Remembering One of South Africa’s Greatest Photographers

9 Juillet 2018

Magazine C&

8 min de lecture

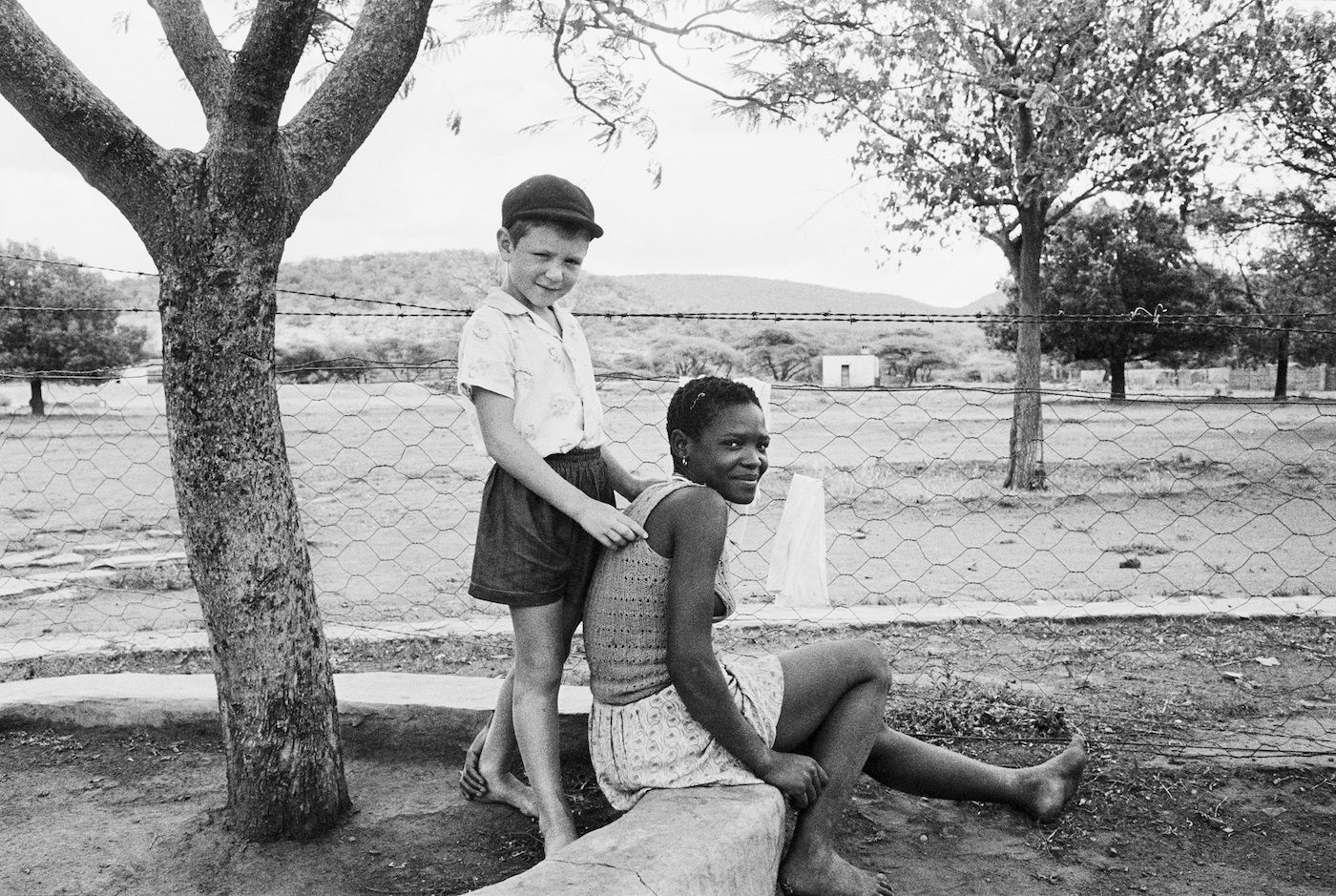

David Goldblatt, who passed away at the end of June, remains one of South Africa’s most important photographers. Sean O’Toole remembers the artist who documented the nuances of everyday life in apartheid South Africa, who was a father figure to Zanele Muholi, and who refused a national honor in support of press freedom.

