We are still stumbling across curated incredibilities taking place in museums and art spaces which make us realise: we are absolutely not there yet.

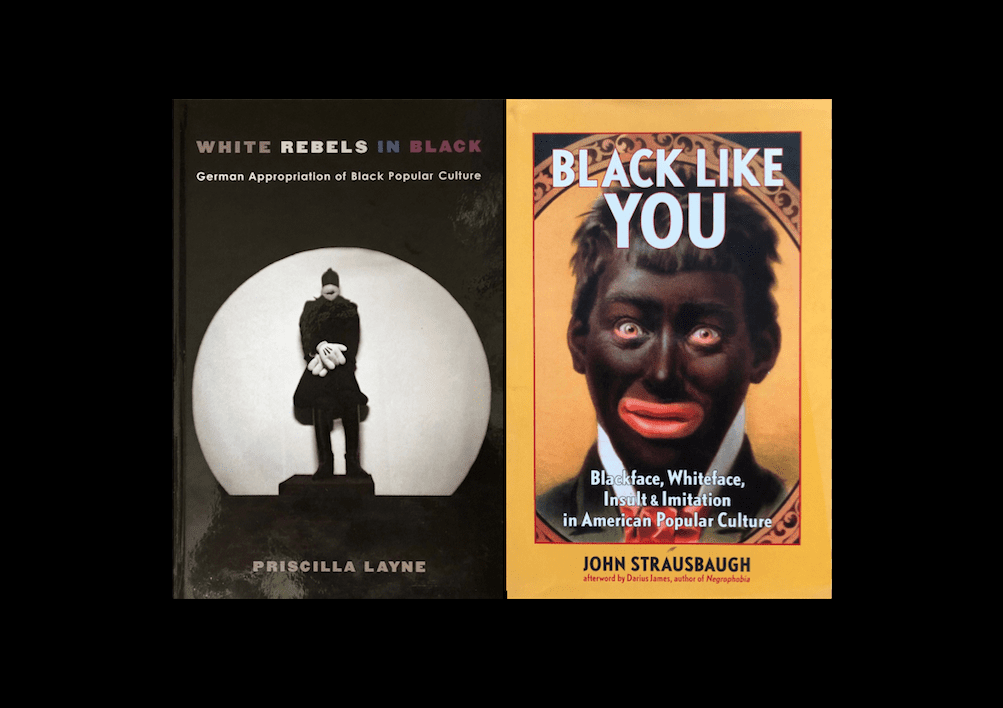

Covers from books "White Rebels in Black" and "Black Like You"

.

Smile: to grin with closed lips, the corners of the mouth turned up, expressing satisfaction, amusement. This is the response the Museum for Communication Frankfurt is currently hoping to elicit from visitors when they see a video work by the artist Murray Gaylard. It shows Gaylard, a white South African who studied art at the Frankfurt Städelschule, wearing a dark curly wig and black hand puppets. He and the puppets are exaltedly lip-synching to the 1980s song “Making Love out of Nothing at All” by the Australian soft rock band Air Supply. Even visitors who don’t know the stereotypical golliwog dolls must have the unpleasant sense that this scenario, complete with Afro wig and hand puppets, clearly plays with the stereotypical, racist image of “blackface”. A minstrel show in the 21st century.

There are countless artists. Also numerous collectors and galleries that are into bad art. That Gaylard in this work is knee-deep in perpetuating racist images of Black people (one of those non-Black artists who may feel they are acting on behalf of the Black oppressed) is one thing. However, the fact that a large, publicly sponsored house like the Museum for Communication is prominently featuring this 2009 work as part of the exhibition “Nam June Paik and contemporary media Art from the collection from Kelterborn” is not simply problematic, but plainly racist. However, it is actually the description on the wall that makes you truly speechless. For the sake of documenting the incredibility, we want to reproduce it entirely here:

“A young man steps in front of a camera and begins lip-synching to a song. He moves dancing to the rhythm of the music and with the refrain holds up two hand puppets, forming a singing trio with them. Long before the mass distribution of TikTok, Gaylard dubbed a kitschy song, the video makes us laugh. But also lets us smile, because the artist wears a black wig and the hand puppets are designed after dark-skinned people. The recording is named after his best friend Romano.”

The video makes us laugh. But also lets us smile, because the artist wears a black wig and the hand puppets are designed after dark-skinned people. Back to the definition of smiling: to grin with closed lips, the corners of the mouth turned up, expressing satisfaction, amusement. So, according to the museum, it seems to be great fun to see how racist stereotypes of Black people are celebrated and cemented here.

Viewers in front of Murray Gaylard’s work (right) at the Museum für Kommunikation Frankfurt. Copyright: Museum for Communication Frankfurt

So we are still living in an age in which the ever so politically correct contemporary art scene either depicts Black people in racist ways and/or completely excludes them as protagonists. The latter happened only recently in the exhibition “Milchstraßenverkehrsordnung” at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. Is and was there nobody (?!) who during the conceptualization of the exhibition even briefly wondered whether the concept actually made sense – namely inviting 21 white and one Asian artist to a project that from a curatorial perspective clearly had Afrofuturism in mind? After the collective Soup du Jour and others had massively criticized the show, eventually a (purely male) panel discussion was organized at the venue. The panelists with diasporic perspectives had to once again explain that the concept of “working as equals” was of course lovely, but not possible as long as we were living in a world where oppression and racism still prevail.

It is an exciting time right now. Things are in motion. Structures formerly regarded as « fixed » are beginning to waver. What is actually comforting about the situations currently still happening (art fairs that do not communicate any sort of diversity, galleries that exhibit 80% male and white artists, museums that unreflectedly exhibit discriminatory content) is that nowadays nothing goes unnoticed. The case of Künstlerhaus Bethanien even wound up in the British Guardian. An institution can hardly commit a bad faux pas without there being an echo of the first detonations after a few days at the latest via networks in Accra, New York or Dortmund. One critic recently wrote that hate-filled vigorous debates on the web often had the effect of a tea light on a windowsill as soon as they were moved from the web into real life on podiums or in public discussions. “No one knows exactly what the whole fuss was actually all about.” Well, without the fuss, a work like Murray Gaylard’s would perhaps be featured without comment or context in a medium-sized museum in a medium-sized German city until the bitter end of the exhibition, inviting people to have a good laugh at racist hand puppets.

Educational institutions such as museums, however, have both a moral and an ethical responsibility to create a cultural foundation for the security, freedom of expression and visibility of minorities in a German majority society and to challenge the often white, capitalist, mainstream and heteronormative cultural landscape in Germany in general. It is crucial because these are still often places that embody little diversity in terms of class, race and gender. This is a very political concern, as the results of the German federal election in 2017, in which 12.6% of German voters cast their vote for the AfD, clearly point to the general increase in right-wing populism in Germany and Europe. The argumentation of the right always remains the same: instrumentalizing cultural institutions by identifying them as symbols of failed integration and radical left-wing propaganda in Germany. It is precisely for this reason that public institutions must set an example for an intercultural, open Germany that can be home to a wide variety of people, backgrounds and worldviews, and whose programs and events counter stereotypes regarding minorities living in Germany rather than perpetuating them as the Museum for Communication has done.

In the meantime the museum has changed the wall text, which however does not reflect on the racist connotation of the work by Murray Gaylard, but instead outlines a statement by the artist about his work.

More Editorial