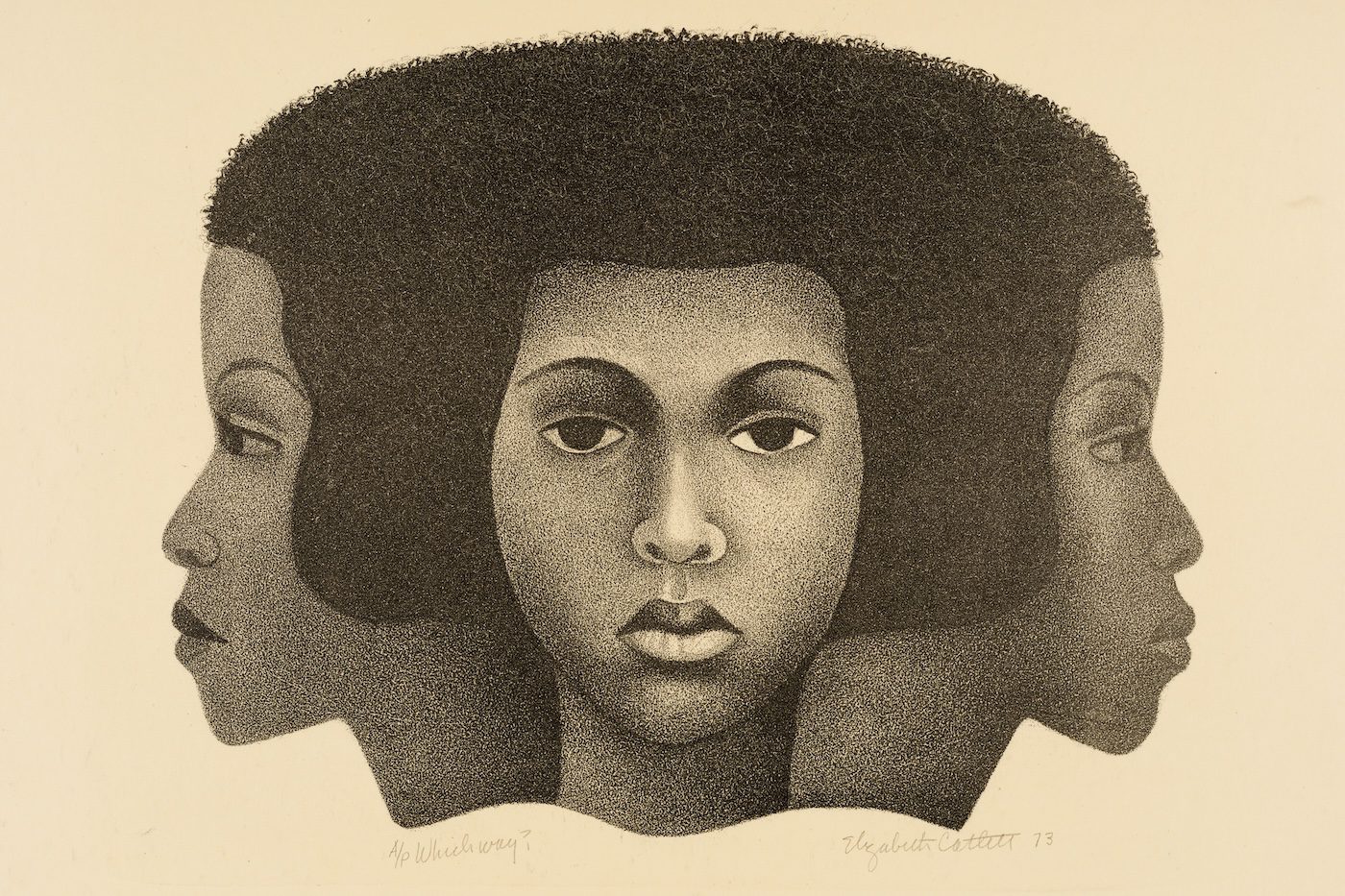

Elizabeth Catlett, Which Way, 1973, Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust, Mexico, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023 Elizabeth Catlett, photo: Axel Schneider