It was a throwaway statement, a remark made in passing, its disposability nonetheless emblematic of the racially atomized character of South Africa today, nearly a quarter century after the achievement of universal franchise in 1994. Shortly after photographer David Goldblatt’s death, on 25 June from cancer, someone – it is better not to mention who – remarked on the apparent lack of public grieving by Black photographers on social media. Huh! Even if we accept that not everyone grieves in the same way, the statement was patently untrue. Omar Badsha, Tshepo Moloi, Neo Ntsoma, Lindokuhle Sobekwa, and many other photographers posted statements of sorrow and tribute recognizing the loss.

Zanele Muholi’s Instagram post was especially heartfelt. It comprised a film clip and short note. The clip was made in November 2017 when Muholi received the Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters) at the French Embassy in Pretoria, and it shows Goldblatt speaking at the ceremony. He recalls how, after he saw some of Muholi’s student work at the Market Photo Workshop, the Johannesburg photography school he cofounded in 1989, she knocked on the door of his home in Fellside one Saturday morning. It was an unannounced call. “I’m Zanele Muholi and you are going to mentor me,” Goldblatt recalls her saying. “That was the basis of our relationship.”

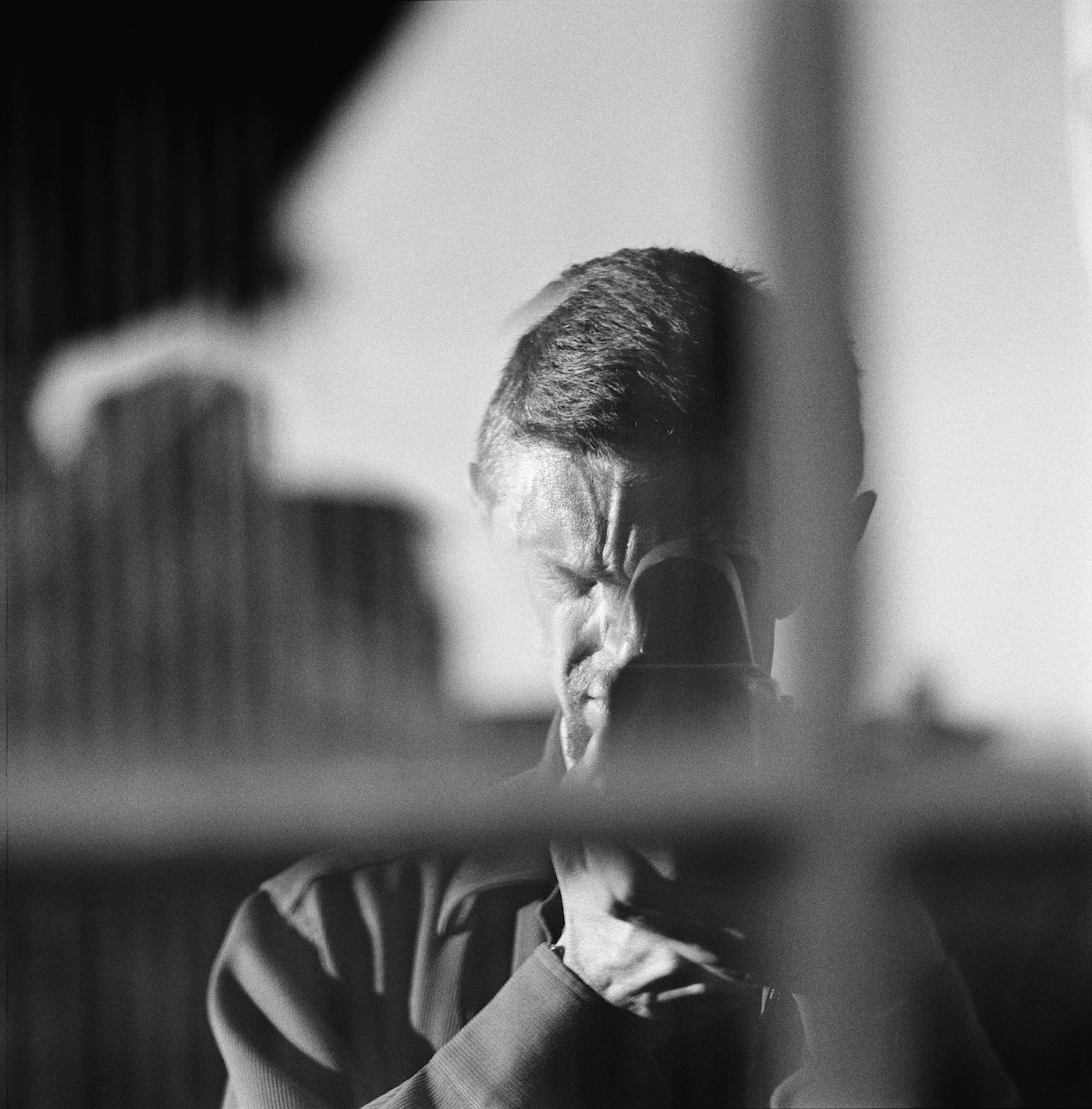

</a> David Goldblatt, Self-portrait at Consolidated Main Reef Mines, Roodepoort. May 1967. Courtesy of Goodman Gallery</figure>

