Victor Ehikhamenor is one of Nigeria’s most vibrant contemporary artists. He is currently taking part in the 57th Venice Biennale as Nigeria joins other nations in attending the event for the first time. C& spoke to Ehikhamenor about his practice, exchanges with his colleagues, and the relatively new appreciation for artists from the continent.

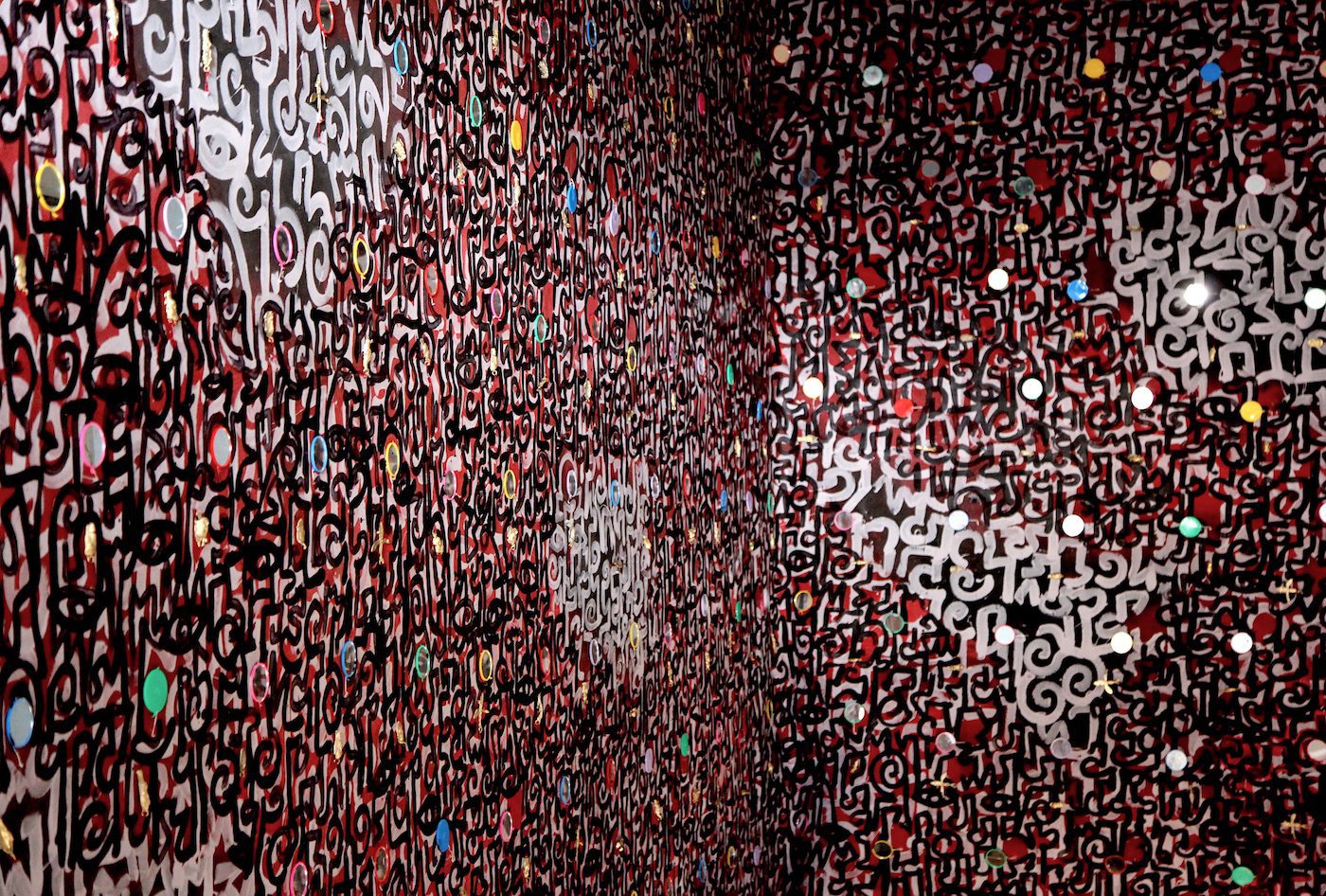

Victor Ehikhamenor, A Biography of the Forgotten, 2017. Installation view at Nigerian Pavillion, 57th Venice Biennale. Courtesy of Tyburn Gallery.