The figure’s eyes have no pupils. Its meticulously patterned hair perfectly abstracts its countless curls, the grainy surface of the skin, the voluminous nostrils and lips. Each of aesthetic choice here carries a strong relation to a feminist spirit, a deep knowledge of African ancestry, and a political consciousness of resistance against racism. One gaze containing all these notions opens up the exhibition of Elizabeth Catlett at TOWER MMK, a dependance of Frankfurt’s MMK in the financial district of the city.

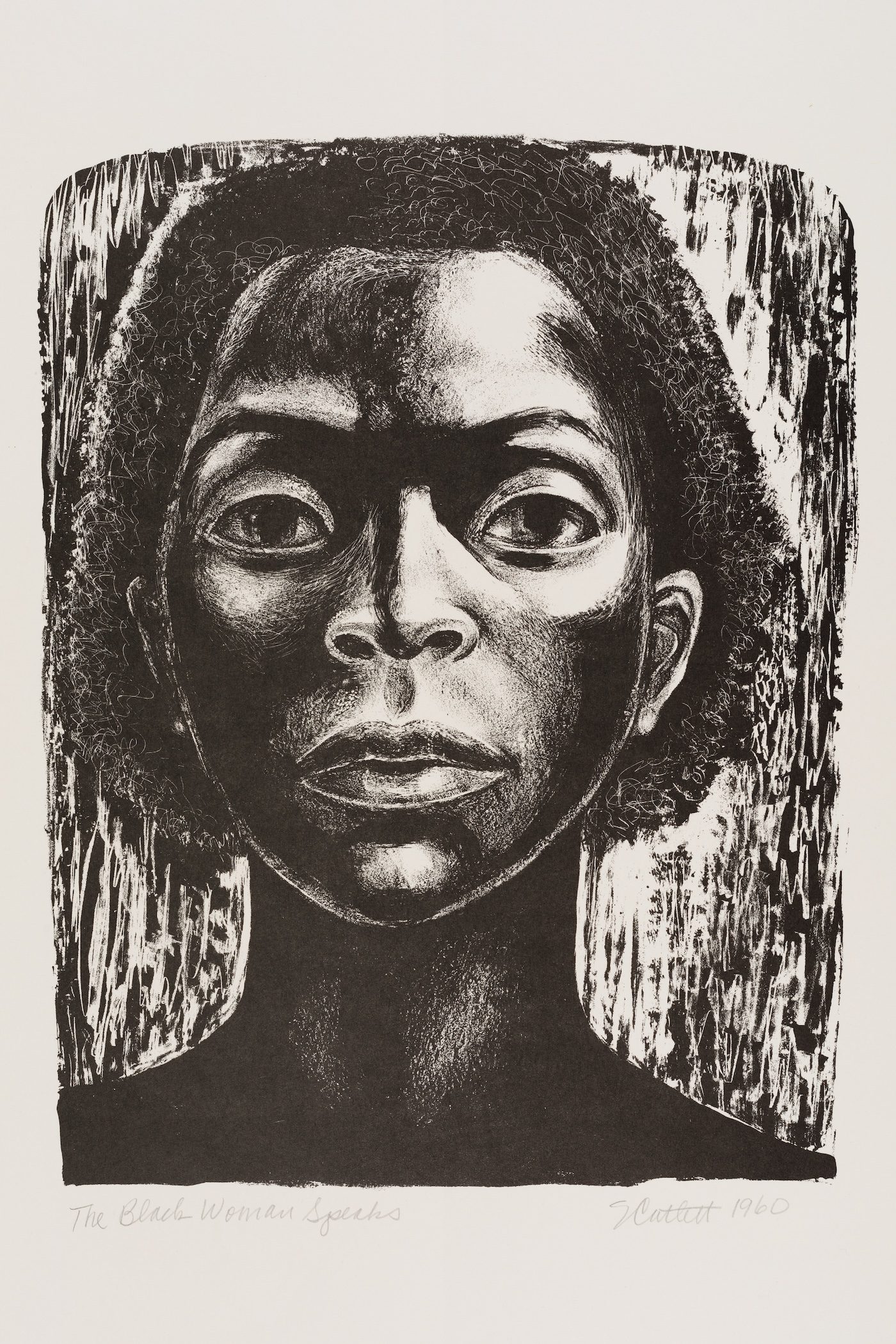

Elizabeth Catlett, The Black Woman Speaks, 1960, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, photo: Axel Schneider

This is the most comprehensive exhibition so far around the work of one of the most iconic Black women artists from the US. It further unfolds the profound exploration that scholars such as Melanie Anne Herzog and Humberto Moro have established in the academic context, as with the exhibition Moro co-curated on Catlett’s legacy at the SCAD Museum of Art’s Evans Center for African American Studies in 2021. The Studio Museum in Harlem, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture in Baltimore (2019–20), MoMA, and the National Museum of African American History & Culture have since displayed Catlett’s work in context of their respective collections.

