Adji Dieye: The Symbolisms of Seasoning

29 April 2020

Magazine C& Magazine

Words Elisa Pierandrei

7 min de lecture

Adji Dieye is a transmedia artist living and working between Zurich, Milan, and Dakar. Shown internationally, from Dak’art to Kunsthalle Wien, her work explores cultural representations in public space and focuses on Diasporic and West African identities. With Elisa Pierandrei she discusses the exploitative economic dynamics between Africa and the West and how the stock cube became the central object of her photographic series Maggic Cube.

Contemporary And: On what terms and meanings do you build your aesthetic and reflexive narrative about our current times?

Adji Dieye: My irritation. Irritation toward the languages and forms of representation inhabiting the public sphere that inevitably influence our perceptions of ourselves and the way we socially interact. Also the irritation of navigating a Western society whose only medium for understanding my appearance and my identity is the externalization of my existence. Misguided cultural production in public forms of communication and representation is the core element of my life-long irritation.

Over the years, I’ve tried to explore ways to convey this feeling into something fertile. I’ve pushed myself to learn where and how I could point the finger at the source of my irritation – while transforming it into the counter-voice of itself.

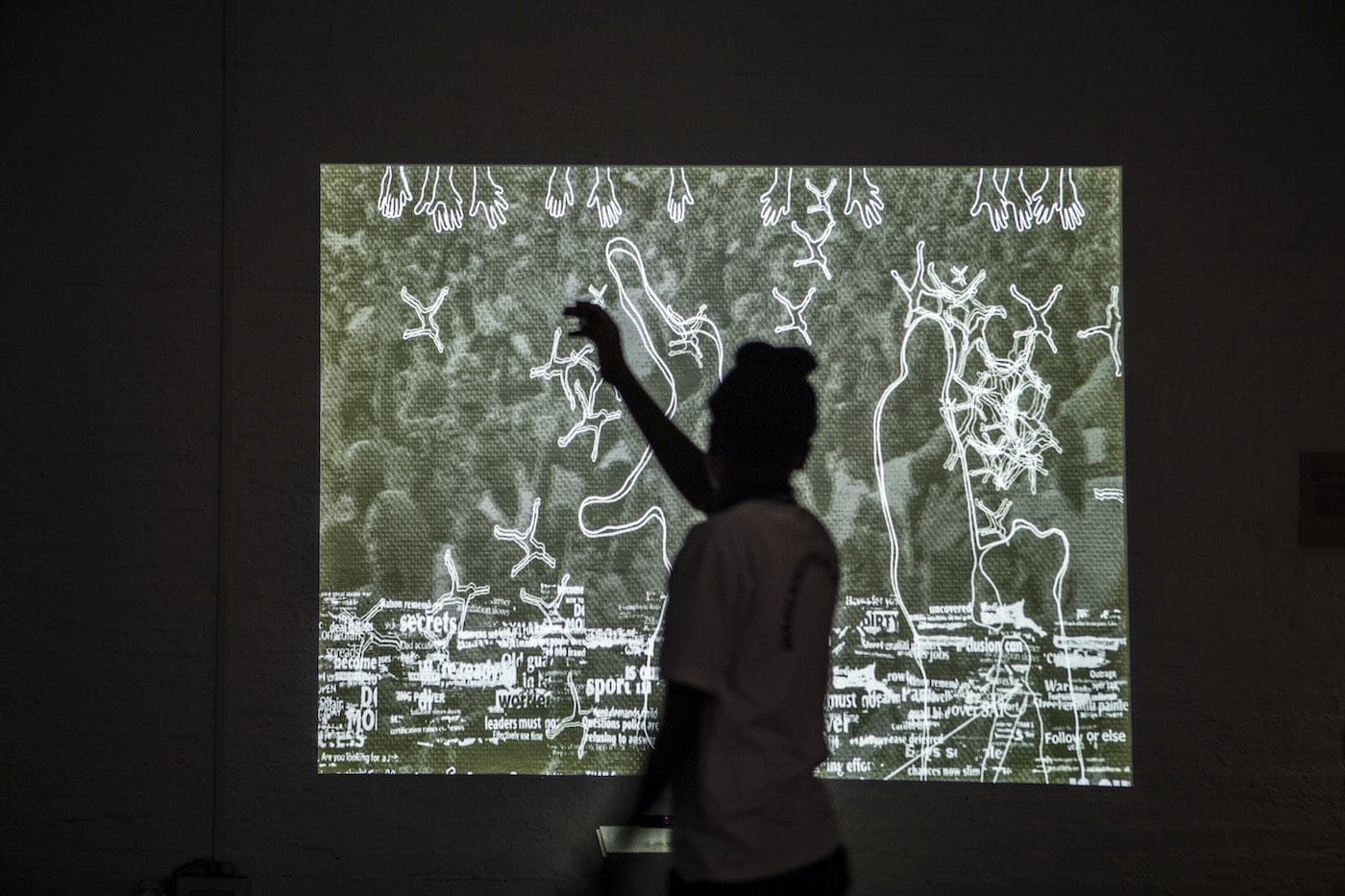

Adji Dieye, Maggic Cube. Courtesy the artist.

C&: Wishing to unveil the impact of certain goods imported to West Africa, you have looked at the symbolism of the stock cube. Can you introduce the photographic series that resulted?

AD: Started in 2015, Maggic Cube was the result of my research into the notion of branding and its influence in the production of visual culture, from urban landscapes to contemporary art. I’ve focused my investigations on Dakar – my second native city – where advertisements for stock-cube brands are omnipresent.

