Sudan’s cultural memory has long been under attack —added to decades of state censorship are the effects of the devastating ongoing war that began in April 2023. As museums are looted and studios destroyed, the Sudan Art Archive, led by Reem Aljeally and a network of artists spread from Khartoum to Muscat, has recently emerged with the aim of both memorializing art, stories, and identities erased on the ground and facilitating solidarity in the diaspora. Through digital preservation, and with an eye on the future, it hopes to reclaim narrative power in exile – one pixel at a time.

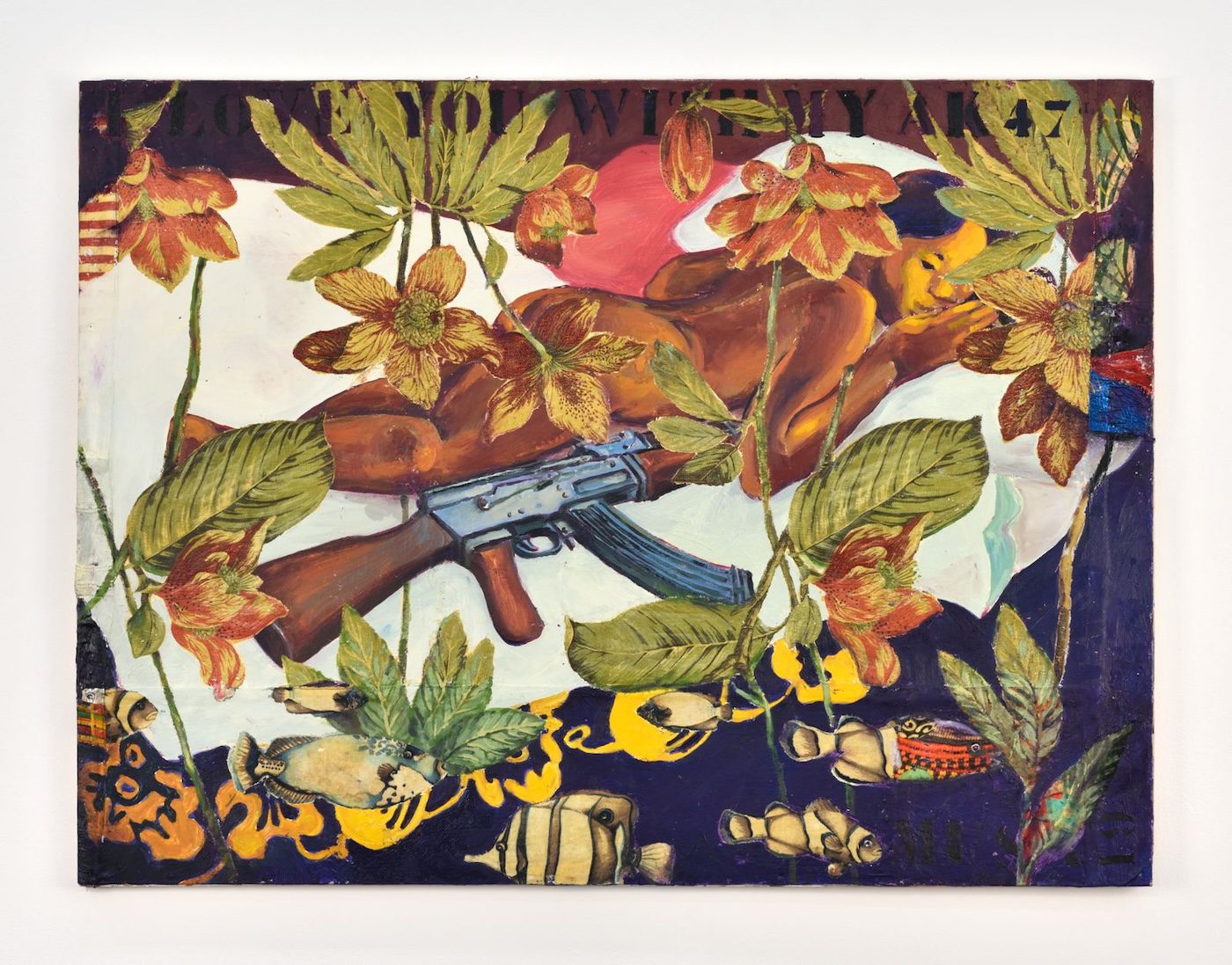

Hassan Musa, I love you with my AK47(1), 2019. Oil on printed fabrics on wood, 121 cm x 190 cm. Photo courtesy of the Galerie Maïa Muller.