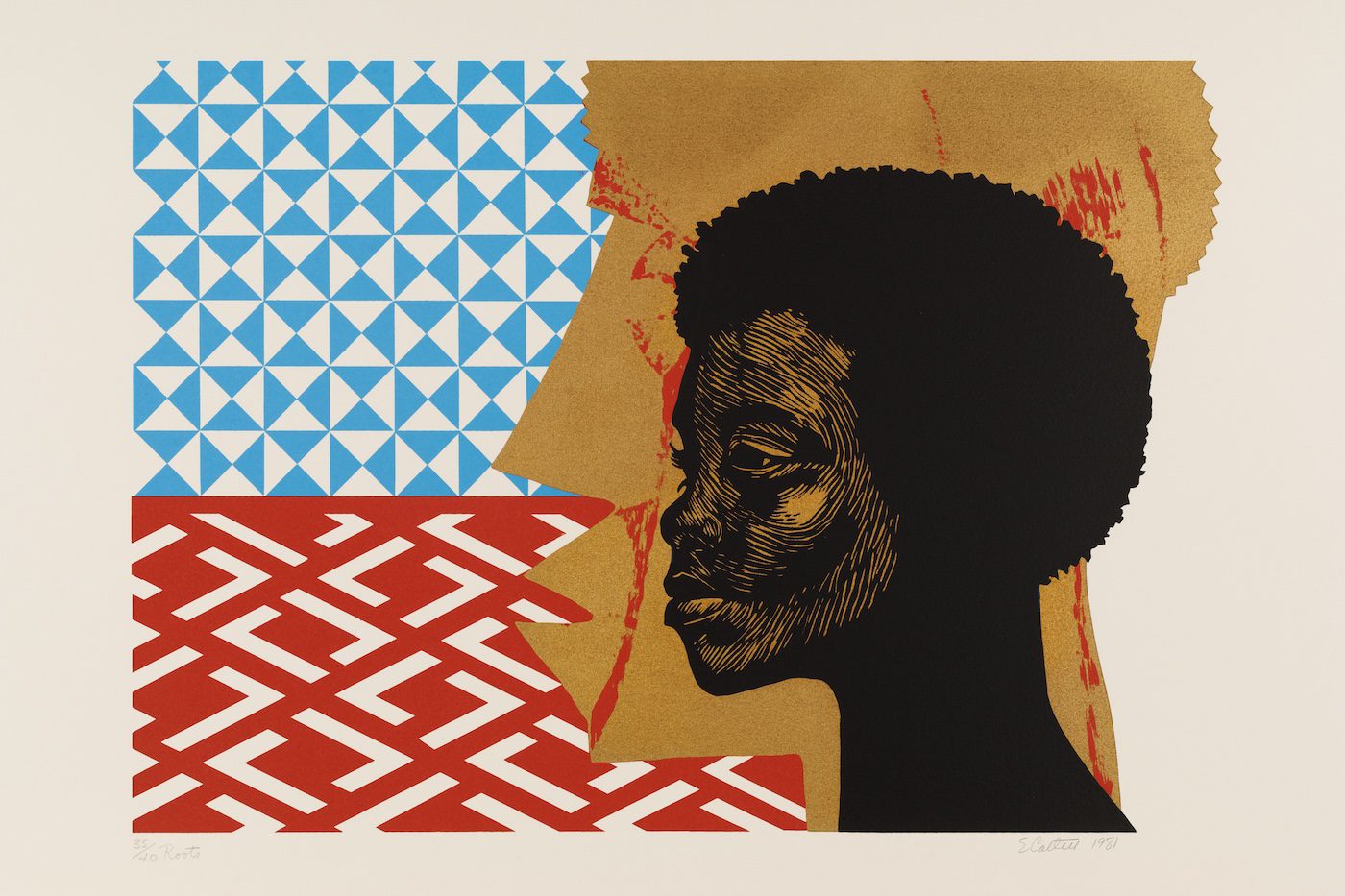

Elizabeth Catlett, Roots, 1981, Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust, Mexico, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, photo: Axel Schneider

With its intricate threads of resilience, identity, and social justice, the exhibition at MMK TOWER shares the sobriety of Herzog’s exhaustive academic work on Catlett yet is also topped with the meta-discursive precision that curator Susanne Pfeffer gives to every show she brings to MMK, always interrogating what museological collections should be for. Following the bold manifestation that turned TOWER MMK into a space of this sort of fundamental questioning – Cameron Rowland’s Amt 45i, for example, and the elegant display of entire reservoirs of marginalized figures such as Stephane Mandelbaum – Catlett’s exhibition presents a calm and clear chronological route through her entire career.

Elizabeth Catlett, In Harriet Tubman I Helped Hunderds to Freedom, Nr. 2, 1946–1947, Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust, Mexico, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, photo: Axel Schneider

The work is displayed in a way that holds on to the tensions between the role of museums, the act of exhibiting, and understandings of how things can be in space, while each artwork – regardless of size, material, uniqueness or multiplicity, or even stage of production – can be embraced as a document of history and exemplary case of artistic excellence, which Catlett determinately looked for throughout her life. MMK TOWER thus becomes the space of a Black feminist and activist who proudly held on to the history that had been passed on to her. Through lithographs, woodcuts, and sculptures, with utmost care for form and craftsmanship, Catlett captured the essence of African American heroines like Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, as well as everyday women in moments of vulnerability and strength. Catlett knew that skillful rigor would allow her works to transcend mere representation, serve as beacons of empowerment, offer visibility to those whose stories were often overlooked in the broader cultural narrative, and position herself among other artists.