The two photographers developed a profound bond. In 2006 Goldblatt won the Hasselblad Award, which included a cash prize; he gave half of this money to Muholi so she could study for a master’s degree in documentary media at Ryerson University in Canada. In an interview with Muholi last year, we spoke at length about Goldblatt. That he was a straight white man didn’t matter, she said; his “open-mindedness and willingness to listen” inspired her to produce quality work. It wasn’t just his guidance but the methods he adopted in his own photography – “of going back, following up, and revisiting” – that subtly influenced her practice.

Goldblatt’s reputation hinged on his roaming, occasionally lyrical documentary photographs of South African society, but at home his bookshelf included photo books by Bill Brandt and Edward Weston. Along with nude portraitist Sam Haskins, Brandt was an important early influence on Goldblatt, who – like his heroes – also produced his own nudes. Many remain unseen. “He captured the most beautiful portrait of me in the nude,” said Muholi. “It is not known. It is a very beautiful image.” The intimacy required to broker such an exchange speaks to the deeper significance of their relationship. “Some of us grew up without fathers,” said Muholi. “He filled that role, in a way. I could be me, and I had no reservations.”

The death of Goldblatt has meant different things to different people. For obituary writers and their readers he was a moral conscience, someone who witnessed the complicated character of life under the yoke of apartheid with subtlety and empathy. For art historians and their students, he was a modernizing force, someone whose work suggested nuanced ways of seeing and portraying things beyond the immediacy of photojournalism. For photographers like Muholi, Sabelo Mlangeni (whose rent Goldblatt helped cover), and Jo Ractliffe (who he visited in hospital after her back injury and for whom he dedicated a 2015 exhibition), he was something dearer.

