Stories of Almost Everyone at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles engages with various modes of communication. Curator Aram Moshayedi and curatorial assistant Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi talk to C& about the delicate communication between artists and institutions and how their exhibition transpired.

Installation view of Stories of Almost Everyone. Photo: Joshua White

C&: How did the exhibition come about?

Aram Moshayedi: There are a few trains of thought that gave way to Stories of Almost Everyone. In part, it came about as a way of avoiding the problems of thematic exhibitions and the pitfalls of organizing things according to a logic that may be external to the work. For one, this exhibition focuses on the ways in which we discuss and characterize the fundamental thinking about art objects. But it’s also about the ways in which this experience is framed by institutional practice and curatorial oversight. A work like Instantly enveloped by water, the surface closed above my head, I understood how my body made the sea level rise (2017) by the Dutch collective gerlach en koop exemplifies what I mean here.

C&: The exhibition focuses on art that uses everyday objects. It made me think of Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (1929), where she recommends that we “think of things in themselves.” Is that something you intended with the exhibition?

Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi: If I recall, Woolf’s narrator spends a day at the British Museum, sitting with its weight of knowledge, attempting to write about “Women and Fiction.” She doesn’t look at art objects, but at literature. After being met with countless texts of mansplaining though, she realizes that locating truth is next to impossible if sought without questioning and generating one’s own story. And even after reflecting on her own lot – her inheritance, the affective baggage of patriarchy – she still questions its relevance to her task at hand: writing about “Women and Fiction.” For our exhibition this questioning and self-reflexivity is generative. Possibilities arise when focusing on things, the self, but there are also limits in the knowledge we must reckon with.