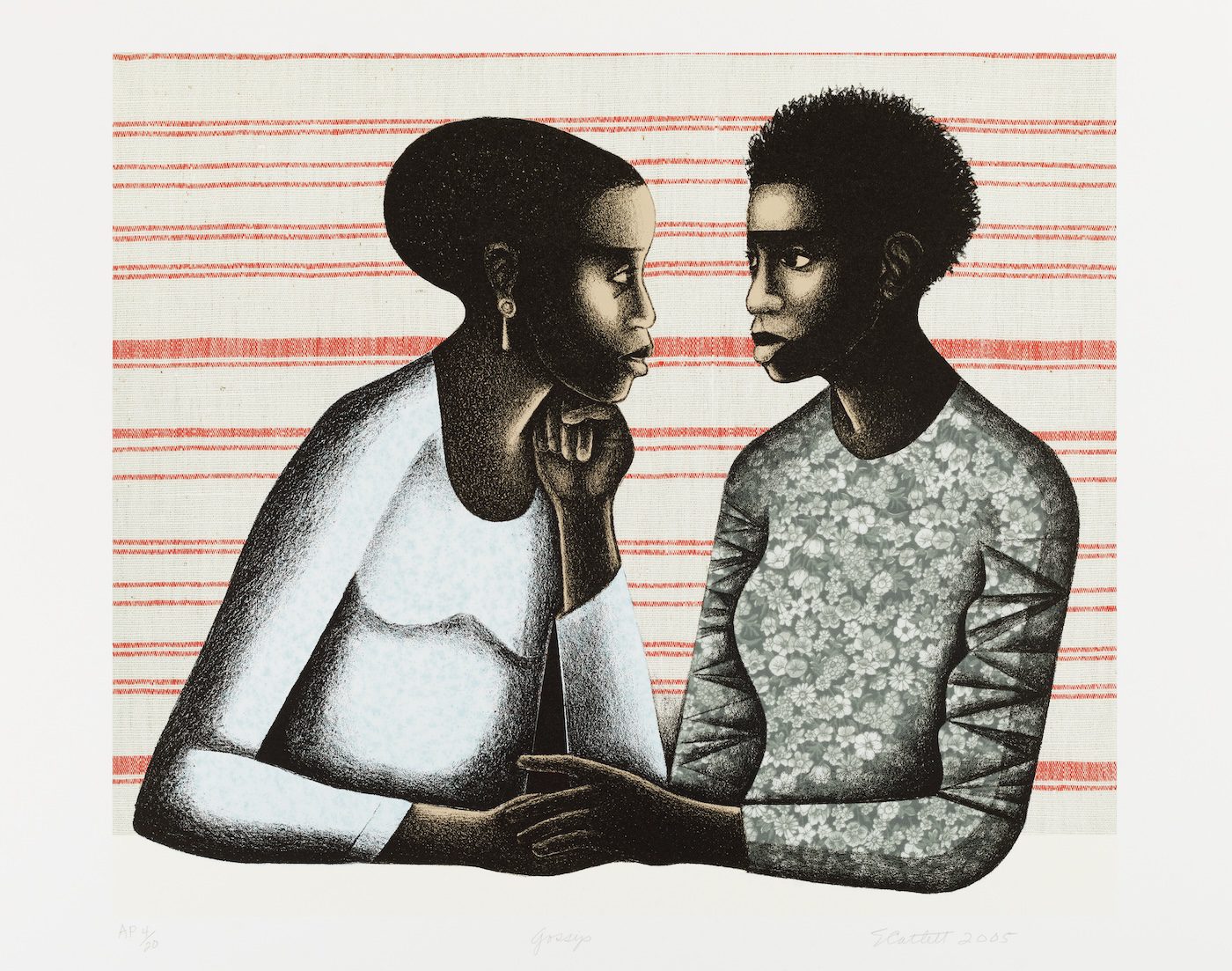

Elizabeth Catlett, Gossip, 2005, MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, photo: Axel Schneider

Every period of Catlett’s career is divided spatially by colors that respond to the compositions of what are predominantly portraits, inviting viewers to engage with the broader implications of her art on historical, aesthetical, and sensorial levels. The series In Other Folk’s Homes, from The Black Woman (formerly The Negro Woman), published first in 1946–47, brings us straight to the social injustice borne by Black domestic workers. While women are the protagonists of these woodcuts exhibited on white walls, we are also confronted with the brutality of racism towards Black men with the almost abstract depiction of lying lynched body, titled And a Special Fear for My Loved Ones. It served at the time as a stark reminder of why many people migrated from the South to the Northern United States, but also of the incessant difficulty Black people to continue to face in the form police violence. Catlett would come back to this figure in collages related to her remote support of the Black Panthers, remote because she was forced to move early in life to Mexico, due to the obstacles she faced as a brilliant Black artist, and later prohibited to travel home due to her political affiliations.