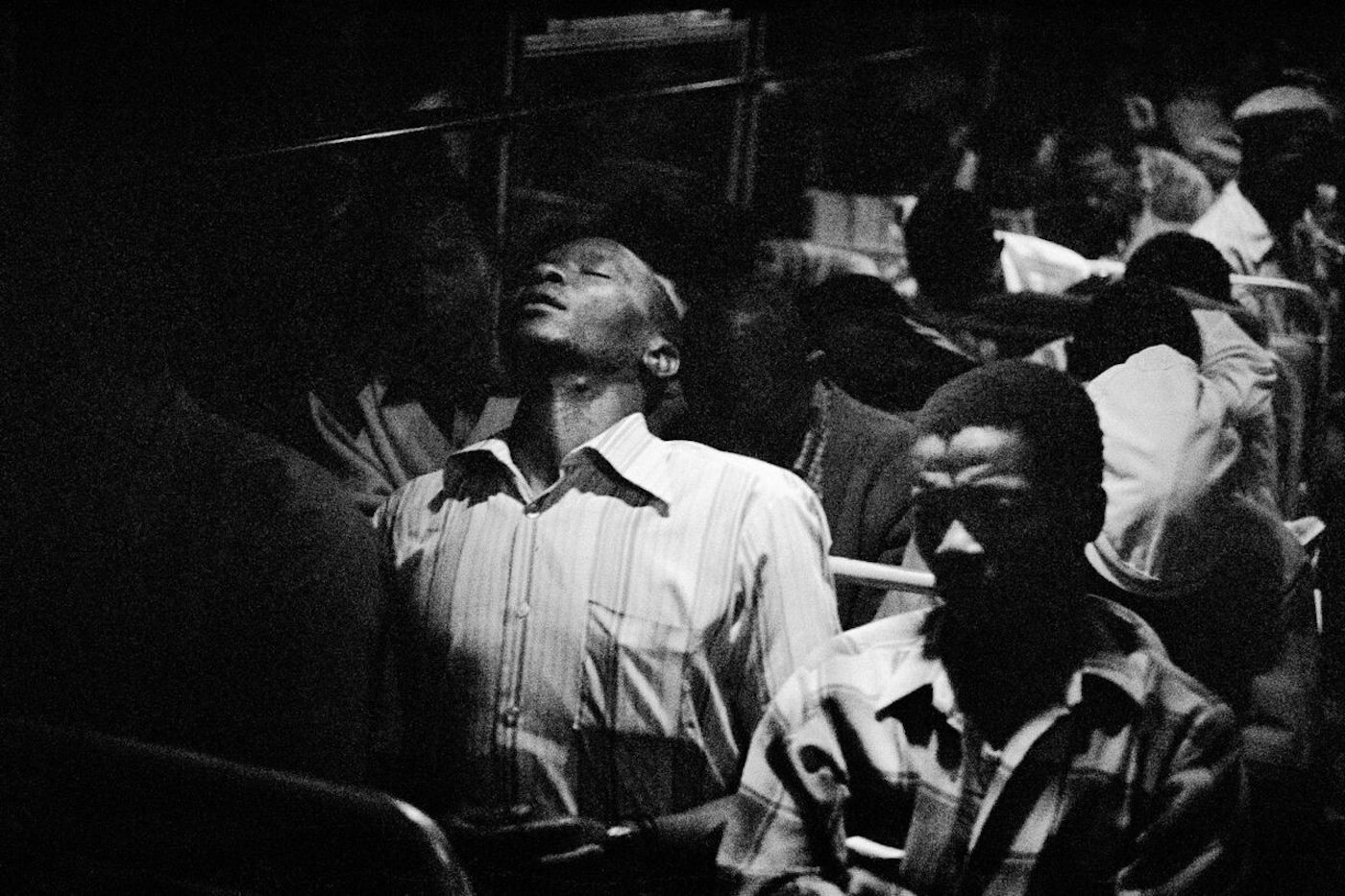

</a> David Goldblatt, Going home: Marabastad-Waterval route: for most of the people in this bus, the cycle will start again tomorrow at between 2 and 3 am, 1984. Courtesy of Goodman Gallery</figure>

Goldblatt also meant something to the Fallists, that insurgent youth brigade spearheading change at South Africa’s universities. In 2016, curator and activist Wandile Kasibe organized Echoing Voices from Within, a photography exhibition at the University of Cape Town (UCT) that commemorated the first year of the student movement. Largely told from a student perspective, the exhibition nonetheless included Goldblatt’s so-so photograph of the 2015 removal of sculptor Marion Walgate’s bronze statue of colonial politician and mining oligarch Cecil John Rhodes at UCT. “As the statue was dethroned,” recalled Goldblatt of this galvanizing event in the life of the student movement, “so 2000 pairs of arms went up like some form of mystical ritual. I was outnumbered and outclassed.”

When Kasibe’s exhibition opened in March 2016, seven members of the Trans Collective – a group of transgender, gender non-conforming, and intersex students initially linked to the Fallist movement – staged a protest in the Centre for African Studies Gallery. Their action included painting slogans onto various photographs. It was the first time in a career going back to 1963 that a photo by Goldblatt had been vandalized. He had in the past been threatened with violence, he told me in 2016, but never censored. Throughout that interview he reiterated his bewilderment at the lack of vigorous public debate, both at the vandalism of the exhibition and the earlier burning of paintings on UCT’s campus in February.

