Riding the Waves of Time

30 April 2018

Magazine C& Magazine

6 min de lecture

Contemporary And (C&): How did you become involved with art? Oneika Russell: I just kept making choices based on what my heart told me to do. When I finished high school I was all set to go to the major university in Jamaica. But when nothing really excited me as a prospect for study, I …

Contemporary And (C&): How did you become involved with art?

Oneika Russell: I just kept making choices based on what my heart told me to do. When I finished high school I was all set to go to the major university in Jamaica. But when nothing really excited me as a prospect for study, I decided to put my university place on hold to try something new. I enrolled at the Edna Manley College of the Visual & Performing Arts for a year to see if that interested me. It obviously did as I completed my painting course and kept going. Because, if you do it long enough, you can’t help but think as an artist.

C&: What topics interest you particularly as an artist?

OR: What fascinated me from the beginning was that the possibilities are endless, that there are limitless media and processes to use. For this reason, much of my work uses both image and media exploration; technique and ideas. Even though I trained as a painter initially, other areas such as film, animation, moving image, comics, literature, and fashion have always held great interest for me. At times, in my animations and video work I am most interested in creating an experience that is sensory.

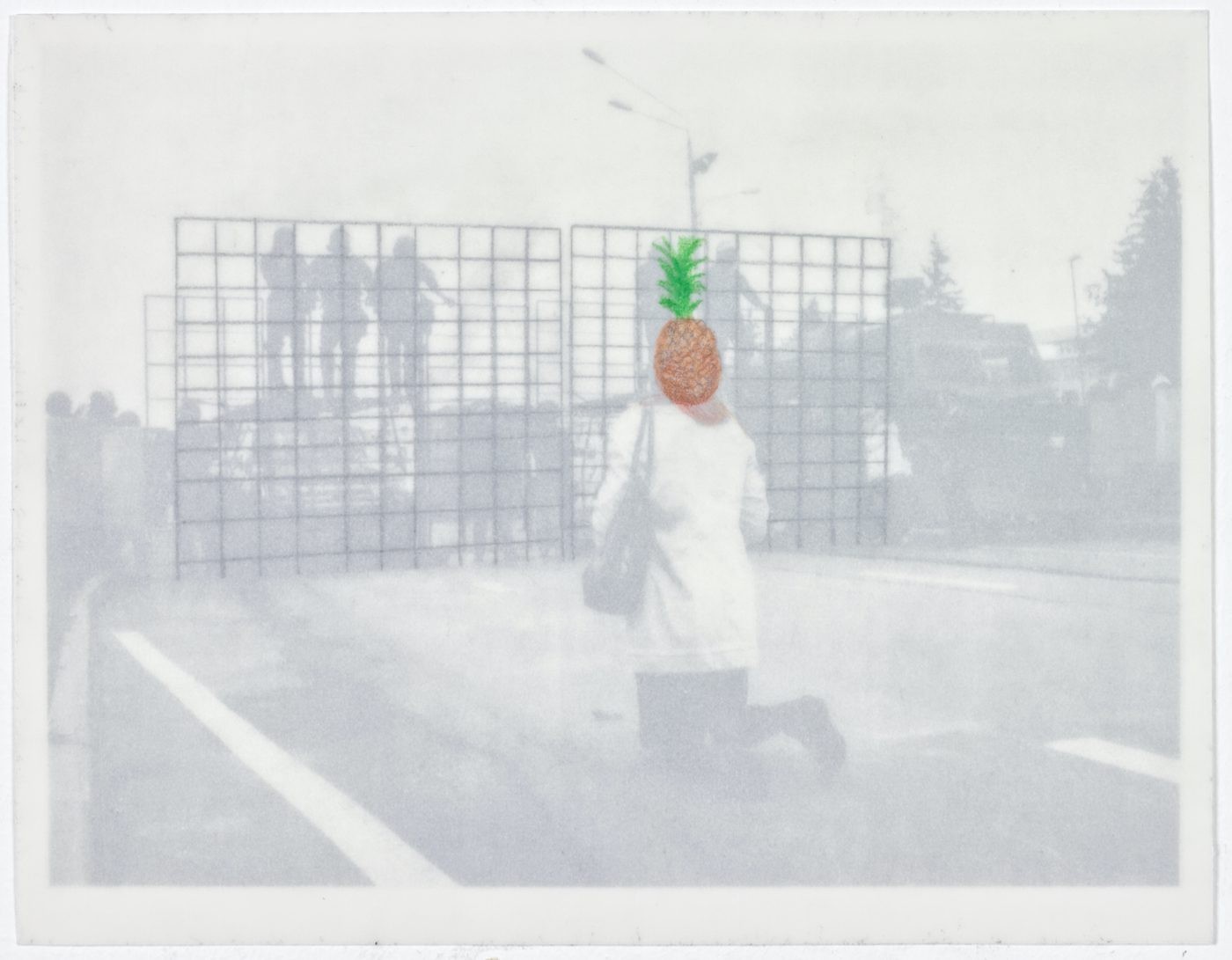

Screen shot from ‘A Natural History ‘ 4 sequence 2’, 2013

In a recent series of work, A Natural History, I explored the culture and identity of Caribbean people like myself. Our identity is often very specific in its hybridity but is also connected to older traditions and histories in both Africa and Europe. So, in this recent series of videos, drawings, prints, and artists book, I undertook to convert a photograph of myself into various creature-like figures. I wanted to use visual images to convey what it feels like to be dehumanized and detached from one’s identity.

C&: In what ways did you look at these detachments?

The Caribbean identity is often a strange but interesting space to inhabit. It is an experience which is tied to the idea of marketing our land, our bodies, and our culture. I am interested in the physicality of the space, in its beaches and lush greenery as well as the bodies that inhabit the space. I am also interested in how those in the Caribbean present themselves for consumption and how they are received as exotic and consumable. I’m interested in a hybridity that also extends to finding ways to combine traditional craft and digital processes. For example, how does one make a print which looks like a painting or an advertisement, and how can it also feel like a book or a film? How can you make an image which is both beautiful and uncomfortable at the same time?

