Academic and cultural producer Michelle M. Wright reflects on the current political situation in the US and how many women of color contributed to a moment of hope.

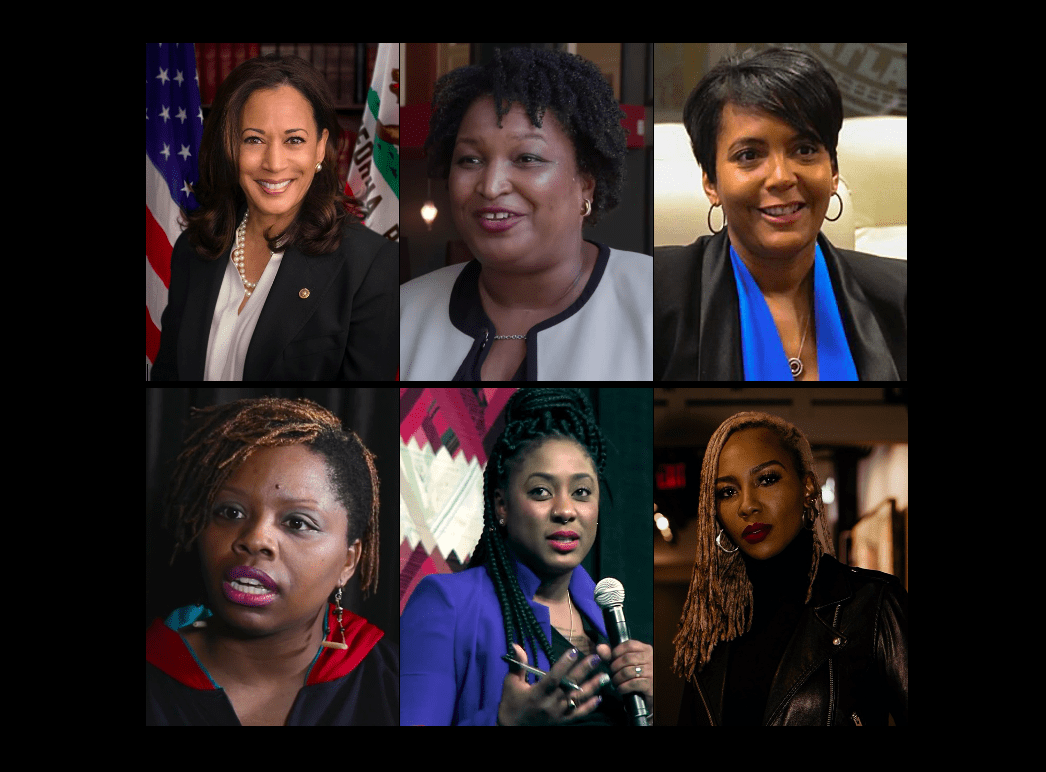

(clockwise) Kamala Harris, Stacey Abrams, Keisha Lance-Bottoms, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi.

You usually don’t see people streaming into the streets to celebrate an election—at least, not in the US. With the election of Barack Obama, the streets of Chicago filled and thrilled, but now it’s Chicago, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, New York City, a diverse sea of faces giddy with joy.

There we were, on a late Saturday afternoon, celebrating the election of a seventy-eight-year-old straight white man who had gained national notoriety in 1991 for enabling the Republicans’ character assassination of a Black woman, Anita Hill, in order to promote noted predator Clarence Thomas to the US Supreme Court.

To be fair, Joe Biden ran a smart campaign in impossible circumstances: in the middle of a pandemic, when wearing a mask was read by many as proof of moral decrepitude. He also won by important margins, all the more impressive when one considers the 72 million voters who turned out for Donald Trump, including 19% of Black and Latino men.

In Atlanta and the nation, our heroes of the day include organizer Stacey Abrams, who told us we could do it when we believed we could not; Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance-Bottoms, who did not back down from requiring masks and social distancing when threatened with legal action by the state’s Republican governor; Vice President-elect Kamala Harris, whose presence inspired first-time voters to vote; and, of course, Opal Tometi, Alicia Garza, and Patrisse Cullors, the founders of Black Lives Matter. All women of color, all hopeful and smart, all insisting that we must take the long view when it comes to seeking justice over injustice, acceptance over bigotry, love over hate, peace over violence.

This fight is far from over, and our victory is only partial. In many ways, Trump and US Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell have won, at least in the short-term long-term: the Supreme Court, for the first time since the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, is firmly packed with a radical right majority hostile to minority and women’s rights as well as fair and free voting. Republicans enjoyed victories in state legislatures, ensuring a voting district map that will continue to favor Republican candidates for many years to come. One former Obama pollster estimated that the Democrats would have to win at least 54% of the popular vote in future national elections in order to break even with Republican overrepresentation.

Some cling to the hope that the long-predicted and now unavoidable surge in COVID-19 cases will change public opinion, but at the moment Trump supporters are largely shrugging off the illness and even deaths coming into their towns. Like Trump, they argue that COVID-19 is no worse than the flu and, like the flu, some folks will inevitably die from it. For them, wearing masks and “closing down” the economy is to be feared more than death. Increased partisanship has gripped our nation and elsewhere, including Canada, Mexico, South America, and Europe. Those who believe vaccines to be poison and the earth to be flat are joining hands with QAnon followers. They are also streaming into the streets.

I don’t point all this out in order to hang my head wearily and encourage you to despair. Two things frighten me as an academic (well, actually, many more, but let’s keep this as impersonal as possible): being overly optimistic and being overly pessimistic. I fear sliding into a trough of ideology, opinion, and hand-picked statistics, and drowning in it. I fear that possibility because it’s a cowardly retreat, it is using one’s intellect without one’s creativity, one’s courage.

Creativity understands the Day After as the After-Day, a moment not marked as a conclusion but as a starting point informed by what has just passed. Creativity does not move forward, hoping to push our own little team ahead of those we despise; it moves outward. It is capacious and transformative, allowing for ourselves to change as we seek to change others.

Abrams lost the 2017 gubernatorial race in Georgia and started two non-profit organizations to fight voter suppression in the state; Kamala Harris lost her run for the Democratic presidential nomination and became vice president-elect; Tometi, Garza, and Cullors became incensed at the slaughter of African Americans at the hands of police and began a movement which, decentralized and open to change, is now worldwide—and was instrumental in bringing down Trump.

As women of color, we must be flexible in order to survive, we must comprehend and live according to truths that few are willing to acknowledge: that victims can also be oppressors; that those who are stirringly eloquent about their lack of privilege in one context can suddenly wield privilege in another context and be spectacularly, obtusely cruel about it. If we are to survive and to triumph, we must be outward-bound: creative, capacious, hopeful, resolutely changing, and resolutely transformative.

Michelle M. Wright is the Augustus Baldwin Longstreet professor of English at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia—now a “blue” state in the US.

She is the author ofBecoming Black: Creating Identity in the African Diaspora (2004) and Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology (2015). Writing through gender studies, queer studies, science studies, time studies, Black European Studies, African American Studies, and African Diaspora Studies, her work focuses on Black identity formation in both creative and academic discourses.

More Editorial