Now owned by Nestlé, Maggi products first entered the African market right after the Berlin Conference in 1885, when European powers decided upon the geographical and economic fate of the African continent. Since then, stock cubes have become a key ingredient in many West African cuisines, and earned the nickname “magic” cubes.

My images repurpose the hunger-inducing reds and yellows used by brands such as Maggi and Jumbo, while their compositions reference master photographers like Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita. Combining the visual languages of food advertising and portraiture was also a way to highlight how the contemporary art economy often reduces the visual cultures of West Africa into a singular “style” – reflecting the same consumerist attitude of branding strategies toward culture. Here, a banal product such as the stock cube becomes a vehicle for a multi-layered discussion.

</p>

By loading the video, you agree to Vimeos’s privacy policy. Learn more

Always unblock Vimeo

</p>

</p>

</p>

PGRpdiBjbGFzcz0iX2JybGJzLWZsdWlkLXdpZHRoLXZpZGVvLXdyYXBwZXIiPjxpZnJhbWUgc3JjPSJodHRwczovL3BsYXllci52aW1lby5jb20vdmlkZW8vMTcxOTAzOTk1P2RudD0xJmFtcDthcHBfaWQ9MTIyOTYzIiB3aWR0aD0iNTAwIiBoZWlnaHQ9IjI4MSIgZnJhbWVib3JkZXI9IjAiIGFsbG93PSJhdXRvcGxheTsgZnVsbHNjcmVlbjsgcGljdHVyZS1pbi1waWN0dXJlOyBjbGlwYm9hcmQtd3JpdGU7IGVuY3J5cHRlZC1tZWRpYTsgd2ViLXNoYXJlIj48L2lmcmFtZT48L2Rpdj4=

C&: The series Maggic Cube also comprises a film titled Circuit Fermé, which was shot in Milan. Could you explain what the film is about?

AD: Given their historical presence in countries like Mali, Senegal, and many others, companies like Maggi have facilitated the creation of (un)sophisticated languages conveying the idea that the stock cube is are one of the most traditional elements of West African cuisines—as such, a prominent example of neoliberal capitalism.