Attacks on Sudan’s collective memory have a long, painful historical thread, dating back to British colonial occupation and peaking during Omar Al-Bashir’s three-decade rule. The National Islamic Front systematically targeted intellectuals, artists, and national records, enforcing a monolithic Islamist-nationalist narrative that erased diverse identities. Just as healing began after his ouster in 2019, the war between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and Sudan Army Forces (SAF) erupted on 15 April 2023, unleashing new violence not only against the general population but against culture —cultural centers, galleries, and the Sudan National Museum have faced demolition and looting. Amid this maelstrom, the digital realm might seem to offer the only possible refuge for Sudan’s heritage. It is with this idea in mind that the Sudan Art Archive (SAA), a project by the Muse Multi Studios —based between Sudan and Egypt – launched this February at Cairo’s Arab Digital Expression Foundation with the aim of digitally preserving Sudanese visual art production since 1975.

Launching the Sudan Art Archive on 25 February 2025. Courtesy of SSA.

Khartoum, the capital city whose diverse architecture and unique social life stem from its dual foundings (1824, 1910), holds irreplaceable layers of Sudan’s cultural memory. In destroying the creative hubs that flourished post-Al-Bashir, the current war leaves Sudan’s physical archive and its living architectural records facing an unknown fate. « Khartoum has not been spared,” says artist Mohammed Ohaj. “The city has endured devastation that has altered its features, making it unrecognizable. As an artist aware of the dangers war poses… I lost my personal studio and artworks that represented a personal legacy to me. » Artist and curator Reem Aljeally, who founded Muse Multi Studios in 2019 and is SAA director, was among those who saw the critical need for digital preservation —a refuge not just for artworks but their crucial contexts.

The revolution of 2018–19 and the periods that followed allowed for a slight liberation in cultural expression, including the concepts of archiving and documentation, away from the narratives sponsored by Al-Bashir’s government. This also contributed to shaping awareness of archiving among Aljeally and her colleagues. « Artists’ communities and contributors are the ones who shape narratives about themselves and their communities,” she says – and the Sudanese must control their archives in the digital era.

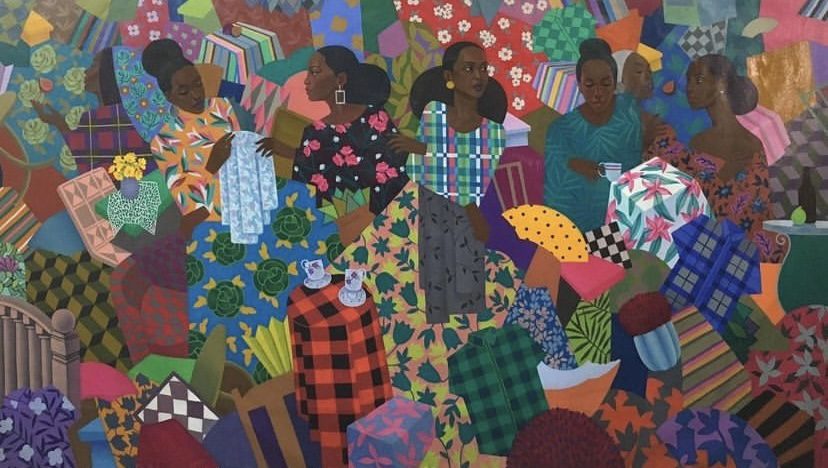

Mohamed Abdhamid Abdgadir Saeed, Marketplace, 2020. 131×231cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Supported by Culture Resource, A.M. Qattan Foundation, Ettijahat – Independent Culture, Aflamuna, and L’Art Rue, the SAA’s mission is based on a resilient and global diaspora. The idea has been there since 2022, but crystallized after the outbreak of the war. With the state unable to protect cultural assets, Sudanese artists, curators, and archivists in exile, from Cairo to Nairobi and then across the Middle East, started collaborating to rebuild a canon.