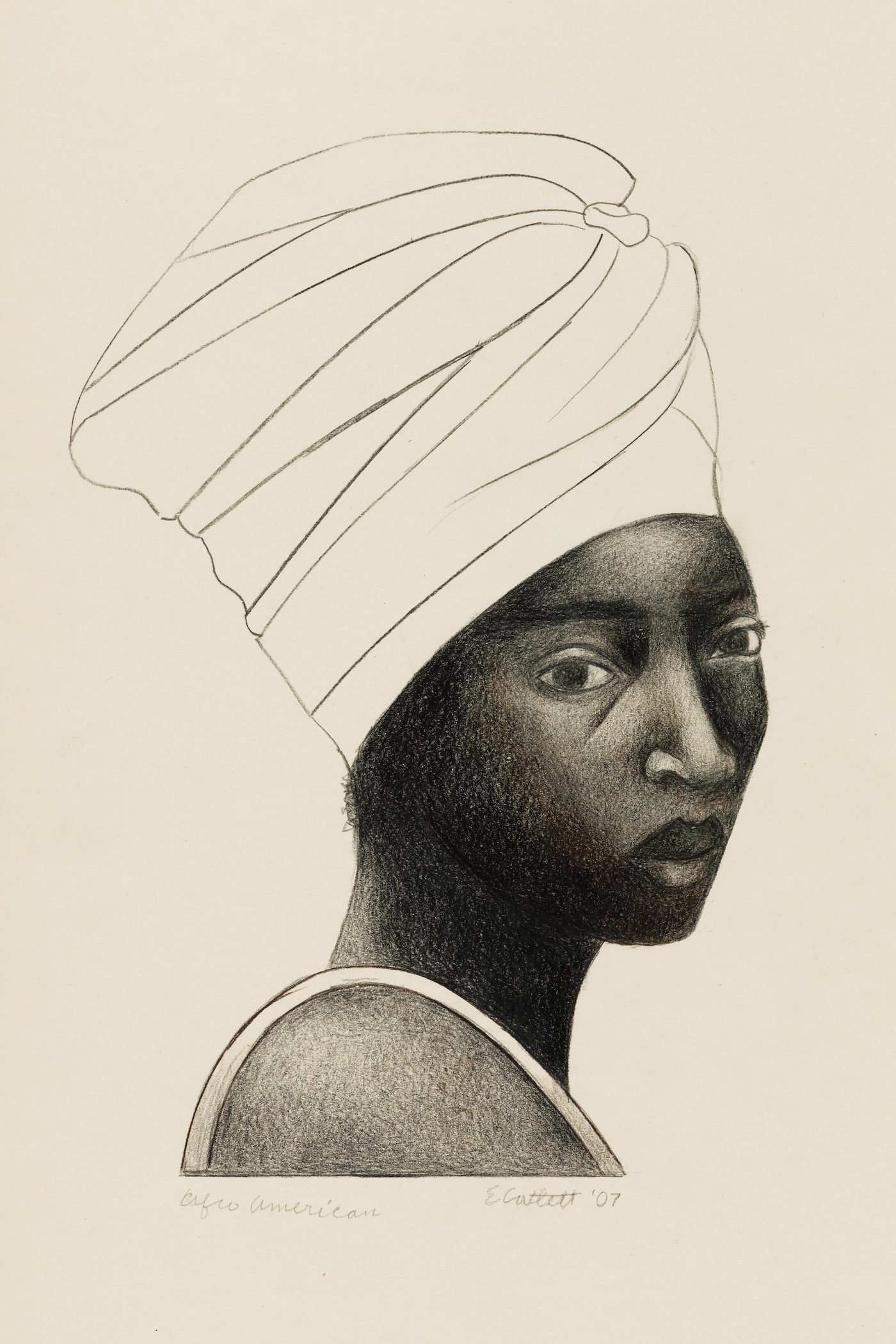

Elizabeth Catlett, African American, 2009, MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, photo: Axel Schneider

Catlett’s words, drawings, and sculptures eloquently highlight her commitment to the struggle of working people, which unfolded through her practice as an artist and educator in Mexico. She became a Mexican citizen in 1962 and made the print workshop Taller de Gráfica Popular her home, deepening herself in collaborative processes, in various graphic styles, and in new patterns reflecting intercultural organizations and her affiliation with unions and agricultural workers’ associations. Shown on warm terracotta-colored walls, a series of drawings and prints from that time are devoted to oppression across national boundaries and her consciousness of the intersection of race, gender, and class.