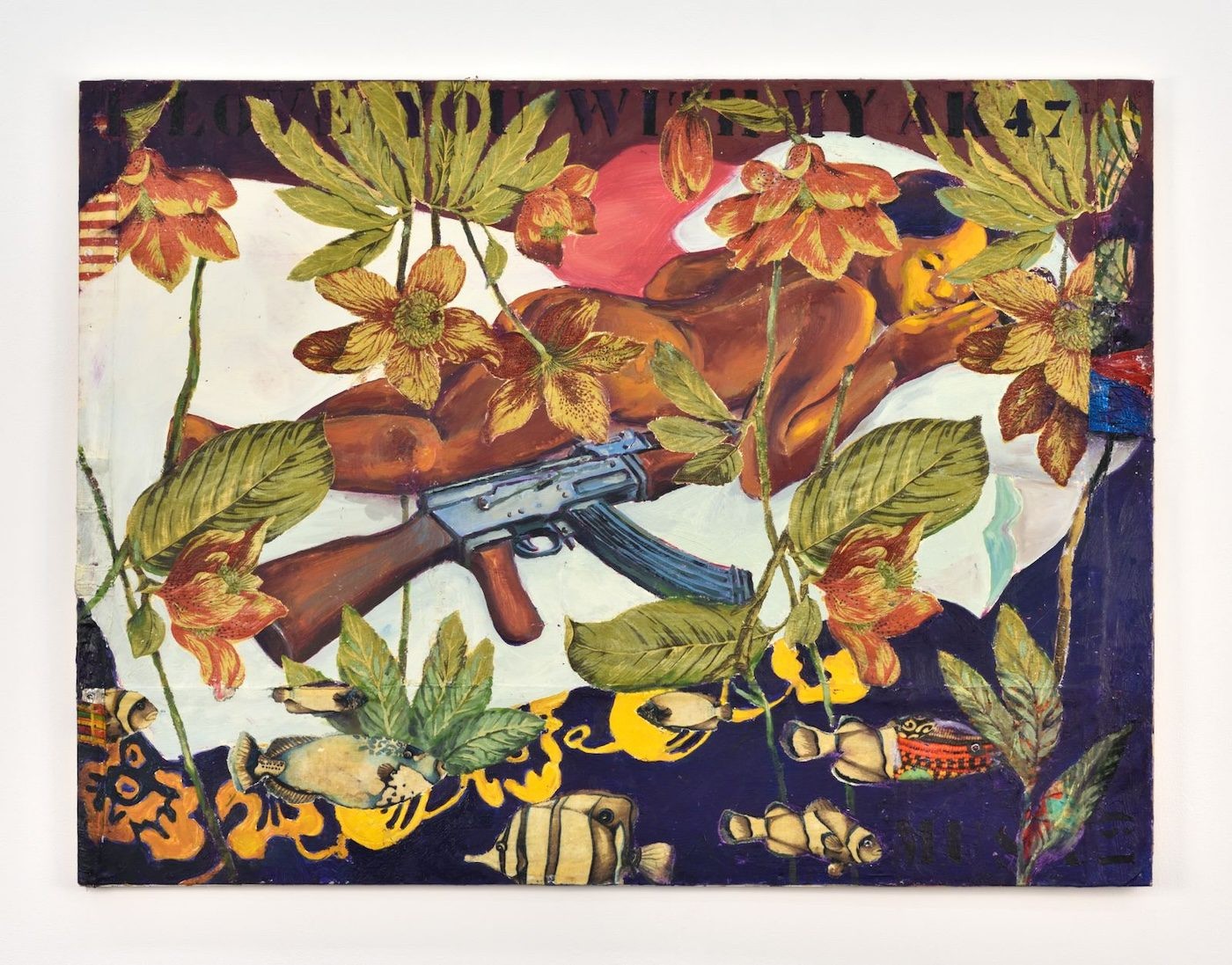

Antilles for the Antilleans: Saltwater clears/clouds the eyes, 2016. Installation at Jamaica Biennale.

C&: Could you give us an idea of what you are contributing to the Dak’Art Biennale 2018?

OR: Antilles for the Antilleans: Saltwater is a multi-paneled textile-based work. It consist of nine panels of printed poly crepe de chine which mimic banners, handkerchiefs, posters, and other objects seen in local Jamaican environments. Four of the panels are printed with lines from my own writing, which presents two conflicting ideas about an element important for the definition of the Caribbean: the saltwater that surrounds the islands. In my work, the sea becomes an element that is both healing as well as disorienting.

Caribbean people have had a fraught relationship with the sea as it historically carried Africans to the islands for exploitation. In modern times it is also the way these island nations earn their money through tourism and the sea also connects them to the rest of the world. Many of the images are remembered from the visual culture of the region. Everything became a jumble of thought, memory, history, and culture. The project was developed from an initial collaboration on Monica Rodriguez’s installation Las Antillas Para Los Antillanos for Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions-Open Air Prisons. Her installation sought to assemble contributions from visual artists, musicians, poets, and writers into an ever-evolving research center which focuses on the Caribbean as a space.