Agwu Enekwachi: You were recently in Abuja for a talk with artists. What was the core of the message you came with?

Victor Ehikhamenor: I was there to share my experience with other artists, both young and older, and also to learn from them. I am mindful of the need for this kind of exchange between artists because it is very easy for people to think that it only rains in your own part of the universe. Nigeria is a huge country and this was an opportunity to reconnect with my friends in Abuja and with those whose careers I’ve watched over the years. Being there for me was a continuation of the conversation between artists, which, no matter how small, can always lead to something or somewhere.

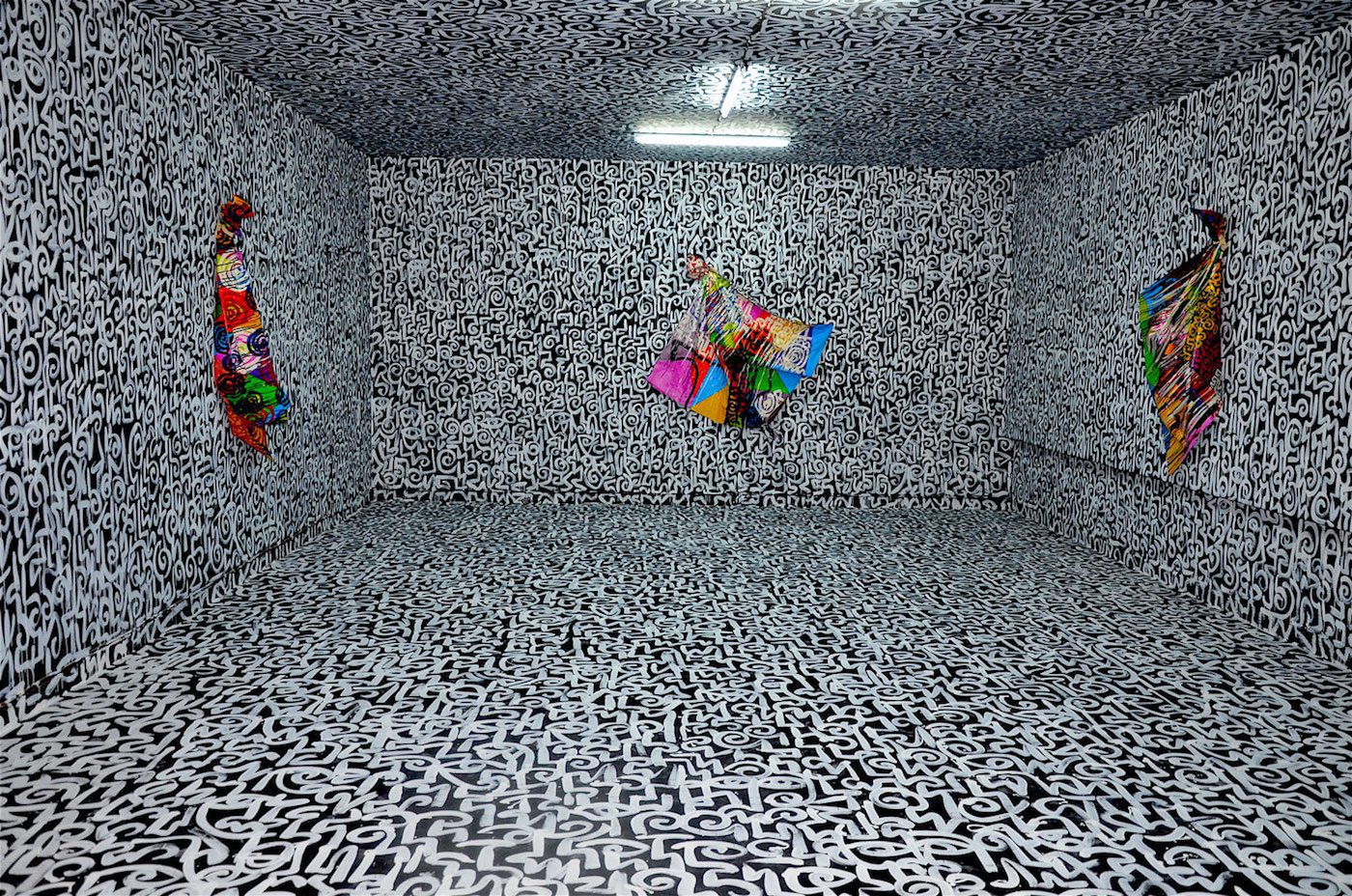

Victor Ehikhaemnor, Prayer Room, 2016, Installation view at 12th Dak’art Biennale, dakar, Senegal. Courtesy of Tyburn Gallery

AE: The title of your artist talk was Neo–Natural Synthesis. What was that all about?