If activism and social consciousness form the core of Catlett’s work, her commitment to conceptual experimentation and technical skills also remained ever-present. In 1958, Catlett became the first woman professor of sculpture at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Mexico’s oldest and most prestigious art academy; she remained as chair of the sculpture department until 1975. At TOWER MMK, rooms in dark turquoise let the sculptures from this and later periods dance with each other. Intertwined political, social, and aesthetic narratives manifest materially and immaterially through her sculptures, staged on tailor-made pedestals of playful heights and widths. Each sculpture lets the visitor approximate its bold forms and powerful expressions, making monuments to the resilience and strength of a community long marginalized and oppressed. Our pleasure-driven gaze caresses each curve and surface that emanates the joy of being in place.

Elizabeth Catlett, We Three, 1969, Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust, Mexico, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, photo: Axel Schneider

Dark purple and melon beige walls bear further portraits and collages that assemble loose observations in visual cultures with the late eclecticism of someone who has nothing else to prove to herself. These works prompt us to contemplate the importance of representation, the transformative potential of storytelling, and enduring struggles for equality. Passing through the last rooms, I realized that Catlett’s impact cannot be confined by borders or generations. In examining her legacy, the MMK confronts the resilience of the human spirit and the transformative potential of art in shaping our collective consciousness.

MMK TOWER thus presents a living archive that traces the evolution of an artist who remained committed to social justice throughout her ever-evolving artistic expression. Honoring Catlett’s impact on the intersectional understanding of today’s art practices and discourses, Pfeffer navigates that complexity without putting herself at the forefront. A concrete example of this is the exhibition brochure, which focuses only on the wonderfully accessible and thorough essay by Herzog that gives all the context needed for the exhibition to be enjoyed in critical reflection.