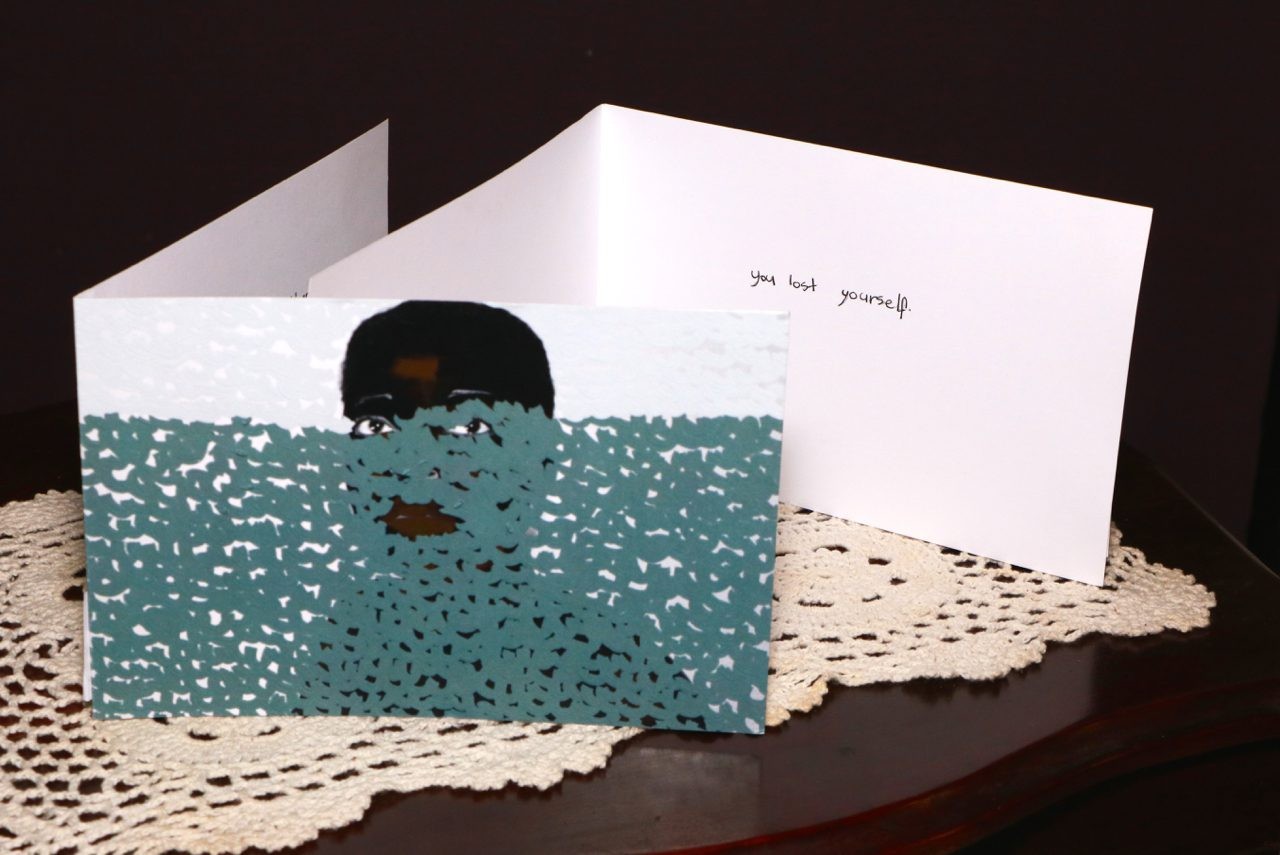

Oneika Russell, Notes To You (detail), 2014. Courtesy the artist.

C&: You were brought up in Jamaica and have spent time on a scholarship in Japan. How would you describe the different art scenes?

OR: That is an interesting comparison to make. Jamaica is in a very different position from Japan in terms of the dimensions I prefer expanse or vastness of a collector market and art landscape. In Jamaica, art is in the way we speak and move, it inhabits a spirit of improvisation and inventiveness. In Japan, art is also embedded in daily life but it is tied to tradition and, in my experience, is often studied and systemized. Jamaican artists often struggle to have the wider populace and state promote and support their work, while in Japan the fine arts are greatly treasured by the populace. There is extensive support by the state for local Japanese artists, with many funded programs, exhibition opportunities, residencies, incubators etc. Within our art scene in Jamaica, there are collectors, curators, and institutions which show support, but there is always need for more initiatives and access for artists to easily enter the scene and have the opportunity to thrive. And whereas Japanese artists seem to absorb the aesthetic of popular and traditional culture in their work, Jamaican contemporary artists often use their work politically to rethink and question ideas about our heritage, national identity, culture, hierarchies, and biased structures in society.

Oneika Russell attended the Edna Manley College in Kingston, Jamaica. from 1999 to 2003 where she completed a diploma in the Painting Department. In 2003 she left for studies at Goldsmiths College in London in the Centre for Cultural Studies. While at Goldsmiths, Oneika began to integrate her deep interest in combining the practice of Painting with New Media. She has also completed the Doctoral Course in Art at Kyoto Seika University, Japan concentrating on Animation in Contemporary Art. She is currently a lecturer across The Fine Art and Visual Communication Departments at The Edna Manley College.

Interview by Theresa Sigmund.

Plus d'articles de