VE: My talk was anchored on the inspiration I gained from Uche Okeke. I read a lot about him and his contributions to Nigeria’s postmodernism: his vision to leverage the local content we have always had with us and his emphasis on the purity of intuition as a force for originality in the pursuit of creative excellence. This is the power behind my art practice. As you may know, I did not train in a conventional art school; everything for me comes naturally from the inside. I relate deeply with Uche Okeke‘s thoughts and practice because they significantly fertilize my ideas and help me find my creative direction. For me, this is the beginning of what I call Neo-Natural Synthesis. It is a new way of looking at and channeling the ideas of Okeke and his contemporaries who espoused the movement of Natural Synthesis. I want to pay deeper attention to the intrinsic ideas and look at my creativity through the prism of Natural Synthesis, however, not without incorporating the nuances of time. It is like using it as a lens to give focus to my creativity.

AE: Has your creative enterprise always referenced this idea of Neo–Natural Synthesis or is it a new development?

VE: I think about it less in terms of a movement or form of terminology, Neo–Natural Synthesis is just a description of my interpretation of the kind of work I am doing. I always reference memory, culture, and home. My background as an artist involves taking interest in the art activities happening around me: the local carvings in shrines and the paintings done by local artists. There is a similarity between my earliest influence and the way Okeke went back to his roots to pick elements from his culture. To me, the Igbo design tradition of uli is an open visual language that lends itself to adaptation.

AE: At what point did you discover your artistic voice?

VE: I don’t pay particular attention to milestones like that. What I strive for is to keep working without ceasing. Sometimes when you work you do not have a predetermined course, but as you keep making progress, you begin to have revelations and get clarity. About style – the way you walk, talk, and dress over time defines you. So it is with art practice. I do my work and over time my style has become clearer. It is like Chinua Achebe using idioms and proverbs, which became his style. I personally keep returning to lines and this has metamorphosed to include symbols and iconography, and I keep flowing with them. It is hard to say if this is the point where I struck the right cord. I have done several works in my career that are not in the public sphere, these works vary in style, content, and contexts, sometimes they are products of mere playfulness. I have always had a voice as an artist but the moment of discovery for me is the point of deciding to stick to a particular mode of expression. I think that is what I have done at this point, I have decided to stick to a thread and see how that will evolve.

AE: In your various channels of expression – writing, photography, and art – do you have a point of intersection or a common theme that runs through your works?

VE: These are different mediums and they present their uniqueness. Drawing and painting to me is like visual writing. Drawing some lines may equal writing two lines of poetry, but if I decide to fill an entire room with drawing or painting, it is like writing a 1000-page book. I decide if a canvas should have many characters or only one or two, like a short story. So, approaching my work from that perspective means that there is indeed an (un)conscious, seamless meeting of these platforms. I have also noticed that there is an intersection in the process of titling my works or writing about them. But I leave it to the critics to make readings of my various channels of expression. Personally, I view my writing as humorous and my drawings and paintings as more serious.

AE: What is your take on the growing global appreciation of art from African perspectives?

VE: It is encouraging that the appreciation of the art sector is growing. The continent has been waiting for this level of creative resurgence for far too long. A lot of people have worked hard to ensure that Nigerian and, by extension, art from African perspectives has gained this level of recognition although this does not apply to all artists. The current situation is welcome because it will create a value chain that will rub off positively. People will write about art, go into curatorial studies, there will be more investors, and there are a number of people planning to build private museums.

AE: How have your international engagements contributed to your career?

VE: It has been very helpful as an opportunity for the cross-fertilization of ideas. Regarding aspects like production, management, presentation, and critical analysis, there is a lot to take from such engagements. I consider interacting with other artists very important as it helps to sharpen my ideas and skills. For instance, my current space in Lagos was inspired by my visit to the expansive studio of Theaster Gates in Chicago. Today, my studio is not just for creating works but a space where young people have the opportunity to come and rub minds and interact with others, to engage in conversations and perhaps find directions. It is about expanding the community – locally and internationally.

Agwu Enekwachi is a PhD student in Art History at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He is a Sculptor, an art teacher and culture writer living in Abuja.

More Editorial