In the short video performance Circuit Fermé we see a young man, Alyoub, strolling around in the weekly market in my neighbourhood of Isola in Milan, attempting to sell these famous “magic cubes.” The work is born out of an ironic attitude toward appropriating a space through the selling of goods. We hear the protagonist’s voice from a megaphone; it invades the surrounding space. We can see Alyoub sonorously appropriating the public sphere and enacting a symbolic gesture of returning the stock cube to its birthplace by selling it back to the European continent.

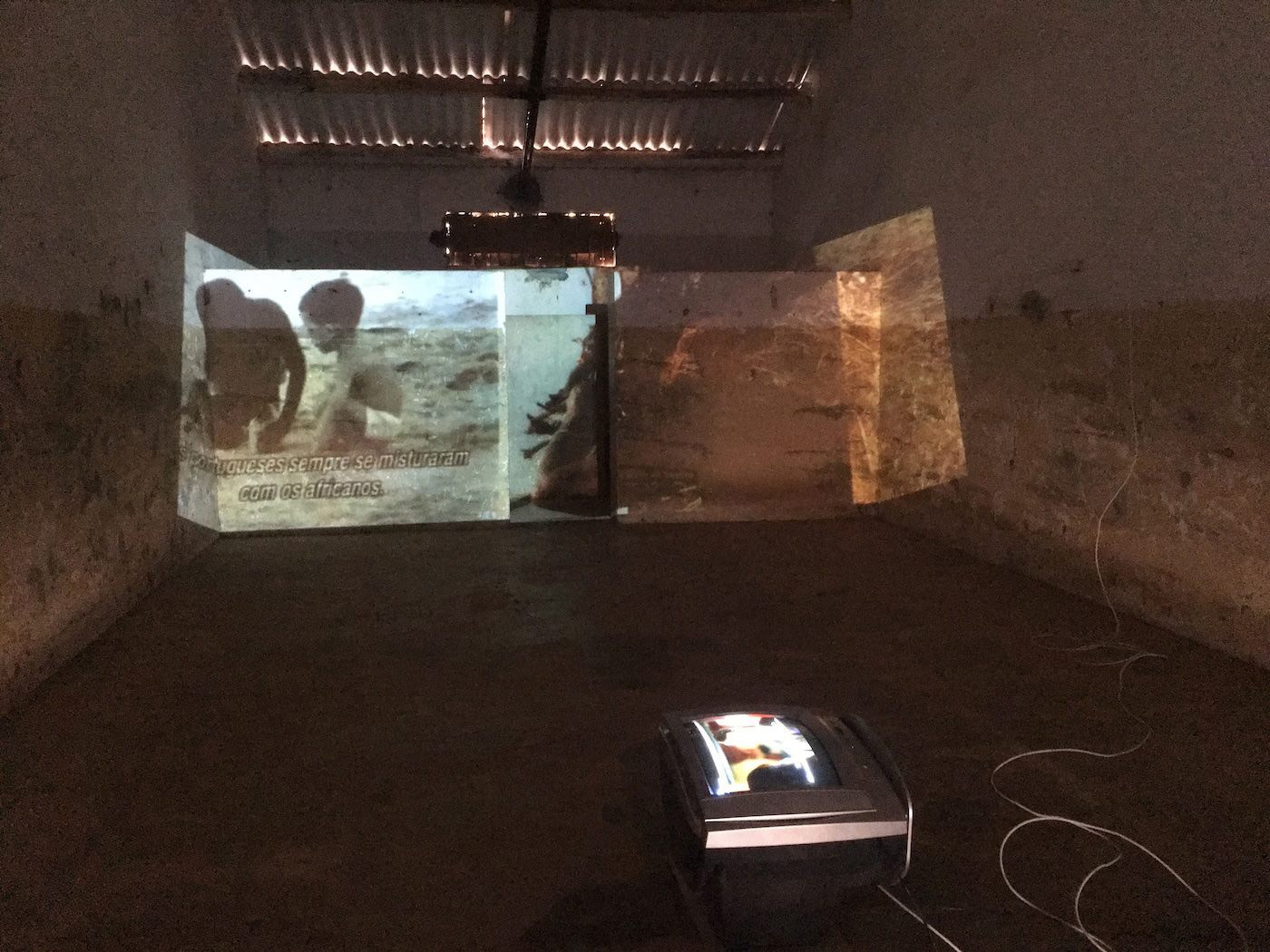

Red Fever by Adji Dieye. “Sporcarsi le mani per fare un lavoro pulito” curated by BHMF, Murate Art District, Florence.