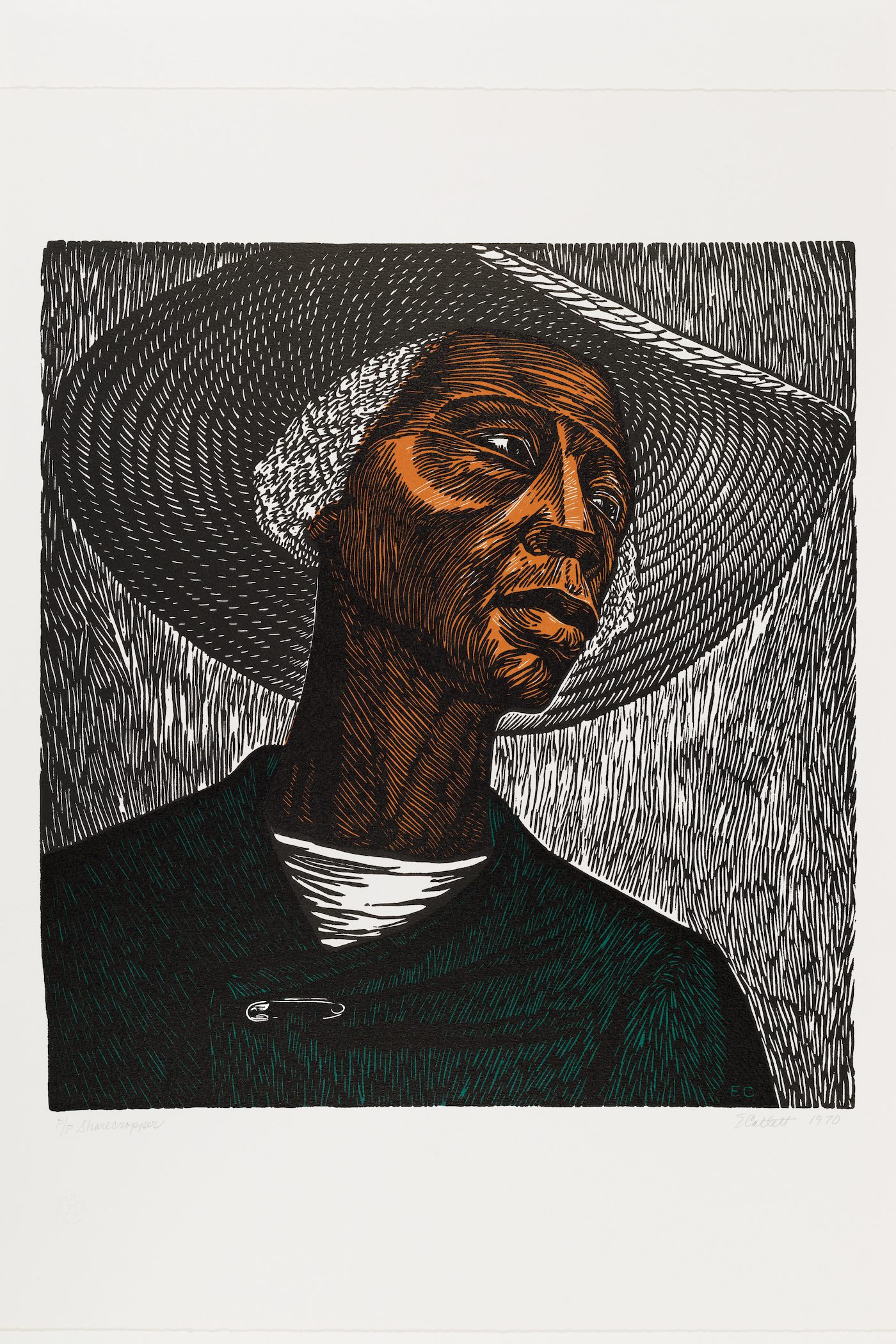

Elizabeth Catlett, Sharecropper, 1952/1970, MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST, © Elizabeth Catlett Family Trust / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023, photo: Axel Schneider

Catlett’s timeless works force us to grapple with uncomfortable truths and imagine a more just and equitable world. The exhibition serves as a poignant reminder of our shared humanity and the imperative to confront injustice with courage and compassion, ideals that Catlett upheld throughout her life. It is with this embodied liberty that she speaks to other female protagonists shown at MMK over the past five years. I remember the tears that came to my eyes when I saw Victoria Santa Cruz’ Me llamaron Negra (They called me Black) occupying an entire wall and entire room of Pfeffer’s first collection display, titled MUSEUM, all in capitals – a display that introduced the MMK’s responsibility to focus on everything but a Eurocentric canon. Since that moment we have seen presentations of younger artists such as Precious Okoyomon, Lungiswa Gqunta, the Critics Company, and Helena Uemembe, who are not only protagonists of a different way of defining an exhibition space, but are also reclaiming visibility and reassociating history with the marginalized of the world in the present.

Elizabeth Catlett doesn’t merely add depth to this ongoing celebration of artistic prowess and human generosity; it is a profound testament to the enduring power of art as a force for social change. Calett’s legacy endures, and this exhibition propels a call to action for generations to come.

Elizabeth Catlett is on display at TOWER MMK until 16 June 2024.

María Inés Plaza Lazo is a founder and publisher of Arts of the Working Class, the multilingual street newspaper for art and society, wealth and poverty from Berlin. She just started working at the Kunsthalle Baden-Baden on communications strategies for the institution, at the intersection between curating, publishing and public relations.

FEMALE PIONEERS

More Editorial