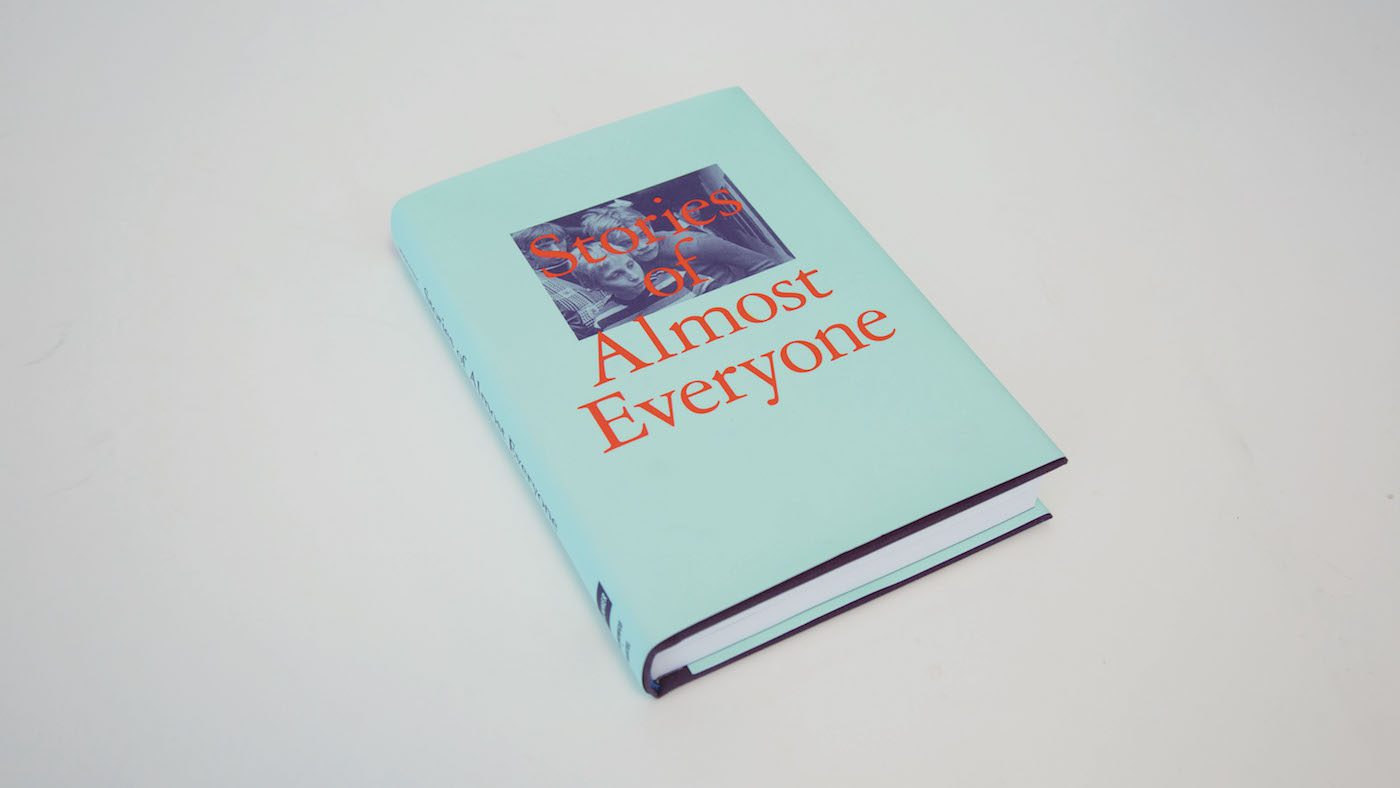

Exhibition catalog for Stories of Almost Everyone, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, January 28-May 6, 2018. Catalog design by Joseph Logan Design, distributed by DelMonico Books/Prestel. Photo: Chisa Hughes.

C&: Aram, in the exhibition catalogue you talk about the desire for meaning in art, for narrative – what exactly do you mean?

AM: The role of storytelling is only a small part of Stories of Almost Everyone. Within this context however it’s interesting to think about how ideas are communicated between an artist and an institution, how there is a responsibility of conveying the intentions of an artist while also remaining committed to one’s own curatorial interests that are often broadly defined. The expectation to relay these ideas resembles oral histories being passed on. It’s our responsibility to convey these ideas without suffocating them or making them too absolute for an audience who, at least in the US context, is already generally suspicious.

In the case of our exhibition, the wall labels are decidedly conspicuous, the introductory panel is self-conscious, and there is a short video of a Japanese confidence man by Jay Chung and Q Takeki Maeda that takes on the task of greeting visitors. A museum guard performs a striptease according to the parameters of a work by Tino Sehgal titled selling out, and there is an alternate account of the exhibition by writer Kanishk Tharoor that is available in the form of an audio guide. These interventions address the modes of mediation that are intricately tied to the experience of exhibitions today.

C&: Do you see the curating of an exhibition as a way of storytelling?

AM: I think, in general, of exhibitions as a form of writing. Storytelling is less interesting to me, but writing as a process of thinking is key. Curators tend to want to be storytellers because this allows for the cultivation of mythology and the like, but maybe they (myself included) should also spend more time being writers.

IO: Echoing Aram, and holding dear the advice of my mentor Adrienne Edwards, the writing process that precedes an exhibition is crucial in helping one identify one’s stakes in the work, as well as catch any blind spots in one’s thinking. Aram and I both write not always to tell stories, but to think a thing through.

C&: Ike, in the catalogue you wrote an essay about dance as a way to approach the art object. Do you consider this a way to make one feel and experience art instead of using language as an interpretative tool?

IO: Yes and no. Dance is just another language operating alongside word-based modes of communication. So while I’m interested in the postures and behaviors we take up when we look at art, I’m equally drawn to how this dance engages other sensual faculties. Movement isn’t divorced from other senses. And I’ve gravitated towards Tina Campt and Fred Moten on this inseparability. Campt aligns body movement to listening, and Moten’s “sensual ensemble” begins, yes, with listening, but contends that any aural act is bound up in what we see, smell, or feel. So we might begin with dance, but let’s also momentarily sit with what Moten calls the blur, which is what happens when we get up close with an art object and stay there without immediately stepping back to zero in on the wall label. By embracing this blur in dance and sensual reception we forgo attempts at describing a work in strict terms.

C&: You also refer to Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God…

IO: Right. In a way, Hurston’s description of Janie “going inside there to see what it was” addresses this blur or how we locate the sensual ensemble within ourselves after attending to an object, especially one whose provenance escapes us. To that point, Janie didn’t necessarily know what “fell off the shelf inside her,” which speaks to not only avoiding descriptive specifics for the speculative, but the intrigue to step into and dance in that realm.

An Paenhuysen works as a freelance curator, art critic and educator living in Berlin. She is a fervent art blogger and teaches art criticism online at Node Center for Curatorial Studies.

Stories of Almost Everyone is running until May 6 at the Hammer Musuem Los Angeles.

More Editorial