Yasmin Abdullah, an artist displaced to Muscat, Oman, describes how the war impacted her artistic life: “It reshaped my perspective on art documentation and archiving. After the outbreak of the war, I lost more than forty works of art —some without a single photograph… That moment made me realize the urgency of preserving not only our art, but also our cultural memory and emotional heritage.” This same urgency drives the meticulous work the SAA has begun of scanning, cataloguing, and collecting oral histories in an attempt to compile a comprehensive art history. Abdallah herself now creates art shaped by nostalgia, longing, and a deep connection to Sudan, to give space for stories to live on and provide a form of solidarity and continuity for fellow artists in exile.

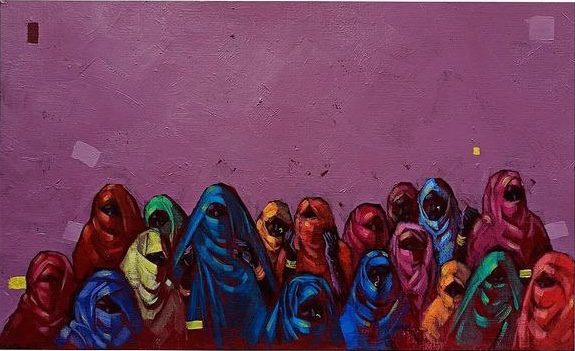

Yasmeen Abdullah, I DON’T KNOW SOLD THE COUNTRY, BUT I KNOW WHO PAID THE PRICE, 2021, Acrylic on canvas 100*88cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Ohaj, who has contributed to SAA, believes that the project came at the right time to save Sudanese art from ruin. He also thinks it is possible to compile a history of Sudanese art within a single framework that preserves it and creates a bridge between artistic generations —even introducing them to each other. This reflects a broader experience, as Ohaj notes from his involvement in the Extended Cities group exhibition held this year at Cairo’s Medrar, which explored displacement and identity between Khartoum, Port Sudan, and Cairo —mainly the shared experience of displacement and refuge in cities radically shaped by construction and destruction. This collaborative spirit also forms the basis of the diaspora’s documentation efforts. (Members of the diaspora could also obtain artwork from their country as they attended the exhibition.)

The SAA aims to transcend mere storage to be a resistance instrument and dynamic tool that can be shared online to foster solidarity in exile. For me Abdullah’s own archived works, inspired by Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry, exemplify this. She explains that her work To the Enemy Who Drinks Tea in Our Hut (2022) “speaks to the bitter betrayal felt by Sudanese people, those whose homes were occupied… It quietly reflects how normal routines can continue, even as people go through this pain and disruption.” Her works, such as another titled I Don’t Know Who Sold the Country, But I Know Who Paid the Price, gently remind us that “ordinary” people always bear the heaviest burden. For Abdullah, these works are her “way of continuing a lost conversation with Sudan.”

Mohammed Ohaj, Untitled, 2022. 25*25cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Ohaj remains optimistic: “This war has reshaped our narratives, our ideas, and our consciousness. I hope we come back stronger than before, able to express ourselves through art and beauty.” Born out of necessity, the Sudanese Art Archive should become both a monument and an act of resistance. It hopes to democratize access to Sudan’s artistic past, wresting it from historically unreliable state control. While Aljeally and her team face enormous challenges, their work highlights how memory can be a powerful weapon against erasure, and the archive a revolutionary act. But it also prompts urgent questions, such as: Who controls the online narrative? How can an archive serve as both memorial and resistance? And how can we ensure that digital records survive and remain accessible in the long term? In the meantime, SAA is not just preserving art but helping to protect the soul of the nation, continuing Sudan’s vibrant cultural heritage, ready to inspire the rebuilding that is yet to come.

Butros Nicola is a South Sudanese freelance feature writer and storyteller with a keen interest in the interplay between arts, culture, and social issues. Nicola’s published works examine experiences of conflict, displacement, modernization, and migration in South Sudan and Sudan, providing nuanced narratives that illuminate the human consequences of these transformative processes.

ART IN CRISIS

C&’s second book "All that it holds. Tout ce qu’elle renferme. Tudo o que ela abarca. Todo lo que ella alberga." is a curated selection of texts representing a plurality of voices on contemporary art from Africa and the global diaspora.

More Editorial