C&: What are some of the key factors that have fed into your research lately?

AD: I would say the notion of temporality and our relationship to dominant historical narratives when confronted with anticolonial practices. I recently wrote a thesis titled “Culture Lost and Learned by Heart: The Post-colonial Archive as a Construction Site in Contemporary Art.” I think the title clearly sums up my field of research.

C&: Could you give us a portrait of your family in black and white?

AD: In a context dealing with the artistic practices of Afro-Italian artists, asking for a portrait of one’s own family reiterates the same difficulties and issues that black Italians have to go through daily, from the moment we have our first social interaction.

What I mean is that asking me to make a black and white portrait of my family implicitly reformulates the same form of curiosity that us black Italians are continuously subjected to… you’re Italian, but why are you black?

As if the Italian citizenship embodied by a black body would necessarily hide an intriguing story to share. In some situations it might even be the case that the uncomfortable position that such a request poses to us is one of needing to uncover an entire family biography in order to be understood by the majority other.

This process of constant estrangement unconsciously and consciously refutes the existence of the duplicity of national and cultural identities, using the origins as a form of delegitimization of the others own identity.

In this context, my choice of refusing to uncover my family’s history and my black origins is not a form of denial of who they are but rather a deliberate choice to use my body, my artistic practice and my Italian passport as a political gesture against this perpetuated process of estrangement that non-white Italians have to go through.

My family biography doesn’t inform the understanding of my work, rather it limits it to a sociological curiosity which I refuse to give.

Adji Dieye, Maggic Cube, Kunsthalle Vienna. “. . . of bread, wine, cars, security and peace”, curated by WHW, What, How & for Whom. Vienna, Austria 2020.

C&: What are you working on now?

AD: Given the current unprecedented circumstances, I’m working on readjusting myself to the state of quarantine. For the first time in contemporary history, we are challenged on a global level to make a collective yet individual act of resilience and mutual aid, which places each of us in a position of having to think through different future possibilities for ourselves and our societies, while assisting at the collapse of present infrastructures.

Cultural producers in contemporary art need to create space to finally reimagine systems. It was already happening, but this might give it a boost. I wonder what the future of the art world will be like, especially for up-and-coming artists like myself. Is this going to be the time in which a diversified structure for the arts will be established? Will it be based on different artistic methodologies rather than a rigidly capitalist system? The very system that is constantly discussed in theory but very well practiced in our art economy, and which fuels a commodity understanding of cultural matters? Concerning university art programs, what are we left with when our access to workshop facilities and studios are denied? The switch to an e-learning system that has led students around the world to revolt, asking for a tuition-fee refund, speaks loudly about what needs to be reconfigured when talking about art infrastructures.

I also reflect a lot on my own practice these days. And I engage in a project named (Post)Coronialism, initiated by Jessika Khazrik, an artist, electronic music producer, writer, and technologist from Lebanon who is now confined in Berlin. (Post)Coronialism is an open collective study, solidarity, and strategy group that commonly works on the demilitarization of health, education, and other sectors, the comorbidity of capital, and the urgent spread of interdisciplinary care.

Adji Dieye is an artist living and working between Zurich, Milan, and Dakar. Dieye holds a BA in New Technologies of Arts from the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera in Milan and a MFA degree from the Zurich University of the Arts, ZHDK.

Elisa Pierandrei is a journalist and author based in Milan.

Plus d'articles de