“It is possibly reflective of a wider malaise in the society,” he speculated. When I published an article quoting Goldblatt, voices on social media jibed that vigorous debate was in fact happening, online. “I don’t Facebook, and I don’t tweet, whatever these things are,” Goldblatt noted. He expressed worry about both the retreat of public debate online and the stridency of “direct action” by student activists, which he likened to the civil unrest of the 1980s, a situation as much as a subject that forms a notable lacuna in his seemingly omniscient archive.

Goldblatt’s disgust with UCT’s handling of the student movement’s demands, which later extended to covering up and/or removing objectionable art displayed on campus, eventually prompted him to withdraw his archive and sign it over to Yale University in the United States. “I find it very sad that this has happened,” he told me last year. “I suppose I am being overdramatic.” He nonetheless insisted that censorship “is the kiss of death.” It was this article of faith that in 2011 saw him reject the Order of Ikhamanga, a presidential honor, in protest at a work-in-progress piece of legislation aimed at restricting press freedom. A year later he was one of four people who, in a show of solidarity for artist Brett Murray, met protestors outside the Goodman Gallery, then at the center of a political firestorm following the exhibition of Murray’s controversial painting of President Jacob Zuma with his penis exposed.

David Goldblatt, Anna Boois, goat Farmer, with her birthday cake and vegetable garden, Kamiesberge, near Garies, Namaqualand, Northern Cape, 20 September 2003. Courtesy of Goodman Gallery Goldblatt’s principled stands were grounded in a particular worldview. “I was a liberal and I have never made a secret of it,” he said in 2010. During the apartheid years, this meant he did not support the cultural boycott of South Africa. He also accepted state and mining-house commissions (“I always felt that living in South Africa, simply by living here, breathing the air, you compromised yourself; you were complicit in the system, whether you were black or white, unless you were prepared to go to jail and if necessary be hanged for it … After that you had to accept that we were all shades of grey and you had to make decisions about where you stood in relation to particulars,” he said in 2010). The meaning of Goldblatt is a work in progress, which, on balance, is a good thing. People die but the significance of their actions can – sometimes, not always – make us reconsider where we are, and how we got here. Goldblatt’s work has that capacity. Four years ago, shortly after seeing Okwui Enwezor’s Rise and Fall of Apartheid exhibition in Johannesburg, I contacted Santu Mofokeng, then on the cusp of being seized by the awful disease that has rendered him literally speechless and wheelchair-bound. We spoke about three unavoidable figures in Enwezor’s exhibition: Goldblatt, Peter Magubane, and Jürgen Schadeberg. Mofokeng described Magubane as having “made photography a respectable occupation” for young Black photographers, Schadeberg as his “mentor,” and Goldblatt as “an inspiration.” The history of South African photography is a mosaic of possibilities. Goldblatt’s work is a defining contribution. Its significance overwhelmingly resides in what it portrays – a fractured people and their landscapes – but its fullness stems from what it suggested and provoked, of course in audiences, but also among younger photographers making their way in the world. Recalling his younger self, sitting on a Soweto train in 1980s South Africa, Mofokeng said: “It dawned on me that if Goldblatt and Schadeberg made sense then, despite working in different and disparate styles, surely there is a road in the middle for me.” It is mark of Goldblatt’s efforts that his legacy is entangled in the life and work of other great photographers, some who wept very publically at his death, others who have long recognized and praised his achievements. Sean O’Toole is a writer and co-editor ofCityScapes, a critical journal for urban enquiry. He lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

de

En Conversation

Fantômes et images en mouvement : le Black Atlas d’Edward George

On Exile, Amulets and Circadian Rhythms: Practising Data Healing across Timezones

« Considérer le processus avec soin et intentionnalité » : Favour Ritaro perpétue des legs essentiels en matière de commissariat d’exposition

de

Mentorship

Rwanda’s Creative Sector Holds Vast Potential Through Women Artists

Terra Foundation for American Art funds C& Critical Writing Workshops and C& Mentoring Program in 2023